A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Friday, January 24, 2020

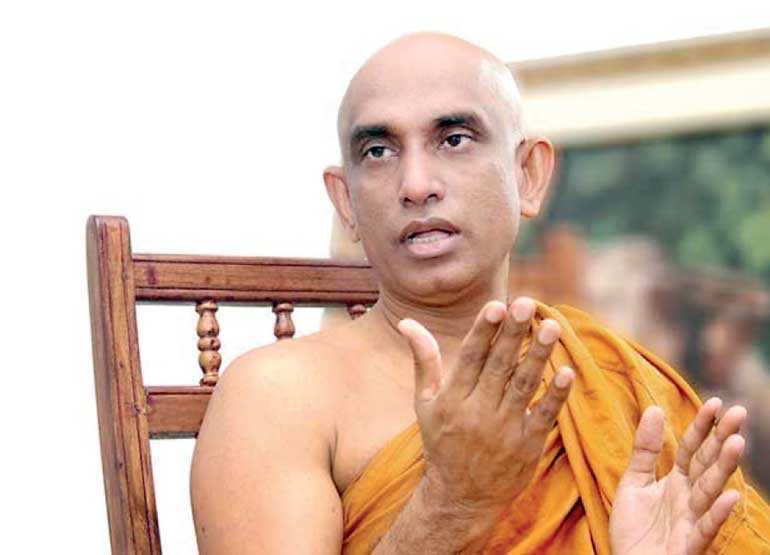

Our heritage is Kandyan law; not Roman Dutch law as Rathana Thero thinks

If

Rathana Thero wants to uphold Sinhala Buddhist culture, what he should

do is to repeal the Marriage Registrations Ordinance 19 of 1907 and make

the Marriage and Divorce (Kandyan) Act 44 of 1952 the Common law of Sri

Lanka in relation to marriage and divorce

There were four bills presented by private members to the Parliament on 8

January (one bill is to be presented) which were already advertised in

the gazette. They were to repeal the Kandyan Marriage and Divorce Act

No. 44 of 1952; to repeal the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act No. 13 of

1951; to amend the Marriages (General) Ordinance No. 19 of 1907; to

amend the Marriages Registration Ordinance; and to introduce a minimum

age of marriage in Sri Lanka. The first three were/will be presented to

the Parliament by Ven. Athuraliye Rathana Thero MP and the other two

were presented by MP Dr. Thusitha Wijemanna.

In Sri Lanka the Common law applicable to marriage and divorce is based

on the Roman Dutch law. This Common law is in the Marriages (General)

Ordinance No. 19 of 1907. In addition to that there is Kandyan Marriage

and Divorce Act No. 44 of 1952 applicable for the people living in the

Kandyan Districts. For the Muslims in Sri Lanka the applicable law is

Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act No. 13 of 1951 (MMDA). The intention of

the proposed amendments is to make Roman Dutch law the only law

applicable to marriage and divorce in Sri Lanka and to make the minimum

age for marriage 18 years.

Minimum age of marriage

According to Section 23 of MMDA, a marriage contracted by a Muslim girl

who has not attained the age of 12 shall not be registered under this

Act unless the Quazi for the area in which the girl resides has, after

such inquiry as he may deem necessary, authorised the registration of

marriage. According to Section 15 of Marriage Registrations Ordinance 19

of 1907, lawful age of marriage, in relation to a male was 16 years and

in relation to a female was 12 years and if a female was a daughter of

European or Burgher parents, the minimum age was 14 years. It was

amended by Act No. 18 of 1995 raising the minimum age of both male and

female to 18 years irrespective of the ethnicity.

According to Section 66 of the Marriage and Divorce (Kandyan) Act 44 of

1952, lawful age of marriage, in relation to a male was 16 years and in

relation to a female was 12 years. This was amended by Act No. 19 of

1995 raising the minimum age of both male and female to 18 years.

Therefore, not only the Muslims but also all the others thought in the

same line in relation to the minimum age of the marriage. All the

others, other than Muslims, changed it. The Muslim community should also

fall in line with the changing environment.

Kandyan law

At the time of the arrival of the Western invaders to Sri Lanka, the

marriage and divorce practices and the relevant law were very liberal.

According to Niti Nighanduwa which was believed to be written between

1769 and 1815 at Senkadagalapura, either the husband or the wife can

disengage from the marriage bond. There were no barriers for

disengagement. However, there were consequences.

At the marriage the ownership of the properties of the husband and wife

were kept separately with them. The wealth earned by both would be

divided equally at the time of disengagement. If the disengagement of

the marriage is executed by one party, then that party does not have any

right of the assets of the other party.

Niti Nighanduwa gives a detailed account of the family law prevalent

during that time. Liberal nature of that law was confirmed by Robert

Knox in his book.

According to Section 32, the dissolution of the marriage can be granted on any of the following grounds:

- Adultery by the wife after marriage

- Adultery by the husband coupled with incest or gross cruelty

- Complete and continued desertion by the wife for two years

- Complete and continued desertion by the husband for two years

- Inability to live happily together, of which actual separation from bed and board for a period of one year shall be the test

- Mutual consent

These provisions although liberal tried to impose conditions to the provisions in Niti Nighanduwa.

Roman Dutch law

Colonial masters imposed a different law based on Roman Dutch law on

marriages and divorces for the people who lived outside of the Kandyan

districts. These people were influenced and “cultured” by their colonial

masters over centuries. Marriage was viewed as a sacred act by the

Christians.

Christian marriage is a union between a man and a woman, instituted and

ordained by God, for the lifelong relationship between one man as

husband and one woman as wife. This expectation of the lifelong

relationship was being reflected in the Roman Dutch divorce law.

Law makers should never interfere with Muslim law which is based on their cultural heritage. People should oppose the Muslim law if there are any violations of human rights or any discrimination against the weak in the name of such culture and laws. If Rathana Thero wants to have a one law for marriage and divorce, he should draft a new law applicable to current society eliminating the destructive aspects of Roman Dutch law

According to Section 19 of Marriage Registrations Ordinance 19 of 1907,

no marriage shall be dissolved during the lifetime of the parties except

by judgement of divorce a vinculo matrimonii pronounced in some

competent court. Such judgement shall be founded either on the ground of

adultery subsequent to marriage or of malicious desertion or of

incurable impotency at the time of such marriage.

This is legalisation of the will of the God. This conservative law was

based on the Victorian culture that prevailed in Europe at that time.

Present divorce laws in the Europe are very liberal and are in line of

the Kandyan law. Present Sinhala society is also in the process of

absorbing old Kandyan values of marriages and divorces.

Rathana Thero and his ideological group of Sinhala Buddhism are

unknowingly trying to uphold a law which is based on colonial Christian

values while trying to abandon a law which is based on Sinhala Buddhist

heritage and the values. What an irony.

If Rathana Thero wants to uphold Sinhala Buddhist culture, what he

should do is to repeal the Marriage Registrations Ordinance 19 of 1907

and make the Marriage and Divorce (Kandyan) Act 44 of 1952 the Common

law of Sri Lanka in relation to marriage and divorce.

Muslim law

In Sri Lanka the amendments to MMDA were discussed. Muslim women have

been agitating against the provisions of the Act for more than 30 years.

Successive governments appointed different committees. A committee

headed by Justice Saleem Marsoof was appointed in 2009 and the report

was issued in July 2019. Although Muslim Parliamentarians agreed to 14

recommendations, it is reported that All Ceylon Jamiyyathul Ulama (ACJU)

was against these recommendations.

Muslim women request that the minimum age of marriage for all Muslims

must be 18 years without any exceptions; women should be eligible to be

appointed as Quazis, as Members of the Board of Quazis, Marriage

Registrars, and Assessors (jurors); the MMDA must apply uniformly to all

Muslims without causing disadvantage to persons based on sect or

madhab; signature or thumbprint of bride and groom is mandatory in all

official marriage documentation to signify consent; registration should

be required for legal validity of marriage; adult Muslim women are

entitled to equal autonomy and need not require ‘permission’ by law of

any male relative or Quazi to enter into a marriage; Talaaq (divorce)

and Faskh (annulment) rights between women and men must be equal;

procedures for divorce initiated by men and women must be the same,

including appeal process; and to revise the Quazi court system to ensure

a competent system with improved access to justice for women and men.

These are very reasonable demands. Civil society in Sri Lanka is also

opposing to MMDA in the same lines namely discrimination against

children and women. However nationalistic Sinhala Buddhists are opposed

to MMDA on the grounds that Sri Lanka should have only one law and there

should not be different laws for different ethnicities.

Therefore, the opposition to MMDA by the Muslim women and civil society

and the opposition to the same by the nationalistic Sinhala Buddhists

are coming from different reasons and from different backgrounds. The

latter, although comes with the frontline of ‘one country, one law’ in

the pretext of unification, is in fact targeting discrimination on the

Muslims.

Conclusion

Law reflects the culture of the people. Muslims in Sri Lanka over

centuries preserved their cultural identity while mixing with the other

communities.

In her book ‘The Muslims of Sri Lanka – One Thousand Years of Ethnic

Harmony, 900-1915,’ Lorna Dewaraja stated as follows: “...This is

striking example of the policy of live-and-let-live characteristic of

Sinhala society at that time. Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists were

voluntary participants in the festivities of the Embekke devala and none

of those groups lost their cultural identity in the process.”

Law makers should never interfere with Muslim law which is based on

their cultural heritage. People should oppose the Muslim law if there

are any violations of human rights or any discrimination against the

weak in the name of such culture and laws. If Rathana Thero wants to

have a one law for marriage and divorce, he should draft a new law

applicable to current society eliminating the destructive aspects of

Roman Dutch law.