A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Monday, May 1, 2017

‘Jihadists were going to burn it all’: the amazing story of Timbuktu’s book smugglers

In

2012, tens of thousands of artefacts from the golden age of Timbuktu

were at risk in Mali’s civil war. This exclusive extract describes the

race to save them from the flames – and how lethal attacks could still

threaten the town’s treasures

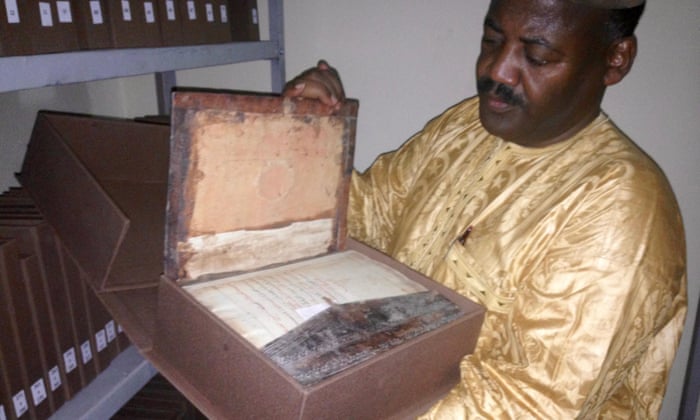

A damaged manuscript in Timbuktu in January 2013. Photograph: Benoit Tessier/Reuters-Abdel Kader Haidara showing rescued manuscripts in Bamako in 2015. Photograph: Charlie English

President Hollande in Mali in February 2013. Photograph: Fred Dufour/AFP/Getty Images--A restoration expert with one of the manuscripts in 2016. Photograph: Thomas Imo/Photothek via Getty Images--

Charlie English-Sunday 30 April 2017

One hazy morning in 2012 in Bamako, the capital of the west African state of Mali,

an ageing Toyota Land Cruiser picked its way to the end of a concrete

driveway and pulled out into the busy morning traffic. In its front

passenger seat sat a large man in billowing robes and a pillbox prayer

cap. He was 47 years old, stood over 6ft tall, and weighed around 14st,

and, although a small, French-style moustache balanced jauntily on his

upper lip, there was something commanding about his appearance. In his

brown eyes lurked a sharp, almost impish intelligence. He was Abdel

Kader Haidara, librarian of Timbuktu, and his name would soon become

famous around the world.

One hazy morning in 2012 in Bamako, the capital of the west African state of Mali,

an ageing Toyota Land Cruiser picked its way to the end of a concrete

driveway and pulled out into the busy morning traffic. In its front

passenger seat sat a large man in billowing robes and a pillbox prayer

cap. He was 47 years old, stood over 6ft tall, and weighed around 14st,

and, although a small, French-style moustache balanced jauntily on his

upper lip, there was something commanding about his appearance. In his

brown eyes lurked a sharp, almost impish intelligence. He was Abdel

Kader Haidara, librarian of Timbuktu, and his name would soon become

famous around the world.

Haidara was not an indecisive man, but that morning, as his driver

piloted the heavy vehicle through the clouds of buzzing Chinese-made

motorbikes and beat-up green minibuses that plied the city’s streets, he

was caught in an agony of indecision. The car stereo, tuned to Radio

France Internationale, spewed alarming updates on the situation in the

north, while the cheap mobile phones that were never far from his grasp

jangled continually with reports from his contacts in Timbuktu, 600

miles away. The rebels were advancing across the desert, driving

government troops and refugees before them. Haidara had known when he

left his apartment that driving into this chaos would be dangerous, but

now it was beginning to look like a suicide mission.

Responsable is a French noun whose meaning is easy to guess at

in English. There were few better words to describe the librarian then

than as a responsable for a giant slice of neglected history,

the manuscripts of Timbuktu, a collection of handwritten documents so

large no one knew quite how many there were, though he himself would put

them in the hundreds of thousands. The manuscripts contained some of

the most valuable written sources for the so-called golden age of

Timbuktu, in the 15th and 16th centuries, and the great Songhay empire

of which it was a part. They had been held up as proof of the

continent’s vibrant written history. Few had done more to unearth the

manuscripts than Haidara. In the months to come, no one would be given

more credit for their salvation.

In person, the librarian was an imposing man with a handshake of

astonishing softness, a drive-by of a greeting that left a hint of

remembered contact, no more. He was well versed in the history and

content of the documents, but appeared not so much a scholar as a

businessman who controlled his affairs in a variety of languages via his

mobile phones, or in person from behind a desk the size of a small

boat. He was not the only proprietor of manuscripts in the city, but as

the owner of the largest private collection and founder of Savama, an

organisation devoted to safeguarding the city’s written heritage, he

claimed to represent the bulk of Timbuktu’s manuscript-owning families.

Sitting in his car on the morning of 31 March, Haidara knew there was

only one place he should be. The cumbersome Land Cruiser made a U-turn

once again, and headed north-east, toward Timbuktu and the war.

Northern Mali had long been a rough neighbourhood, a refuge for bandits,

smugglers and revolutionaries. In 2011, an extra ingredient had been

added to the simmering stew. That year, a rebellion in Libya, backed by

Nato jets and cruise missiles, toppled the Gaddafi regime, and hundreds

of Malian Tuareg who had been employed in the dictator’s armies returned

home with all the weapons and ammunition they could carry. In Mali,

they joined forces with a political movement that had been campaigning

for an autonomous Tuareg state called Azawad, and the National Movement

for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) was born. The MNLA declared war on

the Bamako government and, with the aid of its al-Qaida allies,

inflicted a string of humiliating defeats on Mali’s demoralised

military. In mid-March 2012, a group of disaffected Malian army officers

launched a coup, and in the political chaos that followed, the rebels

took their opportunity, sweeping across the north as the army retreated

in disarray. The jihadists of al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)

were not far behind. They took over Timbuktu and governed it for almost a

year.

Haidara stayed in jihadist-occupied Timbuktu for a month, covertly

organising the hiding of his manuscripts in family houses. He then

returned to Bamako, where he began to consider moving them south. As a

Timbuktien, he didn’t yet have an office in the city but his American

friend Stephanie Diakité did. By October 2012, Haidara and Diakité had

become a team: in future months they would describe themselves as a

“consortium”, consisting of Haidara’s NGO Savama and Diakité’s

development organisation, D Intl. Fundraising was central to their

operation, and Diakité, in particular, had contacts among the foreign

governments and foundations she knew from her career in development. It

was these organisations that would end up donating the largest

quantities of cash.

One of them was an Amsterdam-based foundation, the Prince Claus Fund,

named for the husband of Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands. This fund,

which was supported by the Dutch government and the Dutch national

lottery, even had a “cultural emergency response” programme, set up in

the wake of the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in

Afghanistan in 2001. Deborah Stolk, the programme’s coordinator, had

never met Haidara and Diakité, but she felt he, in particular, “seemed

to have a good track record”. At the start of October, the information

Stolk was receiving from Bamako via email, phone and Skype was

increasingly alarming. In particular, Diakité told her the city’s

occupiers had implemented a “search-and-seize” policy in private homes

and businesses, and Haidara was growing concerned that manuscripts would

become the target.

On 8 October, Stolk received an email from Diakité informing her that

the manuscript-owning families of Timbuktu wanted Savama to evacuate

their collections. A lack of checks on the road south had provided a

window of opportunity. Diakité gave details of how it would work: the

documents would be taken to Bamako in lockers, each of which would

contain 250 to 300 documents, via two overland routes. Each shipment

would be accompanied by couriers recruited from the manuscript-owning

families, and there would be “supervisory and security personnel” camped

out all along both routes, ready to give “indirect support services”

and help in case of emergency. For extra security, each courier would

check in eight times a day, Stolk was told. Once in Bamako, the precious

manuscripts would be hidden in safe houses.

All that was missing was funding.

Stolk was convinced. She knew there was a risk involved in evacuating

the manuscripts, and that it might not succeed, but since there was

clearly an imminent threat, this seemed the best option.

On 17 October, the Prince Claus Fund signed a contract for the

evacuation of 200 lockers of manuscripts. The cost to the Dutch fund

would be €100,000, or roughly €500 a locker. The money wasn’t just for

transportation, but for “overall coordination, transportation costs,

couriers, mobile phones to be used during evacuation, stipendium for

families/safe houses” and so on, according to Stolk. According to a

later report of the evacuation in The New Republic that was fact-checked

by Diakité, the first shipments started to leave Timbuktu the day after

the Prince Claus contract was signed: “On 18 October, the first team of

couriers loaded 35 lockers on to pushcarts and donkey-drawn carriages,

and moved them to a depot on the outskirts of Timbuktu where couriers

bought space on buses and trucks making the long drive south to Bamako.”

That trip would be repeated daily for the next several months, according

to The New Republic, sometimes many times a day, as the teams of

smugglers passed hundreds of lockers along the same well-worn route to

Bamako.

The manuscripts’ journey south was fraught, and barely a day went by

without a courier ringing in with what Haidara described later as “petits problèmes”,

which ranged from mundane breakdowns to ransom demands and dangerous

run-ins with the jihadists. By the end of 2012, however, Savama informed

the German embassy in Bamako that between 80,000 and 120,000

manuscripts had been successfully evacuated from Timbuktu.

At this time, the Malian crisis was entering a far more dangerous phase.

In early January, the rebels began to advance south, taking Konna, 40

miles inside government territory, and on the morning of Friday 11

January, France’s president, François Hollande, announced that his

country was going to war. Operation Serval, the French offensive to

retake the north of Mali, was about to begin.

Haidara had been warned by heritage experts that the end of the

occupation of Timbuktu would be the most dangerous period for the

manuscripts: “People told me that the day they leave they are going to

burn everything. They are going to sabotage it all.”

He and Diakité now renewed their energetic fundraising. On Tuesday 15

January, Diakité pitched up at the Dutch embassy in Bamako for a meeting

with the embassy’s head of development aid, To Tjoelker. She told

Tjoelker the problem. “They said we would like you to help us because

there are still 180,000 manuscripts left in Timbuktu and we can’t get

them out without extra money,” the diplomat recalls. In particular,

Tjoelker was informed, the jihadists had threatened to burn the

manuscripts on the day of Mawlid, the celebration of the prophet’s

birthday, which fell on 24 January. “After the battle of Konna, the AQIM

fighters who were occupying Timbuktu became very angry,” she recalls.

“They said: ‘OK, we will show you. We will do a big auto-da-fé on the

day of Mawlid.’”

Tjoelker had no budget for saving culture, but Diakité had come knocking

at an opportune moment: the Dutch foreign minister, Lilianne Ploumen,

had just sent a note to the embassy asking what the government could do

to help Mali, and Tjoelker was convinced this was it. By 17 January,

Ploumen had given her blessing to the operation. The project had to

remain confidential: “I said to [Ploumen]: ‘You can’t tell anyone about

it, it has to be kept really secret because, if it becomes public

al-Qaida will react ... It is top secret and you can only get the

publicity after four or five months but not now, you have to keep

quiet.’”

Embassy staff took this entreaty so seriously they even marked down the

money they gave the book smugglers as being for school exercise books in

their own accounts.

The Dutch foreign ministry allocated €323,475 to Savama and that

afternoon, Tjoelker began to make arrangements. On Saturday 19 January,

she took the contract to the librarian for him to sign, meeting him in

the Bamako lockup where the manuscripts were being received and

dispatched to the safe houses. He looked unwashed, she remembered, and

“so tired”, and to cheer him up she told him the work he was doing was

“important for all humanity”. The contract stipulated that he would

evacuate 454 lockers, or 136,200 manuscripts, which meant the cost of

transporting each had now reached a whopping €660, though this included

storage for a year, the making of an inventory, at €212 for each locker,

and a 10% “management fee” for Savama and for D Intl.

The manuscripts would now be moved by boat, Tjoelker was told, since the

French advance meant it was too dangerous to drive to Timbuktu. “That

weekend, a large numbers of boats – around 20 – were already starting to

leave Timbuktu,” she says. These travelled 250 miles upriver, across

the inland delta and Lake Debo, to Mopti, where they turned south up the

Bani river for a further 70 miles to Jenne, where the lockers were

transferred to bush taxis that took the manuscripts the last 350 miles

to Bamako by road.

Once or twice during the operation, the Dutch ambassador, Maarten

Brouwer, asked how things were going, and recalled being told of

difficulties on the route: “We got some stories about [lockers] full of

manuscripts that were transported by pirogues [dugout canoes]

and that it was done during the night, and they had a lot of problems on

the way because there was the police, there were rebels, and so on,” he

says. He had heard that boats had been kidnapped or that people had

threatened to set manuscripts on fire. “It was the people on the ground

that solved those issues.”

As the lockers reached Bamako, Haidara took Tjoelker to see them. “He

really made me part of the reception of all those boxes. Every box had a

number and the name of the funder on it so they knew who had paid for

what.” Brouwer accompanied Tjoelker on one of these visits. He counted

roughly 500-600 containers in the room, easily enough for Savama to have

fulfilled its contract with the Dutch government, and was told there

were more elsewhere. “I looked at To [Tjoelker] and I said: ‘This is a

lot. Are these all full?’ They said: ‘Yes, they are all full.’”

To be doubly sure, he even singled out one chest-deep in a stack at the back of the stockroom and said: “OK, show me that one.”

When the locker was opened, he saw it was piled to the brim with manuscripts.

Postscript: On 2 February 2013, after Operation Serval had

succeeded in recapturing northern Mali, François Hollande stood in

Timbuktu as the city’s hero and liberator. French troops kept Mali

secure for a short time, but the situation has long since deteriorated.

Once again, innumerable armed groups of different beliefs and

ethnicities are fighting for a slice of the country’s future.

According to the Malian journalist Ousmane Diadié Touré, who frequently

travels to Timbuktu and the north, security is now as bad as ever. “All

the forces have had time to reorganise and are now pursuing different

strategies,” he says. Though some al-Qaida commanders were killed in

2013, many of those who led the rebellion are still in business. In

January this year, more than 70 soldiers died and 100 were injured in

what is described as the most lethal terrorist attack in the country’s

history, on a military base in Gao. The jihadist insurgency also seems

to be spreading: since 2015, a new group, the Macina Liberation Front,

has brought terror to the centre and south of the country.

Timbuktu town itself is still secure, with a UN blue helmet force

regularly patrolling the streets. However, the wider political situation

has had a significant effect on the economy, since the tourists who

provided a substantial portion of Mali’s income no longer come. Business

is going “very badly for the librarians”, says Abdoulwahid Haidara, the

proprietor of the town’s Mohamed Tahar manuscript library.

Four years after Timbuktu’s liberation, many of its manuscript libraries

remain in the south and only two libraries are now open in the city

itself, he says. He hopes his own Mohamed Tahar library will reopen its

doors in a month’s time, when renovation work by Unesco is complete.

Extracted from The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu by Charlie English,

published by William Collins on 6 May. The book is published the US by

Riverhead, under the title The Storied City.