A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Saturday, November 19, 2016

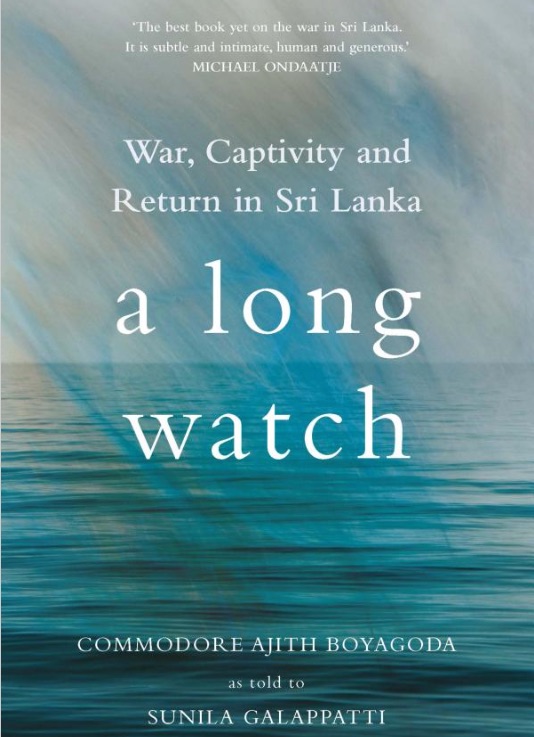

A Long Watch: War, Captivity And Return In Sri Lanka

By Charles Sarvan –November 18, 2016

A Long Watch by Commodore Ajith Boyagoda, as told to Sunila Galappatti (Hurst & Company, London, 2016)

So few know, and “those who know will be the last to tell”. (From a poem by Henry G. Lee, 1915-1945; US prisoner-of-war of the Japanese; died in captivity.)

So few know, and “those who know will be the last to tell”. (From a poem by Henry G. Lee, 1915-1945; US prisoner-of-war of the Japanese; died in captivity.)

People did not want to hear my story (Ajith Boyagoda)

Incarceration has proved productive because some individuals have

refused to accept stone walls as a prison or iron bars as a cage (lines

adapted from the poem, ‘To Althea from Prison’, by Richard Lovelace,

1617-1657) while Lord Byron in his poem, ‘The Prisoner of Chillon’,

celebrates the mind that cannot be chained. Nehru wrote Glimpses of

World History while in prison; Mandela’s autobiography which Boyagoda

read several times (perhaps A Long Watch is an echo of the title of Mandela’s book, A Long Walk to Freedom) was smuggled out of prison; the Kurdish leader Abdulla Öcalan, still in prison as I write (November 2016), published The Roots of Civilization, and Mohamedou Ould Slahi his Guantanamo Diary, reviewed by me in

Colombo Telegraph, 28 February 2016. However, A Long Watch differs in

that it is a post-prison memoir. The highest-ranking prisoner of the

LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) Boyagoda, while being watched,

watched. But “watch” is also appropriately nautical: on ships at sea,

there’s someone on watch round the clock. (The watch on the ‘Titanic’

saw the iceberg too late.)

With

disarming candour, Boyagoda writes that though he had been a sportsman

at school, he had “neglected his studies”; employment was not easy to

find, and when he joined the Navy in 1974, aged twenty, he “had no

thought of dying for my country”. (Naively, he assumed it was just

coincidence that all twelve recruited were, like him, Sinhalese

Buddhists.) On 19 September 1994, his ship was attacked and sunk, one of

the attack-boats consisting of female Black Sea-Tigers. Ironically,

being captured also meant rescue from drowning (p. 71). After spending

eight years as a prisoner-of-war, Boyagoda was exchanged for the Tiger’s

Kennedy (nom de guerre), the one who “had led a group of nine cadres in

infiltrating the Palaly air base in August 1994” (p. 190). He wryly

observes that he had been a prisoner of one of the most ruthless

terrorist organisations in the world; people talk about the Tamil Tigers

all the time; he lived with them for eight years and yet, most

strangely, no one ever wanted to hear his account (xi). I will return to

this aspect later.

With

disarming candour, Boyagoda writes that though he had been a sportsman

at school, he had “neglected his studies”; employment was not easy to

find, and when he joined the Navy in 1974, aged twenty, he “had no

thought of dying for my country”. (Naively, he assumed it was just

coincidence that all twelve recruited were, like him, Sinhalese

Buddhists.) On 19 September 1994, his ship was attacked and sunk, one of

the attack-boats consisting of female Black Sea-Tigers. Ironically,

being captured also meant rescue from drowning (p. 71). After spending

eight years as a prisoner-of-war, Boyagoda was exchanged for the Tiger’s

Kennedy (nom de guerre), the one who “had led a group of nine cadres in

infiltrating the Palaly air base in August 1994” (p. 190). He wryly

observes that he had been a prisoner of one of the most ruthless

terrorist organisations in the world; people talk about the Tamil Tigers

all the time; he lived with them for eight years and yet, most

strangely, no one ever wanted to hear his account (xi). I will return to

this aspect later.

On capture, his gold chain was taken but when he complained, it was

returned (p. 78). There was no forced-labour imposed on the prisoners.

“LTTE paramedics came to see us every day. Yes, every day, in every

place we were held” (p. 128). Food parcels sent by their families were

meticulously handed over, so much so that between “the ICRC and our

families we had better treats than our captors” (p. 170). When a fellow

prisoner, Hemapala, fell ill and died, the body was given a gun-salute

before being handed over to the International Committee of the Red Cross

(p. 153). It will be interesting to compare the treatment accorded to

Tiger cadres captured by the government, male and female – that is,

those who were not killed. One awaits testimony from that side.