A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Tuesday, March 7, 2017

Precision medicine the theme at world's biggest cancer conference

New era of targeted treatment that will extend survival rates detailed at American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting

Advances

in genetic profiling will allow for cancer treatments that extend

survival while reducing toxic side effects. Photograph: Alamy

A new era of cancer treatment is beginning in which patients get drugs

matched specifically to their tumour, according to scientists at the

world’s biggest cancer conference in Chicago.

Precision or personalised medicine, as it is called, “is about targeting

treatment so that it’s more powerful, while reducing the toxicity, so

there are fewer side-effects”, said Prof Roy Herbst, chief of medical

oncology at Yale Cancer Center. “At the moment it’s more like using a cannonball to kill an ant – and creating a whole lot of damage at the same time.”

The talk at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (Asco)

annual meeting this weekend is of longer survival and fewer toxic

effects through this approach, which is being made possible by advances

in genetic profiling of the tumour itself.

A number of studies will present results at Asco showing that this

approach can extend survival in many different cancer types, while a

study being launched in the UK – if all goes as experts hope – could

result in up to 7,000 women being spared the toxic side-effects of

chemotherapy, while saving the NHS an estimated £17m.

The UK trial, called Optima,

is being run by University College London and Cambridge University and

funded by Cancer Research UK. Beginning in the summer, it will recruit

4,500 women with breast cancer, whose tumours will be genetically tested

as soon as they are diagnosed to establish which will respond to

chemotherapy and which will not.

“It will be a significant step forward,” said Dr Robert Stein, a

consultant in breast cancer at UCL. “In every area of cancer treatment

we have largely functioned on a one-size-fits-all basis because we

didn’t have tools to do any better.”

Of the 50,000 or so women diagnosed with breast cancer in the UK each

year, about 40%, or 20,000, are currently given chemotherapy but only

half of them do well as a result of it; in the other half, the benefit

is unclear. The researchers hope to find out which of the latter group

actually need chemotherapy.

“We would expect to reduce chemotherapy within the trial population by

about two-thirds,” said Stein. “We are looking at between 5,500 and

7,000 fewer a year being treated with chemotherapy than are currently

treated. It’s quite a big deal.”

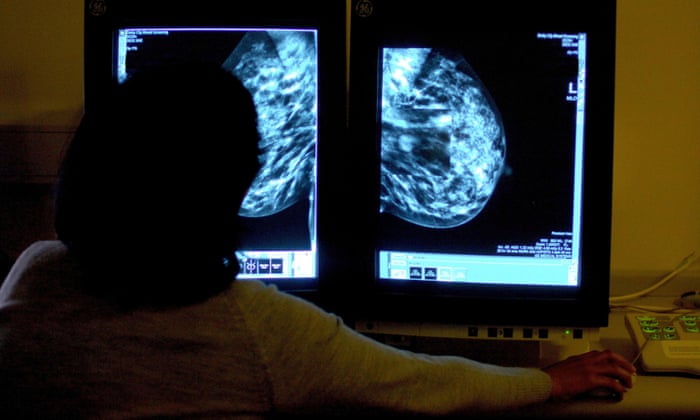

A

trial run by University College London will genetically test 4,500

women with breast cancer to determine if they will respond to

chemotherapy Photograph: Rui Vieira/PA

The downside of chemotherapy is serious. “There are a small proportion

of women who die from treatment. I normally quote 1%,” said Stein.

People can be off work for six months to one year and some never recover

emotionally, he said.

Precision medicine, one of the main themes at Asco this year, was

described by Herbst as “about finding the right key for the lock –

finding out what it is that is driving the tumour, what makes it tick.

At the moment it is informed guesswork, so that treatment often doesn’t

work for large numbers of patients.

“In some ways it is simple – it means that you can make sure you are

giving the right drug to the right person at the right time. In others

it is very complex, because there are so many pieces to the jigsaw. We

need to put the puzzle together.”

The future is already here, said Herbst. Patients who are given the more

established “targeted therapies”, the best known of which is Herceptin,

are already tested to ensure they are among the group in the population

whose tumour has a particular genetic variation.

Herceptin works only for the 20-25% of women whose breast cancer is Her2

positive – it has too much of a protein called human epidermal growth

factor receptor 2, which makes the tumour grow.

About half of melanomas have a mutation in a gene called BRAF. Drugs

targeting BRAF have had some spectacular, if sometimes short-lived,

results but can be dangerous in people whose tumours do not have the

mutation.

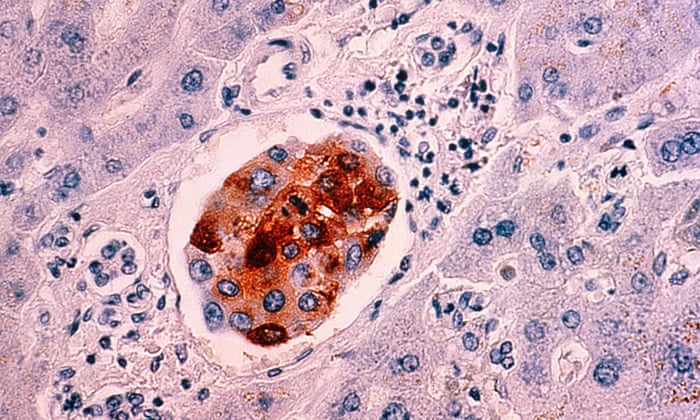

Cancer

patients who are given targeted therapies such as Herceptin are tested

to ensure their tumour has a particular genetic variation. Photograph:

Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images

Instead of these single tests to match a patient with a specific drug,

many experts want to see genetic profiling of all tumours, in the hope

that they can design a package of treatment to suit the individual. But

cost is an issue.

“I think in five years’ time we will be profiling most patients,” said

Herbst, who is leading a trial on personalised medicine in 800 patients

with advanced squamous cell lung cancer called the Lung Cancer Master

Protocol (Lung-MAP) and is an honorary professor at UCL. “The

difficulty is resources – this is $4,000 to $5,000 per test,” he said.

“I think they [the NHS] need to find a way to fund it.”

Genetic testing can be used to select the patients who will best respond

even in early clinical trials of new drugs, a study presented at Asco

has found. These trials are mainly intended to establish whether the

drug is safe, but the study of more than 13,000 patients in 346 trials

found that patients had significantly better outcomes where genetic

profiling took place.

In trials using precision medicine, tumour shrinkage rates were 30.6% compared with only 4.9% in those that did not.

Maria Schwaederle, of the Center for Personalized Cancer Therapy at the

University of California San Diego school of medicine, said: “Our study

suggests that, with a precision medicine approach, we can use a

patient’s individual tumour biomarkers to determine whether they are

likely to benefit from a particular therapy, even when that therapy is

at the earliest stage of clinical development.”