A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Friday, June 30, 2017

Trump’s pledge to keep the world from laughing at us hits another setback

Commerce

Secretary Wilbur Ross was cut off then laughed at while speaking by

teleconference at a gathering of the Economic Council of the Christian

Democratic Union in Berlin. (Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post)

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross was supposed to attend this week’s

Economic Council of the Christian Democratic Union meeting in Berlin,

but suddenly canceled his travel plans on Tuesday. Ross was scheduled to

give an address at the conference immediately before German chancellor

Angela Merkel, so he instead gave his remarks by teleconference from

Washington.

Ross was allotted 10 minutes to speak. After speaking for more than 20,

the conference organizers cut his feed mid-sentence. The audience

“laughed and clapped” in response, according to Bloomberg. Merkel then

rose and, during her remarks, disagreed with one of Ross’s points.

The relationship between President Trump and Merkel has been strained

since his inauguration. His repeated insistence that Germany owes money

to NATO and his unusual reticence to embrace that alliance has been one

point of friction. His disparagement of Germany as “very bad” in a

closed-door meeting was another. That claim centered on what Trump (and

Ross) viewed as a trade disparity between the two countries and was the

point with which Merkel took issue.

In most other contexts, a laughing reaction from a small group of

America’s economic and geopolitical allies would be odd but not

particularly noteworthy. In the context of the Trump administration,

though, it’s telling.

Trump’s campaign rhetoric repeatedly centered on the idea that America

was being laughed at internationally. His evidence for this claim was

lacking, but it was a point he raised repeatedly.

During his campaign launch, he said Mexico was “laughing … at our

stupidity” on the border. In a speech before the Iowa caucuses, Trump

claimed that the Islamic State was laughing at our leaders, a claim he

repeated in a March debate. The whole world was laughing at us because

of Barack Obama, he said in an interview in May of 2016 — and in

speeches in June and October. As Election Day approached, he made the

claim over and over.

When he announced that he was withdrawing the United States from the

Paris climate accord last month, Trump claimed that it was necessary

because we’d gotten a bad deal — so bad that we were being laughed at.

“The Paris agreement handicaps the United States economy in order to win

praise from the very foreign capitals and global activists that have

long sought to gain wealth at our country’s expense. … The same nations

asking us to stay in the agreement are the countries that have

collectively cost America trillions of dollars through tough trade

practices and, in many cases, lax contributions to our critical military

alliance,” he said. “At what point does America get demeaned? At what

point do they start laughing at us as a country? We want fair treatment

for its citizens, and we want fair treatment for our taxpayers. We don’t

want other leaders and other countries laughing at us anymore. And they

won’t be. They won’t be.”

On Tuesday, The Post highlighted new survey data from the Pew Research

Center showing that perceptions of America and our president have

decreased substantially in most parts of the world following Trump’s

election. That includes Germany — a country to which Trump was pointedly

referring in his Paris remarks and where Trump’s commerce secretary was

laughed at literally.

Views of the American people have held fairly constant over the years

among Germans, Pew’s polling revealed. But views of our government and

president slipped during the George W. Bush administration, rose under

Barack Obama — and then collapsed this year.

German confidence in the American president followed the same pattern.

Last year, 86 percent of Germans had a lot of or at least some

confidence in America’s president. This year, more than half have none

at all.

It’s easy to read too much into the reaction Ross prompted this week.

But as a symbol of the relationship between the two countries at the

moment, it’s hard not to — particularly given how often other countries’

laughter was raised by Trump as something we should be concerned about.

Britain’s social mobility crisis in ten graphs

- By Martin Williams28 JUN 2017

A damning new report has criticised politicians’ efforts to improve social mobility.

The research, by the Social Mobility Commission, warns that for years

policies have “failed to deliver enough progress in reducing the gap

between Britain’s ‘haves and have nots’.”

“The old agenda has not delivered enough social progress,” it says. “The

policies of the past have brought some progress, but many are no longer

fit for purpose in our changing world.”

So, how bad is it? Here are ten key graphs from the Social Mobility Commission’s report that paint a picture of the problem.

- By Martin Williams28 JUN 2017

The research, by the Social Mobility Commission, warns that for years policies have “failed to deliver enough progress in reducing the gap between Britain’s ‘haves and have nots’.”

“The old agenda has not delivered enough social progress,” it says. “The policies of the past have brought some progress, but many are no longer fit for purpose in our changing world.”

So, how bad is it? Here are ten key graphs from the Social Mobility Commission’s report that paint a picture of the problem.

1. Child development equality has flatlined

This graph shows the percentage-point gap between deprived and

non-deprived areas for children who reach a good level of development by

the age of five. It was improving, but has now flatlined.

2. If your parents are not highly educated, you receive less child development time

The gap has got wider over time. Here, we can see the number of minutes that parents spend on their child’s development per day, in 2001/01 and 2014/15.

3. There’s still a big gap between rich and poor children at school

This shows the percentage of pupils who achieve at least level 2 in Key Stage 1. It’s broken down by those children who are eligible for free school meals (FSM), and those who are not.

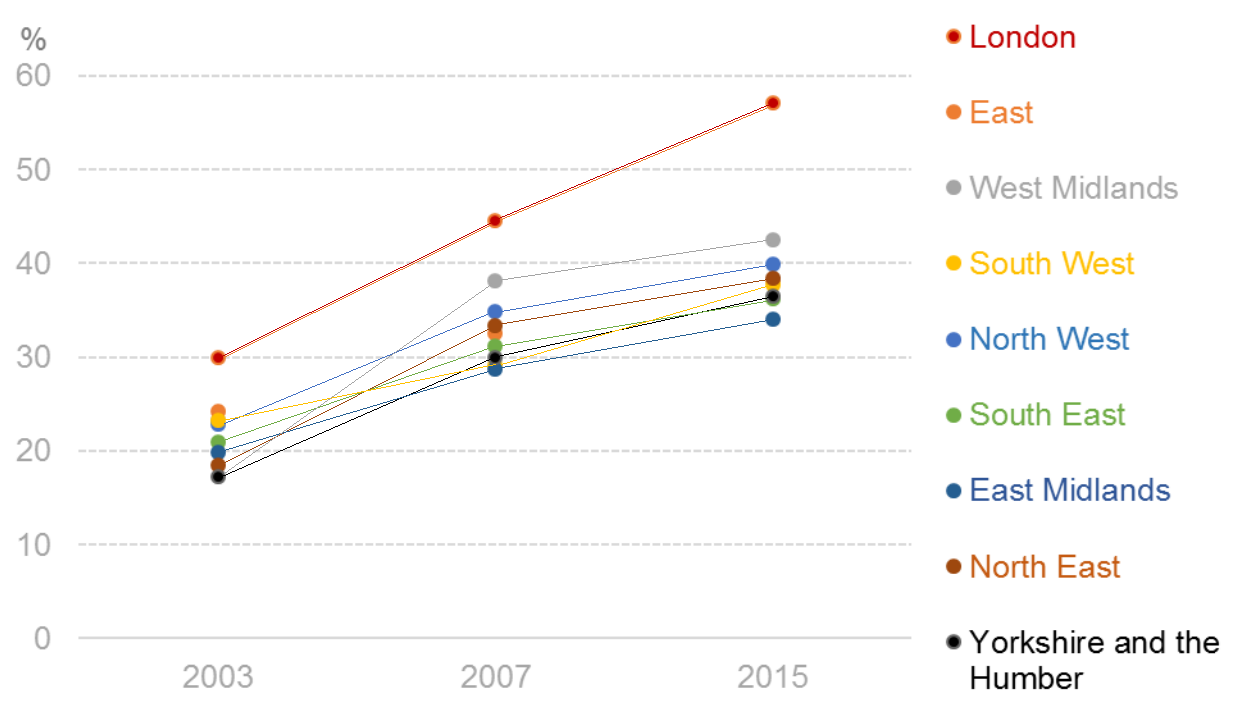

4. Attainment for poorer children is improving quicker in London than the rest of England

As above, this graph is based on pupils who are eligible for free school meals. It shows the percentage who achieved at least five A*-C grades at GCSEs, or equivalent. (We’ve added the coloured lines on to the Social Mobility Commission’s graph to make it easier to track each region’s progress).

5. Good school leadership is linked to location and deprivation

The percentage of secondary schools with “good and outstanding” leadership is far lower in deprived areas outside London. This graph shows the breakdown by both region and deprivation in 2016.

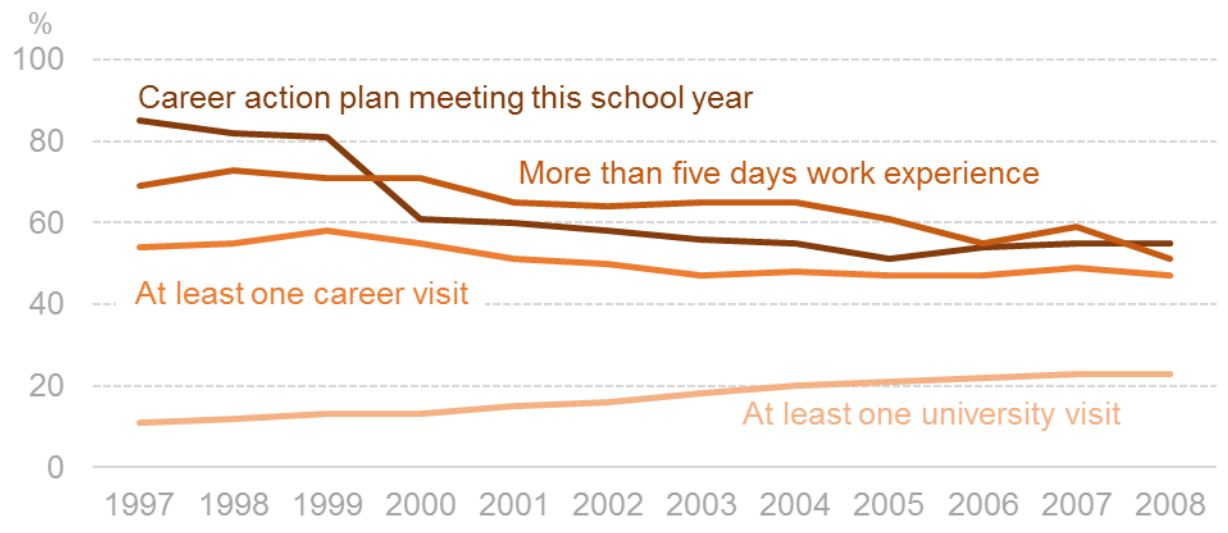

6. Careers advice in schools is declining

This one shows the percentage of schools offering career support between 1997 and 2008. Every category of support has decreased except university visits, which have slowly become more widespread.

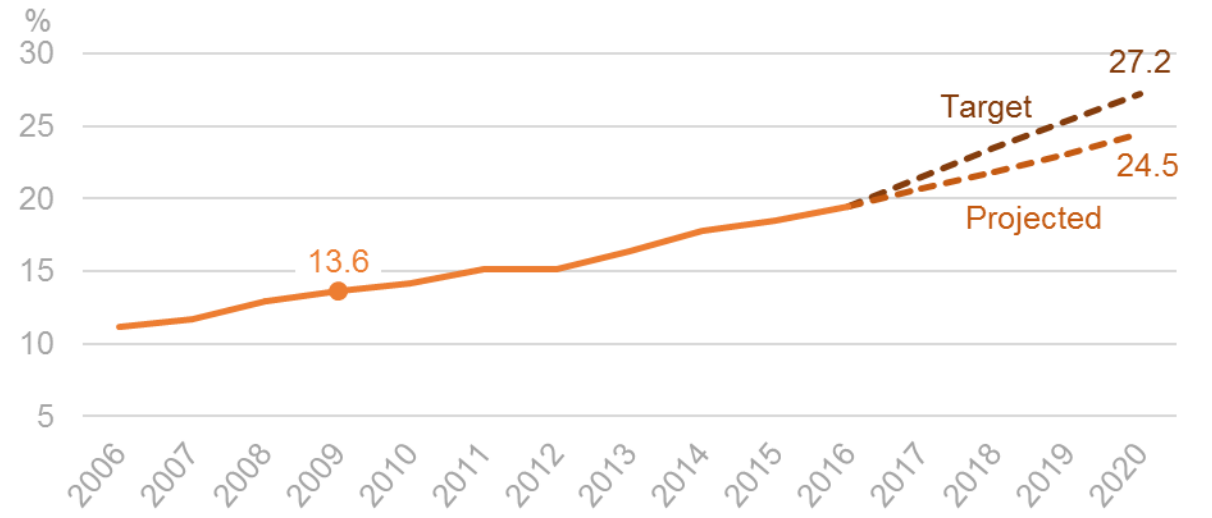

7. University access is improving… but the government is set to miss its target

The government wanted to double university access for students from low-participation areas by 2020. It looks like that won’t happen, but there is steady progress nevertheless.

8. University access improvements are driven by poorer students going to the least selective universities

The percentage of disadvantaged 18-year-olds entering higher education has increased the most among those who go to low entry tariff institutions.

9. Social mobility has improved much more in some professions than others

This graph shows the percentage of people at the top of a sample of professions who went to private schools, in 1987 and in 2016. This demographic continues to dominate among barristers and the judiciary, and have actually increased in proportions in journalism and medicine. But the percentage of privately educated CEOs has dropped dramatically.

10. Most poor people live in working households

People who are in poverty are less likely to be unemployed than they were 20 years ago. Unemployment has fallen but wages have stayed low since the financial crisis, meaning the percentage of people suffering from in-work poverty has gone up.