A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Sunday, August 12, 2018

Evolution of plantation sector into diversified, vertically-integrated, globally aligned, agri-biz

From its inception up to the present day, the history of Sri Lanka’s

plantation industry has been unique; undergoing drastic changes from the

colonial era, to the period of private management by Agency Houses,

into an extended period of nationalisation and finally and most

drastically through the sustained transformations that the plantation

sector has undergone subsequent to the 1992 privatisation.

In order to truly appreciate the present circumstances and performance

of this industry and the role of the Regional Plantation Companies

(RPCs) in particular, it is vital to consider the development of our

industry as a whole.

Today’s international markets are changing at an increasing pace, while

the threat of climate change continues to cause varying disruptions to

agricultural productivity across the globe. At this crucial juncture, we

assert that our entire industry must be viewed in its totality in order

to ascertain the true reasons as to why Sri Lankan RPCs have achieved

such success across so many key areas today – from improvements in the

socio-economic conditions of its employees on the estates to substantial

improvements in quality control, management techniques and

infrastructure – in order to accurately ascertain what more is required

of each and every stakeholder group and to ensure commercial,

environmental and social sustainability for the Sri Lankan plantation

industry moving forward.

While coffee might seem to be the ‘go-to’ drink for those seeking a hot

beverage, the world actually runs on tea. Aside from water, tea is the

most popular beverage in the world and in the United States alone; tea

imports have risen over 400% since 1990. It would be futile if we don’t

capitalise on the trend and re-instate our position of being the number

one exporter in USD terms.

Colonial roots

Established in the era of British colonisation, Sri Lanka’s plantations

experienced a period of progress with the agrarian elite investing in

bank institutions, infrastructure, railways, credit expansion and

industrialisation. The money earned from tea and later rubber exports

was the essential capital that would bring about important changes in

the country’s society, economy and culture.

However, living and working conditions of the bonded estate labour was

not a consideration and the feudal hierarchy lorded over them ensuring

productivity, quality, and profit above all. Basic necessities like

healthcare, housing and education were limited to the basic

requirements. Plantations were run tightly, in order to maintain the

lowest cost of production and highest rates of productivity and soon

Ceylon tea began to be recognised and consumed the world over.

When Sri Lanka gained its independence, the management of the country’s

plantation industry was still retained in private companies known as

Rupee and Sterling companies. While the British no longer retained

sovereignty over the island, there was a substantial continuity in terms

of how the island’s plantations were operated and managed.

During the pre-nationalisation period, Agency Houses on behalf of them

managed approximately 134,000 hectares of tea alone with rubber

occupying 64,000 ha and coconut, 22,000 ha, all of which covered 8% of

the Country’s land with their continuing performance instrumental in the

preliminary establishment of Ceylon tea’s reputation for the highest

quality.

The nationalisation debacle

During the 1972–1973 periods, the Government of Sri Lanka nationalised

privately-owned estates, taking over some 502 privately-held tea, rubber

and coconut estates, due to socialist ideologies that led to major land

reforms, limiting the extents that could be privately held. In 1975 the

Rupee and Sterling companies were nationalised – with Agency Houses

continuing as trustees. Thereafter in 1976, these were turned over to

the two largest State-owned plantation agencies, namely: Janatha Estates

Development Board (JEDB) and State Plantations Corporation (SPC).

Several smaller entities such as Usawasama, Janawasa, were also created

and stacked with political appointees who mismanaged the estates to an

extreme point where they had to be shut down and land distributed for

village expansion. Pulling political strings was rampant, with totally

incapable, inexperienced managers hired.

Although socialist ideologies were being rammed into the system’s

administration, the plight of estate workers was yet to be factored in.

Rather, the debates surrounding nationalisation were almost purely

motivated by a desire to take control of significant profit generating

resources, ply it with political sycophants and distribute land in a

sweeping, authoritarian manner. Estates began to degenerate rapidly

under State management, while the numbers employed in these estates

ballooned in size with the country’s political class increasingly

viewing the sector as a job bank to purchase support each election

cycle.

This reality was plainly understood even at the time, as evidenced by

academic publications from the era. An excerpt from an American

publication in 1992 noted: “The privatisation initiative in the tea

sector as part of structural adjustment programmes advocated by the

World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is intended to

balance the national budget by removing Government subsidies and

privatising State enterprises such as JEDB and SLSPC. Theoretically this

policy initiative may generate more efficiency and equity in the Sri

Lankan tea economy”.

“Public funds which were previously used in subsidising inefficient

bureaucratic agencies can now be reallocated for the purpose of much

needed infrastructure and human development programmes. Moreover, the

management of privatised entities may have the choice to operate free of

political interference and financial regulations of the Government.”

(Economic Rationale for the Privatisation of Tea Plantations in Sri

Lanka by Dr. Patrick Mendis, 1992)

All official records and high powered government committees have

confirmed that by the time the estates were handed over to the RPCs,

post privatisation in 1995 that “the State-run plantations continued to

make heavy losses and performed poorly throughout most of its

existence”.

Overstaffed, underperforming and riddled with debt that was ultimately

costing the Sri Lankan tax payer approximately Rs. 400 million per

month, there was only one lesson that ultimately came out of the 20

years of nationalised management of Sri Lanka’s plantation sector,

namely that politicisation breeds inefficiency, especially when mixed

with complex businesses. From this era the positive contributions that

did come about were the result of World Bank funding which was directed

towards much needed replanting, factory development and transport

vehicles.

By the time privatisation was completed in 1992, conditions on the

estates had reached their lowest point. Considering the continuous

losses and increasing debts of JEDB and SLSPC up to the time of RPC’s

and private management from 1992 onwards, it is very likely that they

would have continued to make losses and incur Government financial

support. If privatisation had not taken place, the Rs. 1.5 billion per

year financial support provided by the Government to the JEDB/SLSPC in

1992, would in today’s Rupee amount to almost 12 billion per year.

The political upheavals during the 1970s and 1980s were sharply felt by

estate communities and the plantation industry as a whole. Our industry

has endured through the severe weathering effects caused by the ensuing

conflicts including the 1970s and ’80s JVP insurgency when many young

college students were forced to take refuge in hill country estates.

This in turn resulted in the estates becoming easy targets for violent

police raids with estate management being hounded by the insurgents in

turn. The situation became grave when planting executives on duty were

brutally murdered in the remote plantations. Talented estate managers

migrated overseas with many of their competent peers leaving in disgust

at the senseless violence.

The conflict with the LTTE also took its toll on the industry and estate

communities with several thousand estate workers seeking refuge in

South India with racial discrimination levelled against them. The scars

of decades of ethnic conflicts are still clearly felt today,

contributing to the mass exodus of the more productive estate staff and

workers, leading to a depleted work-force, faced today.

Adapting on-the-go: The era of privatised management

Once the inability of the State to manage the plantations had finally

manifested, privatisation emerged as the only possible alternative to

the collapse of the industry and offer-for-sale documents were prepared

to serve as the legal foundation for privatisation. These documents,

executed by the State, provided each RPC complete freedom to use the

leased land for diversification into any other crop, extraction of

minerals, forestry and timber harvesting and setting up of any venture

permitted by law.

The overarching provisions and terms of these documents hinged on the

promise of complete autonomy for the private sector to manage their

plantations in the most efficient and productive ways possible and this

was the very reason for estates to attract strong interest, both locally

and internationally. Unfortunately for our industry, neither the offer

document nor the spirit of these initial agreements was respected by any

subsequent Governments. Such a resounding failure on the part of

successive Governments has been the source of continuous and severe

disruption to many development plans for RPCs.

The plantation companies were bequeathed a total land extent of 239,398

ha – comprising of 94,244 ha of tea land and 57,930 ha of rubber land at

the time of privatisation in 1992. In the 23 years since, politically

motivated acquisitions and illegal encroachment resulted in a 28.2%

reduction in the most productive land extents – including a 16.3%

reduction in tea land and a 25.8% reduction in rubber lands – shrinking

total RPC land extent down to 180,291 ha by 2016.

The main aim of privatisation was to improve the overall managerial

performance and in just over a quarter century later, the plantation

sector has showed drastic improvements across many indicators, be they

economic, social or environmental.

Significant investments were made by shareholders in the 1995/96

privatisation era, based on the several opportunities laid out in the

bid document. These included agri-diversification, forestry, the setting

up of hydro-power projects, and total autonomy on how the land should

be best utilised.

Post privatisation, salaries of estate staff increased with employees

confirming that there were more opportunities for promotions linked to

performance rather than political connections and influence. Previous

insecurities present in State-owned plantations, where political

affiliation and influence determined employee security, were tempered

down, as a performance-based culture was instilled by the new

management.

Weathering all storms and hurdles, along with ad-hoc policy decisions

detrimental to best agri-practices, the 2016 edition of world fact book

on exports and commodities, stated Sri Lanka as second in total USD

worth of exported tea, next to China. China at $ 1.5 billion commands

22.8% of total tea exports, Sri Lanka: $ 1.3 billion – 19.2%, Kenya:

$680.6 million at 10.4%, India: $ 661.7 million at 10.1% and United Arab

Emirates, the newest entrant that does not grow any tea: $ 287.9

million at 4.4%.

While Kenya has beaten Sri Lanka as the biggest tea exporter, Sri Lanka

continues to maintain its position as the world’s highest tea exports

revenue earner, losing its number one position to Kenya as the highest

exporter in the world a few years ago. Notably, Sri Lanka also remains

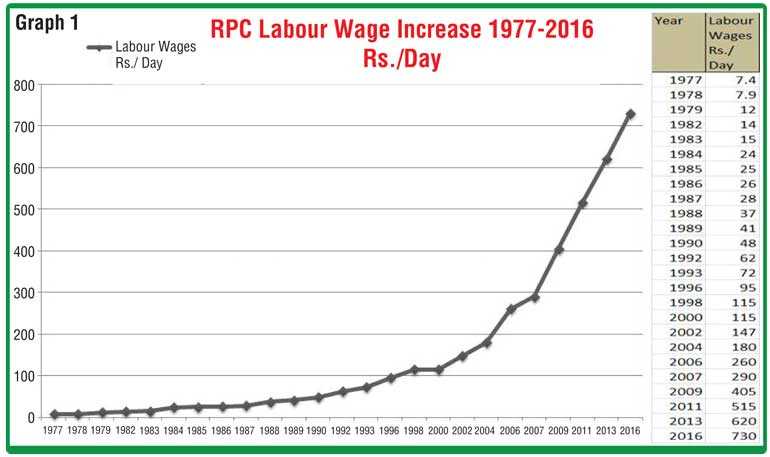

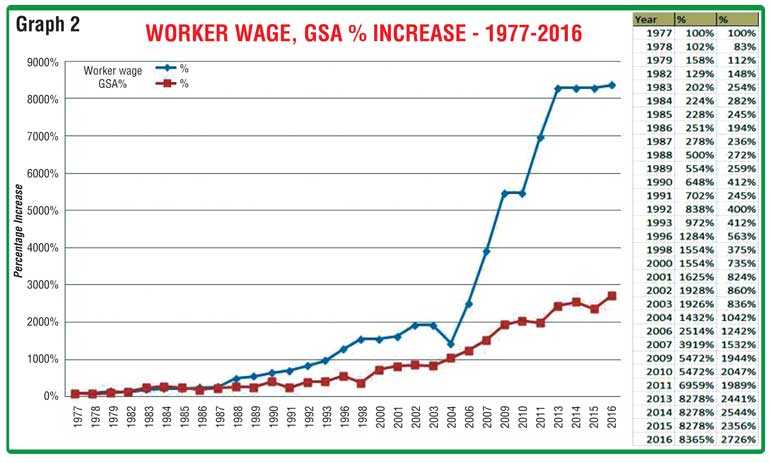

as the most expensive tea producing nation in the world, with average

wages having steadily increased, at a rate higher than the General Sales

Average of Pure Ceylon Tea in international markets.

Facing severe encroachments, a shrinking labour force, and the

periodical obstacles created by Government policy interventions, RPC tea

production reduced to 72.9 million kg, but the yield per hectare

improved to 1,138 kg per ha in 2016, as compared with 1,021 kg per ha in

1992. However with another ad hoc decision of the Glyphosate ban since

March 2015 the YPH dropped to 900 by end March 2017.

At this point, it must be mentioned that the glyphosate ban, a decision

made on a whim, with no scientific evidence to justify such a drastic

action has caused a total colossal loss of Rs. 35 b to the industry

while the Country risks losing a longstanding, lucrative export market

in Japan.

Meanwhile, rubber YPH has recorded a sharp increase from 647.3 kg per ha

in 1992 to 862 kg per ha in 2016. Since 1992 the RPCs have replanted

vast extents, at times exceeding the average 3% replanting per annum.

The

RPCs strategic forward planning saw the need for diversification within

a short period which prompted many RPCs to diversify in to another

major crop oil palm in the best suitable areas. Mitigating total

dependency on tea and rubber, factoring in shortage of workers was the

strategic decision for oil palm – justifiably so, given that the

financial performance of oil palm during the period 2013 to 2016, a

tenure in which both tea and rubber prices crashed. Oil palm companies

set up processing mills with their own funding which has saved the

national economy valuable foreign exchange by curtailing edible oil

importation.

The

RPCs strategic forward planning saw the need for diversification within

a short period which prompted many RPCs to diversify in to another

major crop oil palm in the best suitable areas. Mitigating total

dependency on tea and rubber, factoring in shortage of workers was the

strategic decision for oil palm – justifiably so, given that the

financial performance of oil palm during the period 2013 to 2016, a

tenure in which both tea and rubber prices crashed. Oil palm companies

set up processing mills with their own funding which has saved the

national economy valuable foreign exchange by curtailing edible oil

importation.

Today, it is the RPCs which are leading the charge on crop

diversification, with upwards of 2,300 hectares of RPC land now under

diversification on crops other than oil palm.

The oil palm plantation industry is also facing turmoil with a temporary

ban being enforced for the cultivation, based on emotional agitation by

some groups with vested interests, sharply interrupting an entire

development programme. Plants to the value of almost Rs. 400 m

propagated with imported seeds with the necessary government approval is

currently running the risk of being destroyed if they are not planted

at the correct time.

Large-scale diversifications of innovative crops include arecanut,

macadamia, pineapple, rambutan, soursop, lemon, oranges, papaya,

avocado, passion fruit, pears, and vanilla together with spices like

pepper, cloves, cardamom, and forestry initiatives from khaya, giant

bamboo and other fuel-wood plantations.

Meanwhile, the 36 State-managed estates which were also managed by the

same JEDB and SLSPC during the nationalised era remain a horrendous

burden on taxpayers, being in arrears of close to Rs. 3 billion on their

statutory dues of EPF, ETF and Gratuity and the Government continues to

subsidise them to the tune of Rs. 1.5 billion a year. Here, the State

has ample opportunity to turn its attention to the massive loss making

State-managed plantations and implement so called ‘alternative models’.

Government and stakeholders must clearly understand that plantations

cannot be managed in the historical manner given the current political,

environmental and economic issues and continue to be viable business

entities. Provisions for changes are available in the lease document and

RPCs must be given a free hand to exercise the rights without

interference and subsequent directives which interrupt the development

programmes. Each RPC has a business plan based on indicators such as

location of the plantations, crop mix, availability of workers and

several factors which are not common across all plantations.

In the spirit of a privatised plantation sector

RPCs have invested a cumulative Rs. 70 billion between 1992 and 2016,

contributing seven billion in lease rentals and a further 1.72 billion

in income tax, coupled with dividends to Sri Lankan shareholders,

totalling Rs. 8.17 billion, despite continuing challenges from

diminishing availability of labour, incessant increases in labour wages

not linked to productivity. The emergence of competitors like Kenya,

operating on significantly larger economies of scale to produce volumes

of tea, at drastically lower costs of production poses a big risk.

In addition to the clear superiority of RPC management in terms of

productivity, it has only been under our stewardship that more

uncompromising, environmental protection standards have been adopted.

These include Rainforest Alliance certifications secured only upon the

completion of a stringent process of auditing and the implementation of

extensive environmental safeguards. To date most RPCs have secured the

Green Frog seal of compliance propelling them to the prestigious Global

Sustainable Agriculture Network standard.

Similar efforts have been channelled towards forest conservation and

rehabilitation, with the majority of RPCs certified with the Forest

Stewardship Council. Membership requires organisations to develop

national forestry standards, localised to meet the unique requirements

of each natural habitat, as per global standards.

To-date RPCs have cultivated in excess of 20,000 ha of forestry.

We wish to recognise and thank the Governmental authorities for

commencement of guidelines towards a national policy for commercial

forestry, on a request by the Planters’ Association. Despite a five-year

forestry plan in place, a sudden ban, imposed five years ago on felling

timber which is grown for fuel wood, meant that estates had to

transport their requirement of fuel wood at an additional cost, causing

additional and unnecessary burden on the bottom-line.

At present, there are 688 International certifications for 297 RPC

factories including HACCP, ISO 22000, Fair Trade, Forest Stewardship

Certification (FSC) ISO 9000, Care Quality Commission (CQC), Ethical Tea

Partnership (ETP), UTZ, Rainforest Alliance (RA), Global GAP, SA etc.,

thereby ensuring the maintenance of extremely strict production and

processing standards that ensure the safety of consumers, workers and

the wider environment.

Furthermore, the ‘Ceylon Tea’ image and the branding of Food Factory

Concept, Chemical Free Tea, Cleanest Tea in the world, Ethically Managed

Plantations, Zero Child Employment, Ozone Friendly Tea, Sustainable

Agriculture, Product Traceability to Source and Single Origin Estate

Marks are predominantly RPC standards which is a huge plus for the image

of Ceylon Tea and its branding.

Other internationally-accepted certifications which entail rigorous

compliances with environmental, agricultural, economic and social

standards of conduct, obtained by RPCs include Good Manufacturing

Practices (GMP) for Rubber and Cinnamon processing, Global Organic Latex

Standard, for rubber ISO 9001:2008 Quality Management Systems

Certification, for Oil Palm & Fruits, while the Round Table on

Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) certification is work in progress.

To-date not a single estate worker has been laid off; instead, their

opportunities have increased with the productivity linked clause

attached to their daily wage. Living conditions have improved vastly

with two-bedroom houses with en-suite toilets built to replace the line

rooms. A total of 50,000 such homes have been built in an ongoing effort

for the 180,000 families that still live on RPC estates – all of whom

may not be actually working in the fields.

From schools to hospitals, crèches to retirement homes, ongoing welfare

activity to one-tenth of the country’s population is a priority of the

RPCs which constitute the Plantations Human Development Trust (PHDT)

along with trade unions and Government. Today an estate worker has the

ability to earn in excess of Rs. 25,000 per month, in addition to all

other infrastructure facilities provided by RPCs.

The true strengths of Sri Lanka’s plantation industry and their source

In light of these and many other achievements by the RPCs, standards of

Sri Lanka’s plantations have been elevated far beyond its difficult past

and therefore we assert that in truth, many of the strengths that

remain in our industry today are initiatives taken by the RPCs.

Environmental protection and quality standards have been implemented

across the RPC sectors, where none were in place before privatisation.

Our produce continues to fetch favourable – and often times record

breaking prices from international buyers.

To say that worker wages have been increased periodically is an

understatement. Wage increments have been awarded not commensurate with

productivity, politically prodded and not considering the

competitiveness of the company. Holding back wage increments was never

the RPC agenda; however linking it to productivity will be the future of

the plantation industry in Sri Lanka.

Despite constant politically motivated interference, many RPCs have

commenced investments into crop diversification in order to consolidate

revenue streams, even when various Governments have continued to

vacillate on vital policies such as the importation of seed material.

Meanwhile, important progress is being made to emulate the successful

examples of RPCs who have partnered with large conglomerates to enter

into value addition; something which did not exist during the time of

State management.

Diversification through tea tourism is hugely successful. These include

tea factory tours, hotels and niche luxury tea trails experiences

–attracting high-spending tourists from across the globe – helping to

further raise the profile of the island as a vibrant tourist

destination. Many others are working on investments into this sector

with the Planter’s Association committed to supporting the relentless

exploration of innovative diversifications.

Favourable policies that will look at the industry 50 years from now and

start sowing the seeds to propel it to a future-ready, economic power

base, is the need of the hour. As an industry we cannot afford any more

random ad-hoc policy decisions. Extending leases is an economic

imperative, given crop cycles of rubber and oil palm. RPCs must be

assured that leased land will not be annexed or encroached through

political heavy handedness.

Ultimately, the RPCs each need to be allowed to draw upon their precious

experience gained from the last quarter century of management, in a

rapidly changing environment, to autonomously decide on the best course

of action for each company, in alignment with a common ethic of

sustainable, profitable, diversified plantations.

(The writer is Chairman, Planters’ Association of Ceylon.)