A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Sunday, December 29, 2019

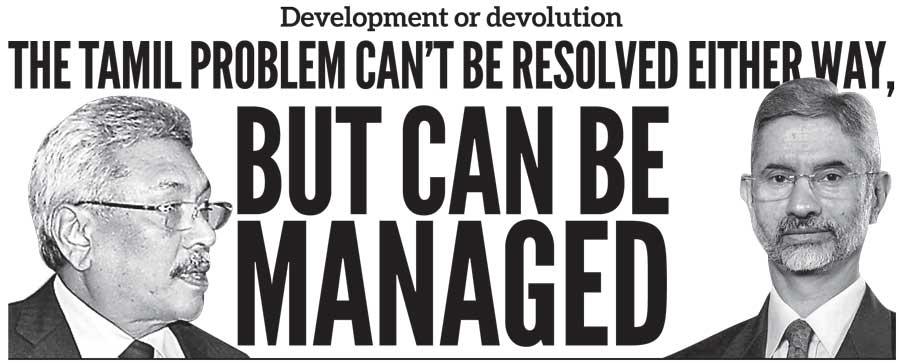

The Tamil problem can’t be resolved either way, but can be managed

Development or devolution

It seems that President Gotabaya Rajapaksa intends to replace power devolution, a persistent Tamil demand, with development.

It seems that President Gotabaya Rajapaksa intends to replace power devolution, a persistent Tamil demand, with development.

“Devolution of power is a lie and most are opposed to it,” he told a

meeting of heads of media organizations recently adding that

‘reconciliation can be achieved through broad development’.

He had echoed the same sentiments previously, at a meeting with Indian

External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and in at least two

media interviews.

media interviews.

In an interview with Suhasini Haider of the Hindu during his official

visit to New Delhi, President Gotabaya said: “For 70 odd years,

successive leaders have promised one single thing; devolution,

devolution, devolution. But ultimately nothing happened. Full devolution

of powers as promised by the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1987

could not be implemented “against the wishes and feelings of the

majority [Sinhala] community.”

The Tamil political elites had not done much to alleviate the effects of economic deprivation caused by three decades of war, after they were handed power

He added: “No Sinhalese will say, don’t develop the area, or don’t give jobs, but political issues are different.”

This appears to be the de-facto position of the government. It would

become its official position after the General election, (the result of

which is not too difficult to guess).

But, how effective will development be as a solution to the ethnic question though?

But, how effective will development be as a solution to the ethnic question though?

Few commentators have cast doubts on the efficacy of the presidential remedy.

As M.S.M. Ayub had written in these pages last week, “The notion that a

higher degree of devolution will solve the issues facing Tamils is in

their blood.”

Elsewhere, Prof Ameer Ali surmises, “Even if economic inclusion allows

minorities to prosper, it does not mean that minorities, and especially

the Tamil minority, would like to remain politically excluded. It is

economic prosperity that enables people everywhere to rise up and demand

participation in governance”.

Though his temptation in the article to blame the Sinhalese for

everything wrong in the country feeds into polarization and makes it a

partisan reading, Prof Ali nonetheless

has a point.

has a point.

Development as a stand-alone solution would not work. Probably, it would make things worse and skew the current status quo.

That is because it overlooks the elephant in the room of all causes. The

Tamil political struggle was not so much about discrimination or

economic deprivation -- these maladies came to define the Northern life

only after the Tamil leadership unleashed a suicidal madness that

cannibalized its own children and then bombed the rest of the country.

Tamil political struggle has always been about political aspirations

emanating from Dravidian/ Tamil nationalism. These aspirations were

subsequently repackaged as grievances for ease of sale to the receptive

audience. Nonetheless, in its essense, Tamil nationalist struggle is for

a separate nation in the North East, identified as Tamil homeland and

entitled to self-determination. Understandably enough, the Sinhalese

majority have historically viewed these aspirations as incompatible with

national interests. That the Tamil elites who advanced those goals

resorted to India to ‘intimidate’ Colombo, and that they, at best, had

split loyalties did not inspire public confidence.

Exactly due to the socio-cultural dynamism of Dravidian civilization,

which stands for a Tamil exceptionalism, Sri Lankan Tamil elites had a

problem with coming to terms with the demographic reality in the

country, long before it received independence. Northern elites boycotted

the first State Council elections in 1932. Though the Gandhian youth

who pioneered the boycott called for full independence, cannier Tamil

political elites had less noble grievances of losing their traditional

privileges to a larger Sinhalese population who were empowered by the

universal suffrage introduced under the recommendations of the

Donoughmore Commission.

It was the same calculations that were behind G.G. Ponnambalam’s 50-50 proposal.

Those demands grew in intensity long before the Sinhala Only Act, though

the latter itself contributed to the hardening of the Tamil position.

Throughout the past 70 years, the mainstream Tamil leadership eschewed

national politics or responsibilities in the government. Though the

contemporary TNA leadership had shown a lot more maturity than their

over-hyped predecessors.

This political behaviour should be contrasted with that of other

minorities, Muslims and Tamils of Indian Origin, whose leaders have

always opted for a role in the Central government and also to

incrementally advance the positions of their communities.

Economic deprivation, if any, was hardly a factor in the Tamil nationalist campaign.

When Jaffna erupted in ethnic rage and terrorism in the early 80’s, it

was the second richest city in the country. Early claims of ethnic

discrimination were indeed a political ploy aimed at mass mobilization.

In the first half of the 80s, the Chief justice, IGP, and Attorney

General were all Tamils. One-third of administrative service, lawyers,

and accountants were also Tamils.

The Tamil political elites had not done much to alleviate the effects of

economic deprivation caused by three decades of war, after they were

handed power.

When the provincial councils in the North and the East finally came into

being after a long delay, much energy was wasted, especially in the

Northern assembly to advance rhetorical partisan agendas. Regional

development was never a priority.

Would development and economic prosperity assuage the cry of Tamil nationalism?

Probably not. Take for instance the ethno-nationalism in the rich world.

Catalonia is the richest province of Spain and is accorded with

enhanced devolution of power, yet it still voted for independence in an

unofficial referendum. Elsewhere, Scottish nationalists are

contemplating a second referendum for independence.

Whereas, relative economic deprivation could even serve as a monetary

deterrent for the worst of ethnic nationalist mobilization, though that

as a solution is immoral and can have dangerous side effects however,

any effort to cultivate economic inter-dependency between the North and

Tamil Nadu, at the expense of Colombo would be a recipe for a long

term disaster.

term disaster.

Then, would devolution be the solution? A better question would be how

much of devolution is the solution? Given the historical tendency of

Tamil nationalism, an all-out devolution, including land and police

powers could more likely unleash an era of confrontation with the Centre

than cooperation. And perceived grievances emanating from that

confrontation would then be used to public mobilization, leading to a

spiral of nationalist rage on both sides.

The unpalatable truth is that intractable problems like Sri Lanka’s

Tamil problem can not be resolved. But they can be managed.

Therefore the emphasis should be the management of the problem to

prevent it from becoming a distraction from other national priorities or

a looming national security threat.

Countries as wide-ranging as Turkey, Russia and Singapore have done that, some with an iron fist, others with a velvet glove on it.

Countries as wide-ranging as Turkey, Russia and Singapore have done that, some with an iron fist, others with a velvet glove on it.

Sri Lanka should find its mixture of strategies. Development is, of

course, part of it. So is a degree of devolution that is not designed to

undermine the Centre. Rule of the law should be empowered. Language

rights of Tamil speakers, enshrined in the Constitution, should be given

their practical expression, Deficiencies there lie in administrative

measures.

However, there is more to this. If there is a carrot, there has to be a

stick. Security forces and intelligence agencies would have a role in

keeping a tab so that, relative freedoms would not be used to mobilize a

new phase of suicide terrorism. At the moment, it is the collective

appreciation of the insurmountable loss of the previous misadventure

that serves as the biggest deterrent against the revival of the worst

forms of Tamil nationalism. Any alternative that replaces the current

status quo should not skew it.

Follow @RangaJayasuriya on Twitter