A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Wednesday, October 17, 2018

The fate of the rupee: Time to stop playing the ‘blame-excuse-blame games’

Monday, 15 October 2018

As I have presented in a previous article titled ‘Rupee’s Sad Destiny of

One-way Journey to Depreciation’ (available at:

http://www.ft.lk/columns/Rupee-s-sad-destiny-of-one-way-journey-to-depreciation/4-654254),

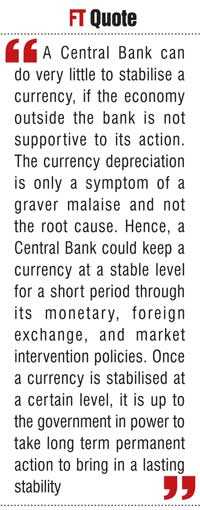

it has been a historical tragedy that the rupee has fallen in value

ever since the country had gained independence in 1948. At that time,

the rupee was exchanged for Rs 3.32 per US dollar. In terms of dollars, a

rupee was worth 30 US cents. This was more or less equal to the

exchange rate between the US dollar and the Singapore dollar that

amounted to 33 US cents. Under the fixed exchange rate system that had

been adopted by Sri Lanka till late 1977, this rate was devalued by the

government from time to time based in the devalued Sterling Pound rate

or the scarcity of foreign exchange reserves locally or both.

Accordingly, by 1977, the rupee/dollar rate had been devalued to Rs 8.41

per dollar or 12 US cents per rupee. When one adds the 65% Foreign

Exchange Entitlement Certificate or FEEC rate to the official exchange

rate, the rupee was effectively sold at Rs 13.88 per dollar or 7 US

cents per rupee. In November 1977, this rate was adjusted to Rs 15.56

per dollar or 6 US cents per rupee before Sri Lanka chose to go for a

flexible exchange rate system.

Since then, the rupee continued to fall in the market, eventually

reaching a level of Rs 172 per dollar in early October 2018. This was,

in dollar terms, equal to about a half of a US cent. Thus, the rupee

which was traded for 30 US cents in 1948 has now descended to the status

of a worthless currency. Figure 1 presents this one way journey of the

rupee, both in rupees to dollar and dollars to rupee terms, during

1950-October 2018.

Singapore’s problem is how to prevent appreciation of currency

The Singapore dollar, which started almost at the same level with Ceylon

rupee in 1948, has completed a journey in the opposite direction. Last

week, its value was recorded at 73 US cents per Singapore dollar, up

from 33 US cents in 1948.

But

unlike Sri Lanka, Singapore has been blessed with a continuing increase

in productivity, enabling it to allow the SGD to appreciate in the

market without losing its global competitive edge. However, its problem

has been how to prevent the SGD from appreciating beyond what is

permissible by improvements in productivity. Hence, to slow down the

appreciation and allow only a ‘modest and gradual’ rise, the country’s

Monetary Authority had in April 2018 slightly tightened the band within

which the currency is allowed to float in the market (see:

https://www.straitstimes.com/business/economy/mas-to-tighten-singdollar-policy-allowing-for-modest-and-gradual-appreciation

). Thus, the post-independence experience with respect to economic

performance and achievement of Singapore and Sri Lanka has been a way

apart from each other.

But

unlike Sri Lanka, Singapore has been blessed with a continuing increase

in productivity, enabling it to allow the SGD to appreciate in the

market without losing its global competitive edge. However, its problem

has been how to prevent the SGD from appreciating beyond what is

permissible by improvements in productivity. Hence, to slow down the

appreciation and allow only a ‘modest and gradual’ rise, the country’s

Monetary Authority had in April 2018 slightly tightened the band within

which the currency is allowed to float in the market (see:

https://www.straitstimes.com/business/economy/mas-to-tighten-singdollar-policy-allowing-for-modest-and-gradual-appreciation

). Thus, the post-independence experience with respect to economic

performance and achievement of Singapore and Sri Lanka has been a way

apart from each other.

Governments’ deficit spending is the root cause

All past governments in Sri Lanka, irrespective of their political

complexion, have to take responsibility for the country’s dismal

economic performance that has led to the depreciation of the rupee in

the market. Of course, Sri Lanka did not stay put where it started in

1948.

There have been achievements, but all of them had been small gains

compared to what other successful nations had attained. Sri Lanka’s

political leadership, like many other newly independent countries in

Asia, Africa and Latin America, had harboured obsessive faith in the

Government and Government financing for bringing quick prosperity to the

people. Hence, in the whole of the post-independence period, except in

1954 and 1955, the Government was in the wont of spending more than what

it earned – a budgetary practice known as deficit financing – by

tapping a combination of different funding sources. They constituted

borrowing from all sources – domestic private and banking sectors, on

one side, and foreigners, on the other – to fill the budget gap. Thus,

the country’s budget deficit in some years was as high as 19% of the

total output, known as the Gross Domestic Product or GDP, but on average

it stood at 7% of GDP, still an unmanageable level. But the average

real economic growth that was recorded during the whole of the

post-independence period amounted only to 4.4%, pretty much below the

required rate of 8% to make Sri Lanka a rich nation within a

generation.

According to the World Bank classifications, Sri Lanka was able to move

from a poor country to a lower middle income country only in 1997, some

50 years after the independence. It is still continuing as a lower

middle income country after 20 years, though it is now on the threshold

of moving to the next higher category, an upper middle income country.

All the evidence today shows that it has been snared in what is known as

‘the middle income trap’, a situation in which it is unable to become a

rich country soon, due to the absence of modern technology, and compete

with its peers due to increased labour costs back at home. What has

actually brought in is an undesired outcome. That is, Sri Lanka’s

economy has bloated in rupee terms beyond its ability to maintain

self-sustenance.

All Ministers of Finance in the past who have contributed to the

bloating of the economy through deficit financing are entitled to shout

only one desperate call. That is, ‘Honey, I Blew up the Kid’ like Wayne

Szalinski in Randal Kleiser’s movie, by the same title. Szalinski’s

work, leading to the creation of a monster out of an innocent kid in the

movie, was not intentional but accidental. Similarly, the creation of a

monster economy with a voracious appetite for filling a bloated belly

by Ministers of Finance was also not intentional but consequential.

Getting into a blame game

The ex-Governor of the Central Bank, Ajith Nivard Cabraal, in an article

titled ‘Govt, CB have abdicated the vital statutory duty by not being

able to deal with rupee depreciation (available at:

http://www.ft.lk/columns/Govt---CB-have-abdicated-vital-statutory-duty-by-not-being-able-to-deal-with-rupee-depreciation/4-664247)

had presented a statistical table with data from 1977 to the latest

with Central Bank intervention in the market to prevent depreciation of

the rupee.

Despite this, the rupee has depreciated from Rs 8.83 per dollar in late

1976 to Rs 171 per dollar at end September 2018. In fact, as I have

presented above, the rupee depreciation began much earlier, from the

date on which Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948. His point has been

that in the period from 2006 to 2014 during which he had been the

Governor, the rupee depreciated by about Rs 29 per dollar or 3% on

average a year with only sales from the Central Bank reserves amounting

only to $ 2.3 billion on a net basis. Though in 2011-2, CB had sold $ 4

billion to protect the rupee, the net sales during that period have been

reduced to $ 2.3 billion because of a mega net purchase of $ 2.3

billion in 2009, basically from the inflows to the government securities

market after that market was open to foreigners. His point was that

after he left the Bank in the period from 2015 to end September 2018,

the Bank has sold in the market on a net basis $ 2.5 billion but the

rupee had depreciated by Rs 40 per dollar or by 9% per annum on average.

This net sale is made up of a mega sale done by the Central Bank in the

period prior to the General Elections in August 2015, amounting to $

3.4 billion, and a further sale of $ 1.9 billion in 2016. But just like

Cabraal’s time, the present management of the Central Bank too has

purchased from the market on a net basis $ 1.7 billion in 2017,

augmenting the reserves.

Continuation of the blame game

Now,

this is playing a blame game that, during his time, both the

depreciation of the rupee and the net sale from the foreign exchange

reserves were lower than the period since he had left the Central Bank.

But still, the rupee depreciated and reserves were lost. However, the

Central Bank, in a defensive mood, had replied to Cabraal (available at:

http://www.ft.lk/opinion/Rupee-depreciation--Central-Bank-responds-on--misleading--article/14-664390),

pointing out that the Bank had in the past done its best to stabilise

the currency, given the constraints of unfavourable forces working

against both the rupee and Bank’s attempt at providing stability to the

exchange rate. Its main argument has been that in the current period, it

cannot and should not repeat the mega interventions done in the past,

namely, in 2011/12 and 2015, in view of the overwhelming debt repayment

obligations which have fallen on the country due to its liberal past

external borrowings. According to the Ministry of Finance, these

obligations are too critical to be ignored, especially in 2019 and 2020.

This has led to the continuation of the blame game, and Cabraal has in a

later intervention has questioned the Central Bank’s wisdom of

stabilising the rupee, whether it would fall to Rs 200 or Rs 250 or Rs

300 (available at:

http://www.ft.lk/columns/At-what-value-of-the-rupee-will-Central-Bank-think-it-needs-to-stop-the-depreciation--200--250--300-/4-664555).

These blame-excuse-blame games will not help the rupee or the economy

and, therefore, should be stopped in order to find a permanent solution

to rupee’s sad one way journey to depreciation, as I have argued in my

previous article.

Now,

this is playing a blame game that, during his time, both the

depreciation of the rupee and the net sale from the foreign exchange

reserves were lower than the period since he had left the Central Bank.

But still, the rupee depreciated and reserves were lost. However, the

Central Bank, in a defensive mood, had replied to Cabraal (available at:

http://www.ft.lk/opinion/Rupee-depreciation--Central-Bank-responds-on--misleading--article/14-664390),

pointing out that the Bank had in the past done its best to stabilise

the currency, given the constraints of unfavourable forces working

against both the rupee and Bank’s attempt at providing stability to the

exchange rate. Its main argument has been that in the current period, it

cannot and should not repeat the mega interventions done in the past,

namely, in 2011/12 and 2015, in view of the overwhelming debt repayment

obligations which have fallen on the country due to its liberal past

external borrowings. According to the Ministry of Finance, these

obligations are too critical to be ignored, especially in 2019 and 2020.

This has led to the continuation of the blame game, and Cabraal has in a

later intervention has questioned the Central Bank’s wisdom of

stabilising the rupee, whether it would fall to Rs 200 or Rs 250 or Rs

300 (available at:

http://www.ft.lk/columns/At-what-value-of-the-rupee-will-Central-Bank-think-it-needs-to-stop-the-depreciation--200--250--300-/4-664555).

These blame-excuse-blame games will not help the rupee or the economy

and, therefore, should be stopped in order to find a permanent solution

to rupee’s sad one way journey to depreciation, as I have argued in my

previous article.

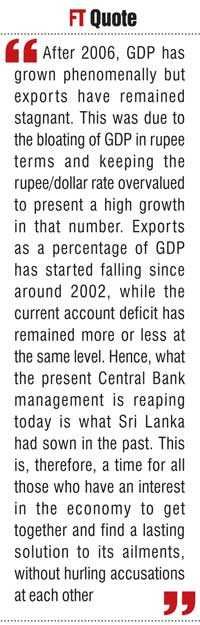

Permanent solution is the Government’s responsibility

A Central Bank can do very little to stabilise a currency, if the

economy outside the bank is not supportive to its action. The currency

depreciation is only a symptom of a graver malaise and not the root

cause. Hence, a Central Bank could keep a currency at a stable level for

a short period through its monetary, foreign exchange, and market

intervention policies. Once a currency is stabilised at a certain level,

it is up to the government in power to take long term permanent action

to bring in a lasting stability. This was exactly what Singapore did, by

increasing productivity through the introduction of new technology and

promoting competitiveness at all levels in the economy.

Financial war fought by the Central Bank

Every Central Bank Governor is working under this constraint, and can

only advise the political leadership what it should do. As the proverb

says, he can take the horse to the water but he cannot make it drink it.

In the severe foreign exchange crisis which the country faced during

2007 to 2009, when the country was at the height of the war with LTTE,

there was a separate financial war fought by the Central Bank along with

the war fought by soldiers in the battlefront. Sri Lanka lacked

weapons, and China, its main weapon supplier, extended only 3 months’

credit to the country. The Bank of Ceylon had to honour the letters of

credit on the due dates, and the Central Bank had to provide it with

dollars. The country had to save its foreign exchange to meet this

commitment on a priority basis, just like the present Governor, Indrajit

Coomaraswamy, has to save the scarce foreign reserves for meeting debt

repayment obligations.

Governor Cabraal’s creditable work

Cabraal should be given credit for managing that situation effectively,

thereby facilitating a continuous flow of weapons to the country for

soldiers in the field to move the war to a finish. I recall how he went

around the world in 2007, canvassing for investments by foreign

investors when the first sovereign bond issue of just $ 500 million was

offered by the Government. That was peanuts in today’s context, but it

was done against a very powerful force both within and outside the

country. But that was not sufficient and foreign exchange requirements

were alarmingly high. He dispatched himself to Libya to seek support

from Mohammed Gaddafi, supposed to be a friend of President Mahinda

Rajapaksa. But he returned empty-handed.

Then, he sent teams of senior Central Bank officers to major groups of

countries to solicit support of the Sri Lankan diaspora, who were

thought to be in readiness to give Sri Lanka much-needed dollars. I led

the team to Australia and New Zealand, met Sri Lankans living in

Melbourne, Sydney, Canberra and Wellington, and solicited support from

them. They were sympathetic but demanded the pound of flesh from the

Government in the form of a waiver of the fees charged for dual

citizenships, admission to superior schools, and duty free vehicles for

their relatives back at home. It was, thus, a failure.

Devoid of a source, Cabraal turned to IMF, which was sitting on the

request due to the pressure from those who were sympathetic to the LTTE.

The tables were turned only after the Indian Finance Minister, Pranab

Mukherjee came forward, and issued a bold statement that if IMF did not

approve of the loan sought by Sri Lanka, India would make available the

needed funds to that country in need. Hence, it is not cricket for

Cabraal to get into a blame game now, and find fault with the present

management of the Central Bank.

Unreasonable past Governors

Central Bank Governors in the past have been unreasonable at times, but

when sense was put to them, they came forward to support and protect

that institution.

In 1996, immediately after the horrendous bomb blast in front of the

Bank building, the late H N S Karunatilake began a blame game in public

that the then-Governor A S Jayawardena had failed to protect the bank

against a possible LTTE attack. In fact, he very correctly gave credit

to himself that the Bank was saved from total destruction by the iron

barrier he had constructed at the entrance, popularly nicknamed

Karunatilake Barrier. When the late A S Jayawardena came on TV and said

that at that instance of a national tragedy, all other Central Banks and

previous Governors had come to the Bank’s support, Karunatilake did not

mutter it again.

Then, after Cabraal became Governor in 2006, Karunatilake once again

went into the blame game, criticising him even personally. That was put

to a stop when Cabraal used his superior public relation skills to

invite all previous Governors to a luncheon meeting at the Bank, and

explained the true situation facing the country at that time.

High GDP and low exports are the cause of depreciation

Cabraal has another reason to support the present management of the

Central Bank. That is because the gravity of the rupee problem is rooted

to the period from 2006 to 2014, when Sri Lanka had bloated its economy

in rupee terms, and paid scanty attention to promoting exports or

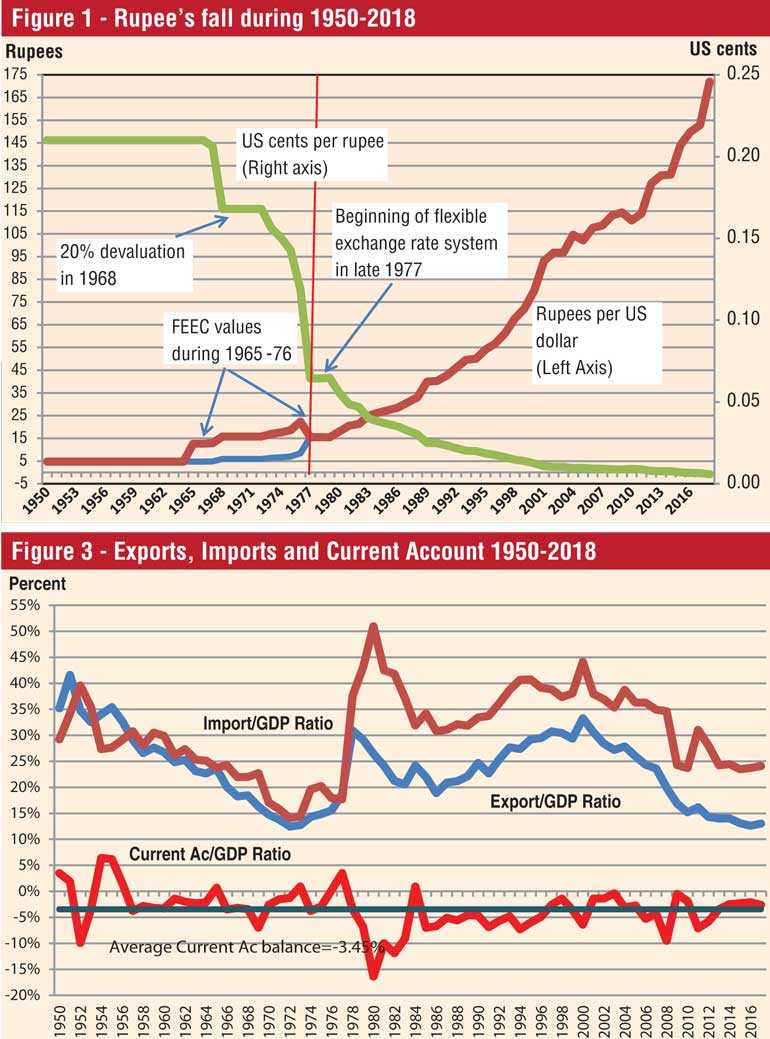

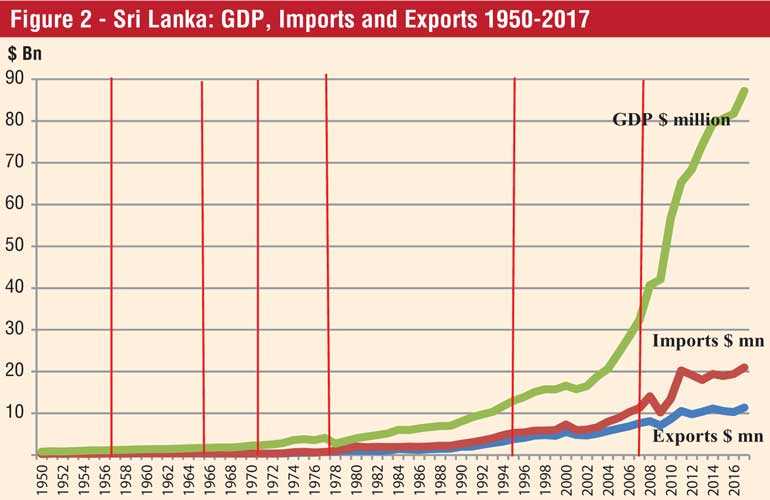

eliminating the deficit in the current account. As shown in Graph 2,

after 2006, GDP has grown phenomenally but exports have remained

stagnant.

This was due to the bloating of GDP in rupee terms and keeping the

rupee/dollar rate overvalued to present a high growth in that number.

This is shown by Graph 3, in which the exports as a percentage of GDP

has started falling since around 2002, while the current account deficit

has remained more or less at the same level.

Hence, what the present Central Bank management is reaping today is what

Sri Lanka had sown in the past. This is, therefore, a time for all

those who have an interest in the economy to get together and find a

lasting solution to its ailments, without hurling accusations at each

other.

Need is painful shrinking of spending by all

The solution involves getting the Government and the people to shrink

their top spending on a priority basis. No country can think of

stabilising its currency if it continues with a high deficit in the

current account unabatedly. Perhaps, it is better if all the parties in

the present blame game get together and shout, as in a previous

Szalinski movie, ‘Honey, I have shrunk the kids’. It is painful but

something that must necessarily be done.

(W A Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at waw1949@gmail.com)