A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Saturday, May 5, 2018

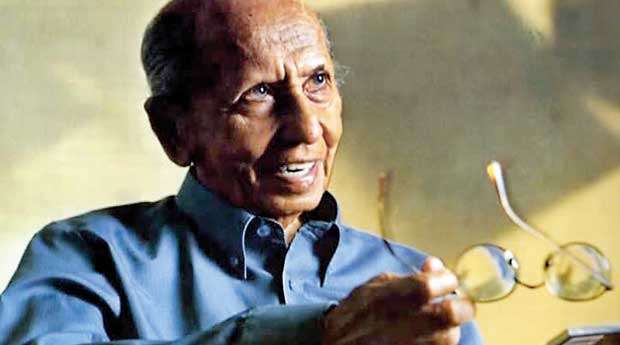

That’s the beauty of the man, Lester

Lester James Peries was that day, honoured as the longest living reputed film director in the world

It

was only after ‘Rekawa’ was acclaimed as the path breaking Sinhala film

that Lester came to be spoken of as the Sri Lankan version of

Sathyajith Ray

Lester also picked on two ‘naturally Sinhala’ voices for vocals, in Sisira Senaratne and Indrani Wijebandara

A birthday cake was cut on his 99th birthday that fittingly celebrated with wife Sumithra’s film “Vaishnavi” premièred

at the Regal Cinema Colombo on 05 April (2018), attended by the most

elite and the celebrated audience one could ever expect in Colombo.

He, Lester James Peries was that day, honoured as the longest living

reputed film director in the world.The oldest active film director on

record is the famous Portuguese Director Manoel de Oliveira, who in 2014

at the grand old age of 104 years, directed the film, “The Old Man of

Belem”.

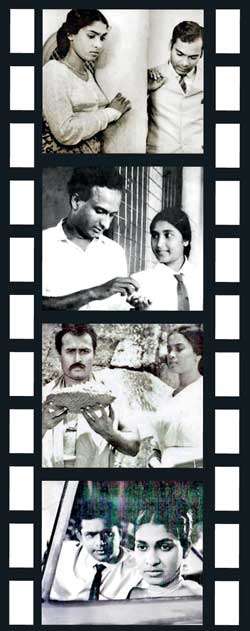

Lester’s last feature film was “Ammawaruney” (Mothers) directed in 2006 when he was 87 years in age. With “Ammawaruney” he completed 20 feature films, beginning with “Rekawa” (Line of destiny), the path breaking Sinhala film released in December 1956.

The year ‘1956’ is a very significant year in our post independent history, both politically and culturally. Politically, it brought to culmination the ride of Sinhala Buddhist politics to dominance with Bandaranaike voted PM and Sinhala made the only official language. It was a coincidence for Sinhala Buddhists to have the opportunity to celebrate Vesak as “Buddha Jayanthi” the 2,500 year anniversary of the ‘Final passing away’ of Lord Buddha. In arts and culture, Ediriweera Sarachchandra’s epic stylised drama “Maname” was staged in Colombo heralding a new beginning in Sinhala stage drama, followed by Lester James Pereis’s film “Rekawa”.

At the 1957 Cannes international film festival, ‘Rekawa’ was well received although it forced Lester’s film production company “Chitra Lanka Limited” to put up shutters. Lester’s daring to leave studios and sets to shoot outdoor did not lift it commercially high. But that radical decision to go on location was path breaking. Ignoring the then formula of a 02 hour 30 minute film with a hero, villain, romance, fighting, comedy and a long list of songs with Dravidian melodies in a family setting and to go to a rural Sinhala Buddhist village to narrate a simple story woven around a young village boy was also high risk and path breaking too. No fighting, no romance, no hero or villain as such, but some wit and real life humanity, left ‘Rekawa’ meek in the box office.

From his second film ‘Sandeshaya’ (1960) through ‘Gamperaliya’ (1963) to ‘Ransalu’ (1967), ‘Goluhadawatha’ (1968), Nidhanaya (1972) to ‘Madolduwa’ (1976), he borrowed most such stories from reputed Sinhala novelists

It is interesting to place Lester alongside his own film ‘Rekawa’ that

was wholly rural in context and in a way was alien life for Lester. He

was born to a very conservative, elite and an affluent Roman Catholic

family in Dehiwala. Was schooled at St. Peters’ College Bambalapitiya

and began his young life as a junior journalist with the English

newspaper “Daily News” first and then “Times of Ceylon”. He tried his

hand at fiction with 02 short stories, “The Teacher” and “Saree”. None

about rural life he wasn’t ever familiar with. After about 10 years of

journalism, he left to London in 1947. There he was drawn into films in a

completely different cultural milieu, with amateur film clubs growing

fast in developing cinema with experimenting.

His first attempt in directing was in 1949 with “Farewell to Childhood” based on his own short story “Saree”. Completing it in 1950 he was recognised for its creativity and was awarded the ‘Amateur Cine World Silver Plaque’ judged as one among the 10 best amateur films that year. In 1951 he teamed up with Hereword Jansz another Sri Lankan of Dutch Burgher origin who was the cameraman in the short 20 minute film “Soliloquy”. This was awarded ‘The Mini Cinema Cup for Short Films’ for its technical proficiency in 1951 by the ‘Institute of Amateur and Experimental Film Makers Festival-Great Britain’.

In late 1952 he returned and in just 03 plus years, scripted and directed ‘Rekawa’ a film set in a rural Sinhala Buddhist village that with superstitions, myths, rituals and beliefs, was completely different to his upbringing and grooming both in Colombo and in London. He had not seen or been influenced by the Bengali film director, the Indian ‘Great’ Sathyajith Ray when he laid his hands on Rekawa. It was only after ‘Rekawa’ was acclaimed as the path breaking Sinhala film that Lester came to be spoken of as the Sri Lankan version of Ray. Sathyajith Ray was internationally recognised with his film “Patharpanchali” (1955) and then “Aparajitho” (1956) that came before ‘Rekawa’. They were two South Asian film directors who broke into stardom and recognition, each on his own.

It is interesting to place Lester alongside his own film ‘Rekawa’ that was wholly rural in context and in a way was alien life for Lester

Lester and village life in ‘Rekawa’ is attributed to his close working relationship with Ralph Keene a Britisher who was invited in 1952 to head the Government Film Unit (GFU). Keene knew Ceylon well having made a documentary “String of Beads” in 1947, for tea propaganda. In 1952 his script directed by George Wickramasinghe documented the lives of Negombo fishermen. The second was “The Heritage of Lanka” that covered Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Mihintale and Sri Pada. Keene was giving his documentaries a very local touch with musical scores that used folk rhythms and melodies. For the musical score in “The Heritage of Lanka” he had renowned Singer/musician Deva Surya Sena. Lester was Keene’s Assistant Director. That gave Lester good insight into Lanka’s heritage but it was Keene’s next documentary in 1953, that documented the rural village life, titled “Nelungama” that actually led Lester to ‘Rekawa’.

After Keene left Ceylon, George Wickramasinghe was head, GFU. That led to more documentaries on local issues and “Conquest of the Dry Zone” produced in 1954 is one masterpiece among them. It was on the Ceylonese health service that successfully controlled the raging Malaria epidemic, the best success story on public health in Asia. This earned Lester much applause for his direction and it had special mention at the Venice Film Festival. “Conquest of the Dry Zone” captured the hard lif eand exposed Lester to myths and rituals in the ordinary rural life, Lester dwells on in ‘Rekawa’.

Like Keene, Lester too brought together two ‘out of the ordinary’ personalities to write songs and create melodies for ‘Rekawa’. Both from the “Hela school” of Sinhala. One was Rev. Fr. Mercelline Jayakody the reputed lyricist and the other, also a Catholic, B. Don Joseph John, much respected for his pioneering work in Sinhala music and song, the stubborn experimentalist Sunil Santha. Lester also picked on two ‘naturally Sinhala’ voices for vocals, in Sisira Senaratne and Indrani Wijebandara. He thus created a marvel in Sinhala film, from where the Sinhala films began a new journey.

Lester’s film life marks two phases that overlap each other. The first phase up to the beginning of the free market economy in 1978 marks a period he was accepted and honoured as the undisputed doyen of Sinhala film that reached the rural and urban middle class. Although he gradually settled within his comfortable urban life, it was a slow moving city life.There was time and space for leisure. His films in general revolved around human life that was in no hurry to leave ‘today’ to catch ‘tomorrow’as soon as possible. From his second film ‘Sandeshaya’ (1960) through ‘Gamperaliya’ (1963) to ‘Ransalu’ (1967), ‘Goluhadawatha’ (1968), Nidhanaya (1972) to ‘Madolduwa’ (1976), he borrowed most such stories from reputed Sinhala novelists Martin Wickramasinghe, Karunasena Jayalath and G.B. Senanayake. He was thus the icon of the pre ‘free market’ middle class film world.

His second phase overlapping the previous in terms of his focus on human life, was nevertheless in a different socio economic and political context. Free market economy was pushing society into faster and new consumerised relationships quite different to the slow and peaceful life before that Lester was comfortable with. The free market consumer life was also dragged into an ethnic conflict turning it into a brutal and a savage war that was concluded 03 years after his last film ‘Ammawarune’ (2006). Yet Lester was in no mind to cinematically de-construct those new human relationships in his creations. He stood aloof from all the turmoil around him, with old stories like Baddegama (1980), Kaliyugaya (1982), Yuganthaya (1983) picked from novels written by Leonard Wolfe and Martin Wickramasinghe. His one before the final contribution to Sri Lankan cinema, ‘Wekande Walauwa’ (2002) was a Sinhala adaptation of Anton Chekov’s play “Cherry Orchard”.

For the new generations in fast moving free market economy there was a

mismatch between their turgid and taut lives and Lester’s passive and

a-political creations.That distance was nevertheless narrowed with

Lester’s mastery in storytelling in visual form, his cinematic language

and his towering reputation as the pioneering architect of Sinhala

cinema. In his second phase he therefore remained, not as the radical

film director who broke with tradition in directing ‘Rekawa’ but as the

matured craftsman of cinematic creation who directed ‘Nidhanaya’, from

one of G.B. Senanayake’s short stories. Lester’s selection of Tissa

Abeysekera as script and dialogue writer who gelled with his art of

storytelling, was lifted to international heights with Kemadasa Master’s

rich and haunting music. Gamini and Malini Fonseka giving off their

best,‘Nidhanaya’ lies among the best 100 films made during 100 years of

global cinema, as compiled by the French organisation ‘Cinematheque

Institute’.

Once over his usual “scotch on rocks” at his private residence, I had a casual chat with Gamini Fonseka the ‘Lord of Sri Lankan Cinema’s one time in 1990, when I asked him how he fared with Lester James Peries as a director, turning out two superb roles in ‘Gamperaliya’ and ‘Nidhanaya’. Silent for a few seconds, he sipped on his scotch before saying, “Never drove me to deliver what he wanted. Just told me what he wants and sometimes left me to play what I understood. That’s the beauty of the man as a director”.

In appreciation of Lester James Peries who passed away on 29 April, 2018 at the age of 99 years.