A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Sunday, July 8, 2018

Indo-Pacific Command a threat to peace in Indian Ocean

2018-07-06

On May 31st this year, at a solemn ceremony in Hawaii, the United States

military renamed its Pacific Command as the “Indo-Pacific Command”. The

move, though significant in many respects, has not generated as much

debate as it should have in the South Asian region.

In

a tweet to mark the occasion, the US embassy in New Delhi said: “In

symbolic nod to India, United States renamed its @PacificCommand the

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. Looking forward to higher levels of

#USIndiaDefence cooperation.”

In

a tweet to mark the occasion, the US embassy in New Delhi said: “In

symbolic nod to India, United States renamed its @PacificCommand the

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. Looking forward to higher levels of

#USIndiaDefence cooperation.”This week, testifying before the United States Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Alaina Teplitz, the ambassador-nominee for Sri Lanka and the Maldives, said the two island nations were important for the wider security and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific region.

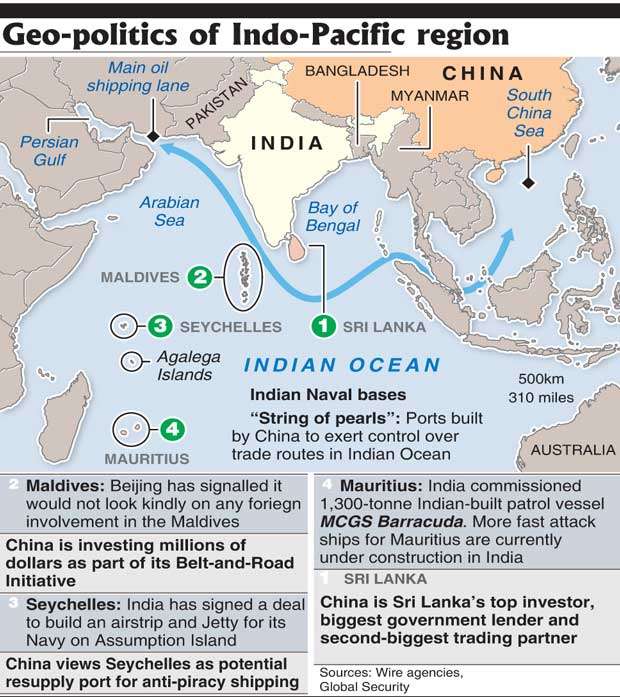

She noted that both Sri Lanka and the Maldives are positioned astride key shipping lanes that connect the Straits of Hormuz and Malacca, the free navigation of which is vital to US economic and security interests. Teplitz said Washington must also be mindful of the economic and commercial opportunities each country afforded, and the importance of working with them to maintain a rules-based international order.

The mentioning of the Indo-Pacific region in her testimony was deliberate. It was an attempt to further popularize or formalise the term ‘Indo-Pacific’, while her call for a rules-based international order is a direct swipe at China, which is being accused by the US and its Asian allies of wrongfully claiming sovereignty over disputed islands in the South China Sea and of building artificial islands for military use in violation of international law.

The Donald Trump administration, which is seen to be opposing everything

that was Barack Obama, has fully embraced the term Indo-Pacific, which

the Obama administration showed some reluctance to formalise.

After a meeting between India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Trump in the White House in June last year, a joint communiqué described the two leaders as “stewards” for the peace and stability of the Indo-Pacific region. During Trump’s East Asia tour in November last year, the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ figured so liberally in statements that it exposed hurried and deliberate efforts to win recognition for the new region. That the term is also being liberally used in political discourses in Japan is no coincidence. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is a key architect of the concept.

Last month, addressing the Shangri La Dialogue conference in Singapore, Modi defined the Indo-Pacific region as “a natural region” that stretches from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of America. While emphasising that India’s acceptance of the Indo-Pacific region was not directed against any nation, he said the building of a “stable, secure and prosperous Indo-Pacific region” was an “important pillar” of India’s partnership with the US.

With the formal announcement of the Indo-Pacific command, the Indian Ocean region is set to become a militarised zone where the big powers will flex their military muscles sooner than later. The new command together with the US Central Command (for Middle East), the African Command and the European Command provides around-the-world connectivity to the US military.

The Indo-Pacific Command is a blow to the Indian Ocean peace zone concept. In the 1970s, Sri Lanka had been in the forefront of global efforts to declare the Indian Ocean as a peace zone and had opposed superpower military presence in the region. Although the Soviet Union was supportive of the Sri Lankan initiative, the US, which had a major military base in the Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia, ignored Colombo’s call, which was then fully backed by the Non-Aligned Movement.

It is significant to note that India has veered away from its ‘middle-path’ foreign policy and has cooperated with the US in the renaming of the Pacific Command, in keeping with its redefined geostrategic objective of containing a rising China, with whom it has several territorial disputes, the latest being last year’s Doklam crisis on the Bhutan border. India’s new policy is a major shift from its Indira doctrine which was designed to keep the US out of the seas surrounding India. In keeping with the doctrine – named after Prime Minister Indira Gandhi – India policed and dominated the South Asian part of the Indian Ocean. Now a combined Indo-US effort will go into the policing of this part of Indian Ocean, where concerns have been raised by India over China’s increasing naval movements including the sighting of nuclear submarines.

The move further consolidates the US strategy of making India the lynchpin in containing China – and India, it appears, cherishes the importance the US gives it. India is now, to all intents and purposes, part of the United States’ Asia Nexus. The partnership takes their defence ties to the next level, two years after they signed a logistics defence pact to allow the militaries of both countries to use each other’s assets and bases for repair and replenishment of supplies.

Besides, India is a key member of a tri-nation defence arrangement, also involving the US and Japan. The three countries conduct annual military exercises on a mega scale. Called ‘Malabar’, this year’s exercise, which took place, significantly, a week after the ‘Indo-Pacific Command’ renaming ceremony, was held in the seas off the Pacific Island of Guam where the US maintains its biggest offshore military base. Also part of this arrangement was Australia. However, of late, Canberra has scaled down its involvement, perhaps in deference to its growing trade and investment ties with China.

In international relations, alliances are important because power is also assessed on the basis of the military alliances a nation makes. However much China catches up with the US in terms of economic power, military parity and advancement in science and technology, it still lags behind in making military alliances with strategically important nations. This is why it remains edged out in the contest for the Indo-Pacific region. Despite growing economic ties with China, most ASEAN countries view China with suspicion and will not abandon the US military protection.

The only South Asian country which China can consider as a strategic ally is Pakistan, although Islamabad also maintains close military relations with Washington. Countries like Sri Lanka, Nepal and the Maldives in South Asia, on the one hand, are much in need of China’s development aid and investments, and, on the other, are wary of getting caught in the cold war between China and the Indo-US military alliance. It is diplomatic tightrope walking for these countries. China sees the formalisation of the Indo-Pacific Command as part of the US strategy to instigate China and India into a long-term conflict. The Global Times, China’s official English language mouthpiece, sees India as having fallen into a US trap aimed at strengthening Washington’s control of the Indian Ocean.

The Indo-Pacific military command appears to be bellicose and therefore Indian Ocean nations should be wary of the consequences. The Indian Ocean littoral states – members of the Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Cooperation – need to meet soon to discuss moves to stop the militarisation of the Indian Ocean. India owes these nations a commitment that it will not allow its Indo-Pacific partnership with the US to threaten the peace of the Indian Ocean.