A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Sunday, June 18, 2017

Helmut Kohl: leader who united Europe as well as Germany

When East Germany collapsed, the West German chancellor rose to the occasion and helped heal the cold war’s bitter divisions

Mikhail Gorbachev, leader of the USSR, and Helmut Kohl exchanging pens after signing a treaty in Bonn.

Photograph: Michael Urban/Reuters

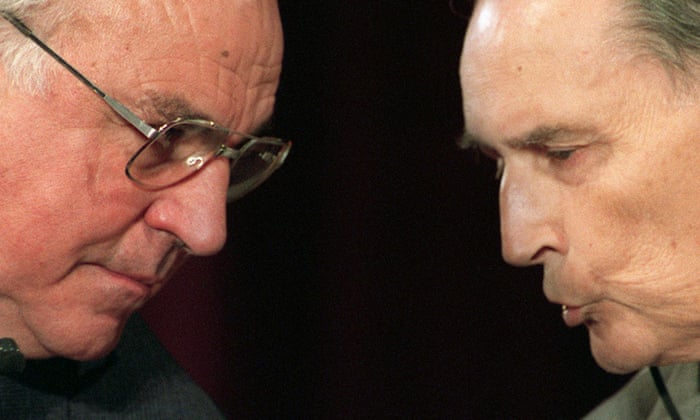

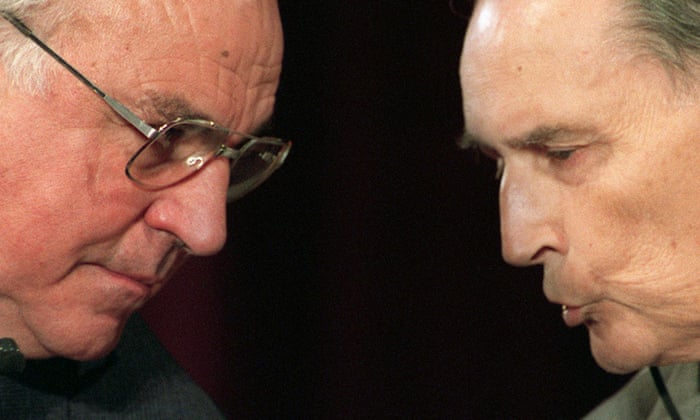

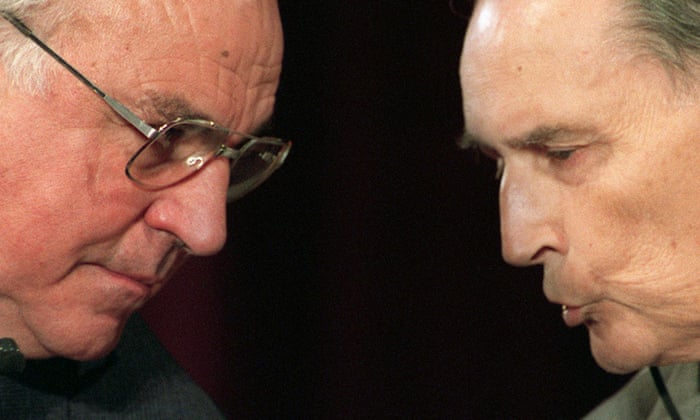

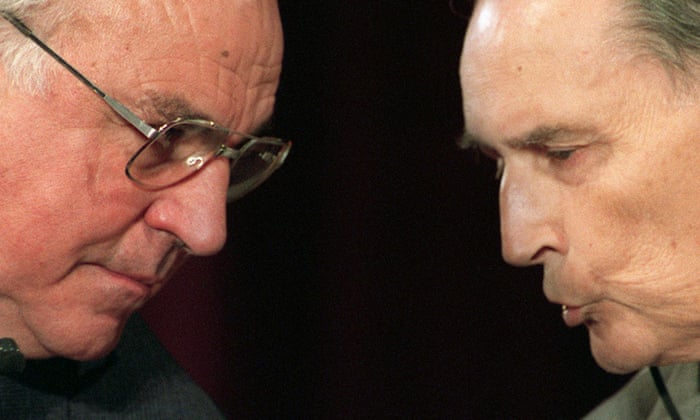

Helmut Kohl and the French president, François Mitterrand in 1993. Photograph: Gerard Fouet/EPA

Simon Tisdall-Saturday 17 June 2017

Simon Tisdall-Saturday 17 June 2017

Helmut Kohl, who died on Friday aged 87, was one of a trio of dominant western conservative politicians – along with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher – whose determined ideological and practical opposition to the Soviet Union helped lead in the closing months of 1989 to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent end of the cold war that had gripped Europe since 1945.

But despite his reputation as a hardliner and his achievement as Germany’s longest-serving chancellor since Bismarck, Kohl in person was a shambling bear of a man (he was 193cm or 6’4” tall) who often did not take himself too seriously. Rather than claim a perspicacity he did not possess, Kohl freely admitted later that he did not foresee the sudden Soviet implosion and was as surprised as anyone when it happened.

The days when Europe was divided between east and west are hard to picture now. But a visitor to West Berlin in December 1988 was confronted by a grim reality that owed nothing to Hollywood movies or John Le Carré spy novels: watchtowers manned by armed East German border guards, snow falling on barbed-wire coils suspended over the river Spree, the forbidding no-man’s land of Checkpoint Charlie, and the burned-out Reichstag building silhouetted against an icy black sky.

A few kilometres down the road, on an evening just before Christmas that year, Kohl was to be found in a bar-restaurant near the Kempinski hotel on the Kurfürstendamm, mixing gaily with the crowd of drinkers without need of minders or aides. Kohl did not want to talk about politics that night. He appeared oblivious to any thought of the seismic changes that were about to shake Europe. But he was happy to share generous amounts of his favourite tipple, sweet riesling wine from Rhineland-Palatinate where he had formerly served as minister-president.

It is difficult to imagine Angela Merkel, Kohl’s protege and now chancellor herself, behaving so artlessly in public. Unprepared though he might have been, Kohl rose to the occasion presented by East Germany’s collapse with a purposeful single-mindedness that shocked and alarmed many in the west, not least Margaret Thatcher.

Kohl took literally theinjunction in the West German constitution to restore the country’s unity. He produced his own unilateral 10-point plan for “Overcoming the Division of Germany and Europe” without reference to the western wartime powers – the US, Britain and France. In a series of bold and rapid moves in 1990, he travelled to Moscow to seek President Mikhail Gorbachev’s acquiescence in German reunification, signed a fast-track economic and social union treaty with the East German leaders who had ousted Erich Honecker’s Communists, and with the help of his able foreign minister, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, won the backing of the US.

Kohl had luck on his side, too. In part his success was rooted in Ostpolitik (“east policy”) pursued by the former Social Democrat (SPD) chancellors Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt. Their policy of détente towards the Communist-controlled East had been steadfastly opposed by Kohl’s Christian Democrats (CDU) and the hard right. But in the end, Kohl’s breakthrough vindicated that policy.

For her part, Thatcher remained opposed to reunification throughout, fearing that a resurgent, reviving Germany would once again dominate Europe. She was comprehensively out-manoeuvred by Kohl. But 25 years later, it could be said that Thatcher’s premonition has proved accurate. The Greek government would certainly agree. Reunification, ratified in September 1990, turned out to be an enormously costly business for both Germanys. The eastern states were poor, persecuted and polluted, while the taxes levied in western Germany to pay for the project, and accompanying westwards migration of jobless Ossis (East Germans), caused deep resentment in some sections of German society.

The fact that Germany has ultimately proved able to afford this epic act of national reconstruction is attributable, in part at least, to Kohl’s other signal political achievement: the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 that brought the European Union into existence and paved the way for the creation of the euro currency. Whatever else they may have done, the EU and the euro (replacing the former, less politically integrated European Economic Community) gave Germany the markets and the means to produce a second German industrial and manufacturing miracle.

In this ambitious vision for a united Europe, Kohl found a willing partner not on the political right but in the rotund form of François Mitterrand, France’s Socialist president. Both men remembered the bad old times. Both reasoned that Europe would only be safe and secure if its two leading powers and its most frequent antagonists, France and Germany, worked in tandem. For Kohl, such cooperation was at one with his instinct for peaceful reconciliation. Early in his second term as chancellor, in 1984, he shook hands with Mitterrand on the first world war battlefield at Verdun, as if to finally bring down the curtain on two world wars.

In the same year he became the first German leader to address the Knesset in Israel. At the same time, he was not afraid to confront strength with strength, in facing down the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union. West Germany played a full part in the controversial 1980s US deployment of intermediate-range cruise and Pershing nuclear-tipped missiles in Europe, under the banner of Nato, the target of the Greenham Common protests in Britain.

And it was Kohl who was happy to play host to Reagan, the hawkish US leader, and sit with him on a platform near the Brandenburg Gate in divided Berlin in 1987 when Reagan issued his challenge: “Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Kohl served as chancellor continuously from 1982 to 1998. He retired

from public life in 2002. His later years were marred by a scandal over

CDU party financing and the suicide, in 2001, of his popular wife, Hannelore.

Until he suffered the first of a series of serious illnesses, he

continued to air his views, and was sharply critical of Merkel’s

pro-austerity policies in response to the global financial crisis.

Kohl’s verdict was terse: “Die macht mir mein Europa kaputt” (“She’s destroying the Europe I built.”)

Mikhail Gorbachev, leader of the USSR, and Helmut Kohl exchanging pens after signing a treaty in Bonn.

Photograph: Michael Urban/Reuters

Helmut Kohl and the French president, François Mitterrand in 1993. Photograph: Gerard Fouet/EPA

Simon Tisdall-Saturday 17 June 2017

Simon Tisdall-Saturday 17 June 2017Helmut Kohl, who died on Friday aged 87, was one of a trio of dominant western conservative politicians – along with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher – whose determined ideological and practical opposition to the Soviet Union helped lead in the closing months of 1989 to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent end of the cold war that had gripped Europe since 1945.

But despite his reputation as a hardliner and his achievement as Germany’s longest-serving chancellor since Bismarck, Kohl in person was a shambling bear of a man (he was 193cm or 6’4” tall) who often did not take himself too seriously. Rather than claim a perspicacity he did not possess, Kohl freely admitted later that he did not foresee the sudden Soviet implosion and was as surprised as anyone when it happened.

The days when Europe was divided between east and west are hard to picture now. But a visitor to West Berlin in December 1988 was confronted by a grim reality that owed nothing to Hollywood movies or John Le Carré spy novels: watchtowers manned by armed East German border guards, snow falling on barbed-wire coils suspended over the river Spree, the forbidding no-man’s land of Checkpoint Charlie, and the burned-out Reichstag building silhouetted against an icy black sky.

A few kilometres down the road, on an evening just before Christmas that year, Kohl was to be found in a bar-restaurant near the Kempinski hotel on the Kurfürstendamm, mixing gaily with the crowd of drinkers without need of minders or aides. Kohl did not want to talk about politics that night. He appeared oblivious to any thought of the seismic changes that were about to shake Europe. But he was happy to share generous amounts of his favourite tipple, sweet riesling wine from Rhineland-Palatinate where he had formerly served as minister-president.

It is difficult to imagine Angela Merkel, Kohl’s protege and now chancellor herself, behaving so artlessly in public. Unprepared though he might have been, Kohl rose to the occasion presented by East Germany’s collapse with a purposeful single-mindedness that shocked and alarmed many in the west, not least Margaret Thatcher.

Kohl took literally theinjunction in the West German constitution to restore the country’s unity. He produced his own unilateral 10-point plan for “Overcoming the Division of Germany and Europe” without reference to the western wartime powers – the US, Britain and France. In a series of bold and rapid moves in 1990, he travelled to Moscow to seek President Mikhail Gorbachev’s acquiescence in German reunification, signed a fast-track economic and social union treaty with the East German leaders who had ousted Erich Honecker’s Communists, and with the help of his able foreign minister, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, won the backing of the US.

Kohl had luck on his side, too. In part his success was rooted in Ostpolitik (“east policy”) pursued by the former Social Democrat (SPD) chancellors Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt. Their policy of détente towards the Communist-controlled East had been steadfastly opposed by Kohl’s Christian Democrats (CDU) and the hard right. But in the end, Kohl’s breakthrough vindicated that policy.

For her part, Thatcher remained opposed to reunification throughout, fearing that a resurgent, reviving Germany would once again dominate Europe. She was comprehensively out-manoeuvred by Kohl. But 25 years later, it could be said that Thatcher’s premonition has proved accurate. The Greek government would certainly agree. Reunification, ratified in September 1990, turned out to be an enormously costly business for both Germanys. The eastern states were poor, persecuted and polluted, while the taxes levied in western Germany to pay for the project, and accompanying westwards migration of jobless Ossis (East Germans), caused deep resentment in some sections of German society.

The fact that Germany has ultimately proved able to afford this epic act of national reconstruction is attributable, in part at least, to Kohl’s other signal political achievement: the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 that brought the European Union into existence and paved the way for the creation of the euro currency. Whatever else they may have done, the EU and the euro (replacing the former, less politically integrated European Economic Community) gave Germany the markets and the means to produce a second German industrial and manufacturing miracle.

In this ambitious vision for a united Europe, Kohl found a willing partner not on the political right but in the rotund form of François Mitterrand, France’s Socialist president. Both men remembered the bad old times. Both reasoned that Europe would only be safe and secure if its two leading powers and its most frequent antagonists, France and Germany, worked in tandem. For Kohl, such cooperation was at one with his instinct for peaceful reconciliation. Early in his second term as chancellor, in 1984, he shook hands with Mitterrand on the first world war battlefield at Verdun, as if to finally bring down the curtain on two world wars.

In the same year he became the first German leader to address the Knesset in Israel. At the same time, he was not afraid to confront strength with strength, in facing down the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union. West Germany played a full part in the controversial 1980s US deployment of intermediate-range cruise and Pershing nuclear-tipped missiles in Europe, under the banner of Nato, the target of the Greenham Common protests in Britain.

And it was Kohl who was happy to play host to Reagan, the hawkish US leader, and sit with him on a platform near the Brandenburg Gate in divided Berlin in 1987 when Reagan issued his challenge: “Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”