A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Tuesday, May 5, 2020

Strategic role of skills improvement in human capital development

Sri Lankan industries are still unable to meet their skills

requirements. Even though Sri Lanka is currently struggling to overcome

high levels of unemployment, some employers in some sectors are

reporting skill shortages.

Sri Lankan enterprises are expected to face a growing number of

hard-to-fill vacancies due to skills shortage in most economies.

Shortages, unemployment and skill mismatch have negative financial and

non-monetary consequences for employers, individuals, and society as a

whole. It is vital that not only is the Government able to remedy this

situation, but also that private sector skilled training institutions

should take collaborative actions on it.

Many unemployed young people in our country are struggling to find job,

but the common obstacle we see here is the lack of skills requested by

industries. Therefore, the article highlights that the creation of a

skilled workforce in the future will be the catalyst for the country’s

rapid growth.

The world doesn’t remain the same every day. It keeps on changing. Every

day, we come across new developments which may be technological,

process improvements, newer ideas, products and so on and thus business

environment is facing considerable changes (Heraty, 1999).

The day-to-day new technological changes demand new talented/skilled

employees in this new era. The continuous shortage of those skilled

workers remains a weakness to our human capital development. Therefore,

if we are to make our human prosperous, we need to start new strategies

for skills development programs in our country to meet the talent

requirements of industries.

Labour force participation in Sri Lanka has historically been low with

only about a half of the eligible people between the ages of 15 and

above offering their services to the market. While the male

participation has been around 72%, the female participation has been low

at about 35%. Of them, the youth consisting of those between the ages

of 25 and 40 have been the largest segment in the labour force, making

up of almost the entirety of the people in that age group. Hence, if

they leave the country, it is considered a severe loss to the economy

(W.J. Wijewardana, 13 May 2019).

Introduction

“Human capital” is becoming a major term in development sectors. The

quality of human capital determines the productivity and, ultimately,

the growth and development of enterprises. Human capital—defined as the

“stock of economically productive human capabilities”1 — encompasses

knowledge, health, skills, entrepreneurial talent, determination and

other human traits that lead to success in endeavours.

Human capital is obtained through general education and is transferable

from one enterprise/endeavour to another. Skills are a subset of human

capital specific to a particular task, job or enterprise and are

obtained through specialised education or training, such as carpentry or

dentistry. Human capital and skills may play different but

complementary roles in the growth and development of the private sector.

General human capital may be used to generate ideas, form a company,

and develop new products. Skills, however, are required to produce the

product/service at competitive prices.

This article examines the importance of human capital and strategies of

skills development for development of Sri Lanka. It focuses on graduates

and institutions in tertiary education, and whether these institutions

are responsive to changes in knowledge, labour markets, and economic

development. Knowledge and skills are central not only to make labour

and capital more productive, but also to technical progress-the major

source of private sector development and sustained growth.

It also examines why the private sector suffers from skill shortages

when unemployment is high among graduates, and the policies that can

successfully address Sri Lanka’s skills gap. It concludes that in the

short run, human capital development should focus on providing short,

practical courses to secondary and higher education graduates involving

primarily on-the-job training. In the long run, there is a need to

change the way students are trained, including curriculum reforms that

favour science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Emphasis

should also be placed on critical thinking, problem solving, discovery,

and experiential pedagogy rather than rote learning.

Current status of human capital and skills in Sri Lanka

Challenges in education

Annually about 150,000 adolescents and youth join the labour force with

low skills or no skills at all, which is the biggest challenge in Sri

Lanka. With this background, in South Asia, Sri Lanka has the highest

literacy rate, yet it is unable to develop the fundamentals to create a

sustainable and a progressive education system.

Sri Lanka is also unable to retain the best brains – brain drain is a

huge issue for its development and growth. With thousands of unregulated

international schools across the country parents are forced to send

their children for the simple reason that the political establishments

are only interested in short-term policies and the inability to think

for the future and create a future ready society.

Furthermore the fundamental issues in the Sri Lankan public education

system can be cited as access to quality education, dearth of trained

teachers across the country (trained teachers are usually provided

mostly to elite schools), lack of Government funding for education, no

future focus, serving their own political interest, and an unregulated

education system.

Sri Lanka’s public investment in education is much less than the average

of 4% spent by lower middle income countries. Since the public sector

is the main provider of university education in Sri Lanka, the limited

public resources for tertiary education is a main constraint for

expanding opportunities for university education in the country.

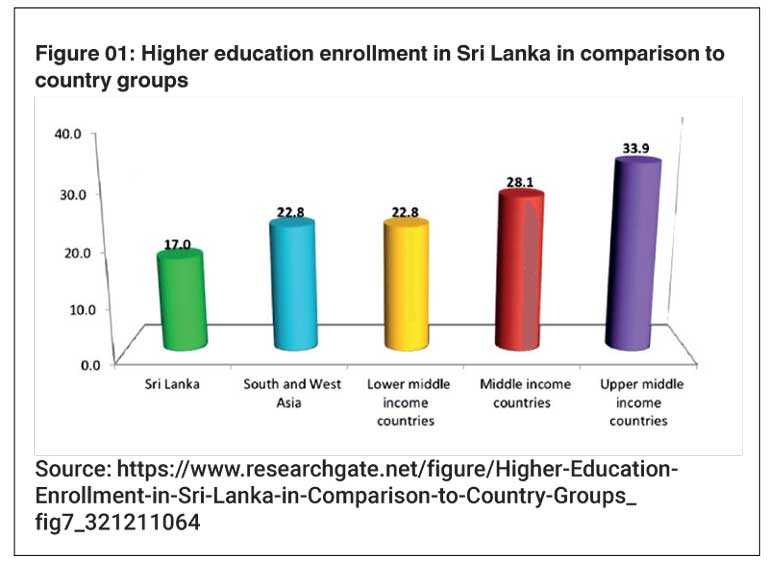

Higher education enrolment in Sri Lanka in comparison to country groups

Sri Lanka’s university admission process is highly competitive where the

students are ranked and admitted in accordance with a standardised

scoring system based on the A-Level examination results. Figure 01

emphasises comparatively very low of gross enrolment ratio at tertiary

level 17%, 24,198 (16.7%) out of 144,816 who qualified for State

university entrance.

Main challenges of the education system are lack of quality, attractive

and relevance to job market. Each year, more than 100,000 qualified

students are forced to abandon their ambition to enter a university.

Compared to other developing countries, the number of students enrolled

in tertiary education is extremely low in Sri Lanka.

Generally there is a view that universities do not have the appropriate

and updated education system for students to meet the requirement of the

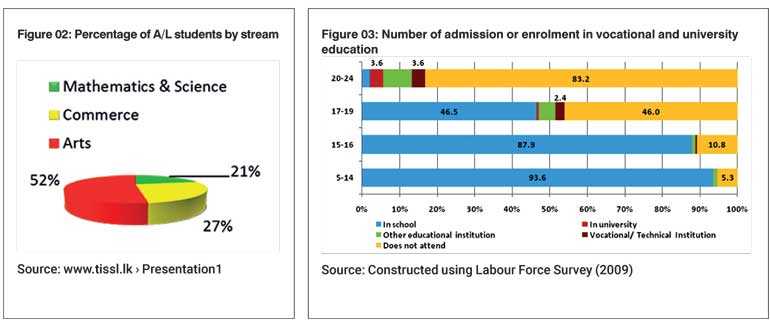

labour market. Figure 02 indicates that students are more in the arts

stream (52%) and only 21% are in the mathematics and science stream. The

other streams have more demand yet the number of enrolments is

comparatively very low.

Tertiary education enrolment

Sri Lanka needs to rapidly increase the availability of good quality and

technical skills in the labour force. The Government is aware that the

country faces serious constraints in skills development, which

jeopardises its goal of promoting a globally competitive industry.

However, this is not the case for vocational and technical skills.

The key challenge in the tertiary education that there is a mismatch in

the courses offered by higher education institutes and competencies

needed by the private sector. Major reasons for this mismatch are the

outdated curricula and the lack of interaction with the private sector

when designing degree programmes.

Figure 03 highlights that admissions or enrolments in vocational and

university education is very low among 17 to 24 years old. Enrolment in

vocational/technical institutes is only 2.4% among 17 to 19 year olds,

which shows a setback in a talent supply for the industries. Also among

the same group, about 46% do not attend any education or training

programmes.

Demand for job-specific skills is growing in Sri Lanka, which intends to

become a more competitive, middle-income country (MIC). As its economy

has grown, the composition of its gross domestic product (GDP) has begun

moving from agriculture to higher-value-added industry and services,

where jobs as machine operators, technicians, craftspeople, sales

personnel, professionals, and managers require specialised training.

The Sri Lankan Government recognises the need to increase the

employability rates of youth, a group that experienced an unemployment

rate of 20.6% in 2015. (For comparison’s sake, only about 4% of the

general population, including youth, was unemployed in 2015.) To that

end, two ministries – the Ministry of Skills Development and Vocational

Training and Ministry of Youth Affairs – are tasked with providing

technical and vocational training to prepare youth and young adults for

careers in a wide range of occupational fields. (Specific fields,

oversight authorities, and requirements are discussed below.)

To design a responsive reform agenda, policy makers need to thoroughly

understand both demand-side pressures for skills and constraints on

skills supply.

Tertiary education

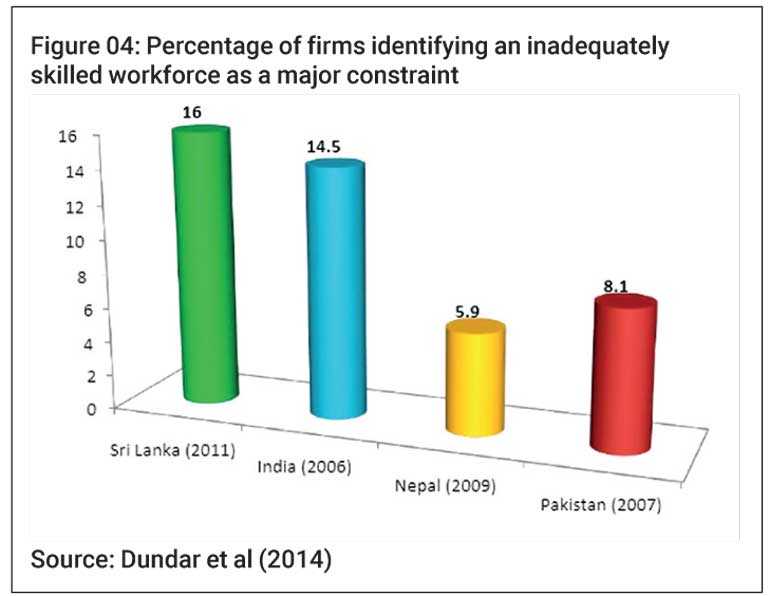

More firms in Sri Lanka identify a shortage of vocational and technical

skills as a major constraint than firms in India, Pakistan and Nepal

(Figure 04). This scarcity is exacerbated by the fact that many

well-qualified skilled individuals migrate overseas for employment,

although migration does provide a substantial source of remittance

earning. (Harsha Aturupane and Mari Shojo, 2016)

Way forward

- Increase the relevance of vocational training

- Rebrand and upgrade the quality of Technical, Vocational and Educational Training (TVET) and ensure enrolment of 40% of total 360,000 students per annum to TVET education, thereby only 10% of total students per annum fall into the unskilled labour market.

- Develop apprentices programme to attract and increase the intake to fill the requested number of employees

- To increase the relevance of the available courses in the VTA, schools and colleges.

- To design a well-articulated and clear career paths that ensures attraction and retention of talent.

- Jointly work VTA with industries to fulfil the quality delivery of skills requirement of this industry.

- To develop the action for new curriculum development with the support of industrial experts.

- To conduct an assessment of delivery and relevance of training courses and consider the relevance of industrial requirement by VTA.

- To train some trainers from experts in this field.

- To ensure to provide public relations, administration and technology courses in the training institutes.

- To establish training schools in other districts and facilitate to provide financial support to the poor students to continue these courses.

- To ensure quality, delivery, marketing and methodology in to this sector.

- Higher education

- Priorities upgrading of primary, secondary and tertiary education, and expanding enrolment in higher education so that enrolment rate is gradually increased from 17% to 50%.

- Catering for special needs among students, such (i) psycho social problems and (ii) ‘disability’ problems.

- Increasing the number of secondary schools teaching science at A/L and those teaching the technology stream

- Granting incentive allowances for teachers of English and Mathematics (secondary school level) and Science (O/L and A/L classes), based on qualifications, competence and performance.

- Meeting the recurrent costs of the Tertiary, Vocational and Professional Education sector through a ‘voucher’ system, where students who are qualified to receive this education have freedom to spend it at institutions of their choice.

- Co-ordinating all Tertiary, Vocational and Professional Education programmes, across line ministries, e.g.

Conclusion

Higher technical and vocational skills enhance the competitiveness of

economies and contribute to social inclusion, decent employment and

poverty reduction. They can open doors to economically and socially

rewarding jobs and support the development of informal businesses. These

skills can also promote the re-insertion of displaced workers and

migrants, and assist the transition to work for school drop-outs and

graduates. Developing job-related competencies among the poor, the

youth, and the vulnerable that are relevant to the private sector will

contribute to inclusive growth and poverty reduction on the continent.

Finally, the country’s prosperity depends on how many of its people are

in work and how productive they are, which in turn rests on the skills

they have and how effectively those skills are used. Skills are the

foundation of decent work. The cornerstones of a policy framework for

developing a suitably skilled workforce are: broad availability of

good-quality education as a foundation for future training; a close

matching of skills supply to the needs of enterprises and labour

markets; enabling workers and enterprises to adjust to changes in

technology and markets; and anticipating and preparing for the skills

needs of the future.

Footnotes

McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Economics 1993.

References

- https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/African%20Development%20Report%202011%20-%20Chapter%205-Human%20Capital%20and%20Skills%20Development.pdf

- http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/2018/10/22/sri-lankas-human-capital-progress-still-less-than-its-full-potential/

- https://wenr.wes.org/2017/08/education-in-sri-lanka

- http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/790661468114536058/pdf/Main-report.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275567932_Strategic_Role_of_HRD_in_Employee_Skill_Development_An_Employer_Perspective

- http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/2012/05/08/expanding-tertiary-education-is-critical-to-sri-lankas-knowledge-hub-aspirations/

- https://www.dhammikaperera.lk/

(The writer is Assistant Director, NHRDC)