A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Saturday, May 5, 2018

Revived in the west, neglected in the east: how Marx still divides Germany

The fate of a statue highlights contrasting attitudes on eve of the philosopher’s 200th birthday

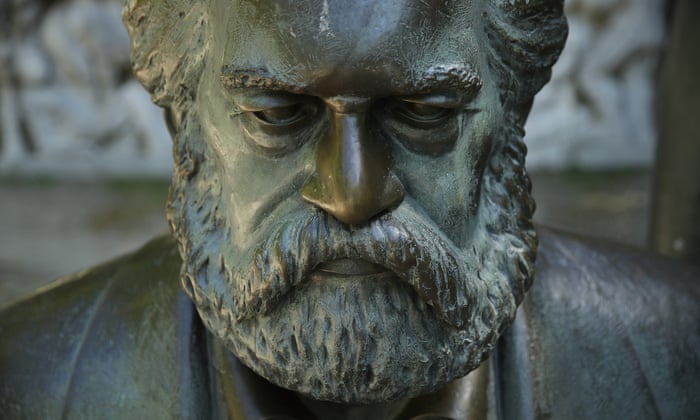

A statue of Karl Marx in Berlin. Dignitaries from around the world will travel to his birthplace in Trier to mark his 200th birthday. Photograph: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Philip Oltermannin Neubrandenburg @philipoltermann-

Throughout the cold war, Karl Marx stood tall and proud in the centre of Neubrandenburg, a socialist model town in Germany’s north-east. Rising to 2.2metres (7ft 2in) and made of bronze, the sculptor Gerhard Thieme’s 1969 memorial showed the bearded thinker facing the capitalist west with a grim-eyed snarl.

But as dignitaries from around the world flock to the German philosopher, economist and revolutionary socialist’s birthplace in Trier on Saturday for his 200th birthday, the Neubrandenburg Marx will be snarling only at the ceiling of a warehouse on the outskirts of town.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the town’s Karl Marx Square has been renamed Market Square and on the spot once reserved for the man behind the theory of commodity fetishism now stands a shopping centre retailing fridges, sneakers and push-up bras.

Marx, a thinker with a clear notion of the proximity between tragedy and farce, might well have appreciated the topsy-turvy situation in the land of his birth: while a revival of his ideas is in full swing in what was once the capitalist west, the part of the country that for four decades tried to put Marxist thinking into practice now keeps a cool distance.

In Trier, in the south-west, politicians including the European commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, and Germany’s Social Democrat leader, Andrea Nahles, will give speeches at the unveiling of a 5.5 metre-high statue gifted by the Chinese government, which has been welcomed even by members of Angela Merkel’s centre-right Christian Democratic Union.

“Thirty years ago, such a statue wouldn’t have been possible,” said Wolfram Leibe, Trier’s Social Democrat mayor. “But today, with more distance to the socialism of the German Democratic Republic, is the right time to engage with Marx in this form too.”

Marx’s Das Kapital is climbing back into the bestseller charts and a raft of biographies and TV dramas celebrate the enduring relevance of his ideas. Even Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, the centre-right bourgeoisie’s broadsheet of choice, last Sunday put Marx on its front page and let its staff writers choose their favourite passages from his oeuvre.

Thomas Steinfeld, a former editor of Süddeutsche Zeitung’s reviews section and author of a recently published book on Marx’s philosophy, said a revival of Marxist thinking had been in full swing since the 2008 financial crisis. “The economists on our business pages were only able to explain the market as a system that worked. But the crisis forced us to confront Marx’s alternative: what if markets are latently catastrophic?

“We live in an age that is as pious as the middle ages, but now we define ourselves not through a divine order but capital relation. Going back to Marx allows us to recognise this condition from the outside.”

The

Neubrandenburg mayor, Silvio Witt, with the statue of Marx that used to

stand in the city. Photograph: Philip Oltermann for the Guardian

The

Neubrandenburg mayor, Silvio Witt, with the statue of Marx that used to

stand in the city. Photograph: Philip Oltermann for the Guardian

Dieter Kowallick, a local politician for the leftwing Die Linke party in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, said: “When it comes to reading Marx, the west is now more progressive than the east.” In the run-up to the anniversary, Kowallick and his comrades had proposed the Neubrandenburg Marx be re-erected in the city.

But the task of finding an appropriately symbolic location proved divisive. While leftwingers wanted to see the philosopher outside the local library, other members of the senate insisted Marx be placed outside the former Stasi prison, to remind people of the injustices committed in his name.

“Is Marx sleeping? Has he been toppled? Or does he just need a breather?” said Witt of his proposal, which was eventually rejected by Die Linke, who hold a majority in the senate.

“If we had put Marx back in his place without commentary, that wouldn’t have made sense. We needed a monument that expresses a certain amount of discomfort with his heritage,” said Witt, sitting in his office at the town hall, a German Democratic Republic-era building on a ring road called Friedrich-Engels-Ring.

While Marx’s bearded face was everywhere in East Germany – on the classroom walls during Witt’s youth or the 100 ostmark bill – the ruling socialist party treated his writing less as a theory to be critically engaged with than a science. Those who questioned whether the GDR’s existing socialism was really in keeping with Marx’s writing, such as the dissident writers Robert Havemann or Rudolf Bahro, were expelled either from the party or the country.

The

sculpture of Marx lies on a pavement in Neubrandenburg, awaiting a

decision on its future. Photograph: Philip Oltermann for the Guardian

The

sculpture of Marx lies on a pavement in Neubrandenburg, awaiting a

decision on its future. Photograph: Philip Oltermann for the Guardian

“In the east Marx was omnipresent, and yet, in an odd way, most people felt like they never really knew him,” said Christina Morina, an East Germany-born historian whose recent book The Invention of Marxism examines the people who turned the philosopher’s ideas into a political movement.

“What citizens in the GDR knew was Marx through the rigid prism of Lenin, Stalin or [the former East German head of state Walter] Ulbricht. The state had no interest in them finding their own way into his work.”

While Morina largely blames Marx’s interpreters for East Germany’s experiment with authoritarian Marxism, she also suggests that the contemporary revival’s pick-and-mix approach overlooks the 19th-century thinker’s absolutist ambitions.

“There was a megalomania – and a dash of Prussian authoritarianism – to Marx’s desire to read and write his way into all sorts of scientific disciplines,” Morina said.

In Neubrandenburg, a place once run on principles of Marxist economics, Witt is convinced that his city has prospered since state-run businesses were privatised after the fall of the wall. In one of Germany’s structurally weaker states, the city now has the greatest taxpaying ability.

Still, not everybody agrees. “We have never been in an economically stabler position – and yet many people complain that they feel insecure. The GDR felt like a stable society to its citizens, but as a system it was instable. Now it is the other way around.”

Before the end of the year, Neubrandenburg’s citizens will once again be able to consult Marx for answers to this dilemma. After hours of fractious debates, the mayor has agreed that the statue will again go on display in 2018 as part of the city’s art collection – standing upright.

Throughout the cold war, Karl Marx stood tall and proud in the centre of Neubrandenburg, a socialist model town in Germany’s north-east. Rising to 2.2metres (7ft 2in) and made of bronze, the sculptor Gerhard Thieme’s 1969 memorial showed the bearded thinker facing the capitalist west with a grim-eyed snarl.

But as dignitaries from around the world flock to the German philosopher, economist and revolutionary socialist’s birthplace in Trier on Saturday for his 200th birthday, the Neubrandenburg Marx will be snarling only at the ceiling of a warehouse on the outskirts of town.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the town’s Karl Marx Square has been renamed Market Square and on the spot once reserved for the man behind the theory of commodity fetishism now stands a shopping centre retailing fridges, sneakers and push-up bras.

Marx, a thinker with a clear notion of the proximity between tragedy and farce, might well have appreciated the topsy-turvy situation in the land of his birth: while a revival of his ideas is in full swing in what was once the capitalist west, the part of the country that for four decades tried to put Marxist thinking into practice now keeps a cool distance.

In Trier, in the south-west, politicians including the European commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, and Germany’s Social Democrat leader, Andrea Nahles, will give speeches at the unveiling of a 5.5 metre-high statue gifted by the Chinese government, which has been welcomed even by members of Angela Merkel’s centre-right Christian Democratic Union.

“Thirty years ago, such a statue wouldn’t have been possible,” said Wolfram Leibe, Trier’s Social Democrat mayor. “But today, with more distance to the socialism of the German Democratic Republic, is the right time to engage with Marx in this form too.”

Marx’s Das Kapital is climbing back into the bestseller charts and a raft of biographies and TV dramas celebrate the enduring relevance of his ideas. Even Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, the centre-right bourgeoisie’s broadsheet of choice, last Sunday put Marx on its front page and let its staff writers choose their favourite passages from his oeuvre.

Thomas Steinfeld, a former editor of Süddeutsche Zeitung’s reviews section and author of a recently published book on Marx’s philosophy, said a revival of Marxist thinking had been in full swing since the 2008 financial crisis. “The economists on our business pages were only able to explain the market as a system that worked. But the crisis forced us to confront Marx’s alternative: what if markets are latently catastrophic?

“We live in an age that is as pious as the middle ages, but now we define ourselves not through a divine order but capital relation. Going back to Marx allows us to recognise this condition from the outside.”

The

Neubrandenburg mayor, Silvio Witt, with the statue of Marx that used to

stand in the city. Photograph: Philip Oltermann for the Guardian

The

Neubrandenburg mayor, Silvio Witt, with the statue of Marx that used to

stand in the city. Photograph: Philip Oltermann for the GuardianDieter Kowallick, a local politician for the leftwing Die Linke party in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, said: “When it comes to reading Marx, the west is now more progressive than the east.” In the run-up to the anniversary, Kowallick and his comrades had proposed the Neubrandenburg Marx be re-erected in the city.

But the task of finding an appropriately symbolic location proved divisive. While leftwingers wanted to see the philosopher outside the local library, other members of the senate insisted Marx be placed outside the former Stasi prison, to remind people of the injustices committed in his name.

The city’s mayor, Silvio Witt, a former comedian and entrepreneur who ran for office as an independent, proposed a compromise: what if Thieme’s sculpture returned to Neubrandenburg, but lying horizontally on his back?When it comes to reading Marx, the west is now more progressive than the east

“Is Marx sleeping? Has he been toppled? Or does he just need a breather?” said Witt of his proposal, which was eventually rejected by Die Linke, who hold a majority in the senate.

“If we had put Marx back in his place without commentary, that wouldn’t have made sense. We needed a monument that expresses a certain amount of discomfort with his heritage,” said Witt, sitting in his office at the town hall, a German Democratic Republic-era building on a ring road called Friedrich-Engels-Ring.

While Marx’s bearded face was everywhere in East Germany – on the classroom walls during Witt’s youth or the 100 ostmark bill – the ruling socialist party treated his writing less as a theory to be critically engaged with than a science. Those who questioned whether the GDR’s existing socialism was really in keeping with Marx’s writing, such as the dissident writers Robert Havemann or Rudolf Bahro, were expelled either from the party or the country.

The

sculpture of Marx lies on a pavement in Neubrandenburg, awaiting a

decision on its future. Photograph: Philip Oltermann for the Guardian

The

sculpture of Marx lies on a pavement in Neubrandenburg, awaiting a

decision on its future. Photograph: Philip Oltermann for the Guardian“In the east Marx was omnipresent, and yet, in an odd way, most people felt like they never really knew him,” said Christina Morina, an East Germany-born historian whose recent book The Invention of Marxism examines the people who turned the philosopher’s ideas into a political movement.

“What citizens in the GDR knew was Marx through the rigid prism of Lenin, Stalin or [the former East German head of state Walter] Ulbricht. The state had no interest in them finding their own way into his work.”

While Morina largely blames Marx’s interpreters for East Germany’s experiment with authoritarian Marxism, she also suggests that the contemporary revival’s pick-and-mix approach overlooks the 19th-century thinker’s absolutist ambitions.

“There was a megalomania – and a dash of Prussian authoritarianism – to Marx’s desire to read and write his way into all sorts of scientific disciplines,” Morina said.

In Neubrandenburg, a place once run on principles of Marxist economics, Witt is convinced that his city has prospered since state-run businesses were privatised after the fall of the wall. In one of Germany’s structurally weaker states, the city now has the greatest taxpaying ability.

Still, not everybody agrees. “We have never been in an economically stabler position – and yet many people complain that they feel insecure. The GDR felt like a stable society to its citizens, but as a system it was instable. Now it is the other way around.”

Before the end of the year, Neubrandenburg’s citizens will once again be able to consult Marx for answers to this dilemma. After hours of fractious debates, the mayor has agreed that the statue will again go on display in 2018 as part of the city’s art collection – standing upright.