A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Tuesday, August 31, 2021

Responding to skyrocketing food prices, Sri Lanka considers food rationing

29 August 2021

Responding to the skyrocketing food prices, Sri Lankan Trade Minister, Bandula Gunawardena, is set to propose a rationing system for sugar and essential items sold via Lanka Sathosa outlets, the largest retail chain in the country.

Over the past two weeks there has been a rapid increase in the price of goods such as sugar and dhal, with a kilo of sugar now costing Rs. 240 and a kilo of dhal now costing Rs. 245. Gunawardena attributes the rise in food costs to “fluctuating foreign exchange rates an increase of container handling and shipping charges and the shortage in supply compared to the demand”, reports the Sunday Times LK.

Despite this proposal the government has maintained that the private sector will to continue to work in its present form.

A further proposal being considered is to provide sugar, dhal and other essentials only for low-income groups at a controlled price.

Dependence on regional powers

Gunawardena has further reported an agreement with India to import 100,000 mt of rice varieties such as Nadu, Kekulu and Ponni Samba if there is an attempt by traders to increase prices. He also detailed efforts to decrease the price of Basmati by importing 6,000kg from Pakistan in three weeks.

Responding to the fuel crisis, Sri Lanka has turned to the United Aarab Emirates (UAE) to purchase crude oil and petroleum on a long-term credit basis. Energy Minister Udaya Gammanpila claimed that this could lead the government to save up to US$ 2 billion through this process where credit would be sought for six months.

SRI LANKA: UN Human Rights Mechanisms Ought to Explore New Approaches to Protect Rights

For several decades now, the widespread practice of enforced disappearances has been experienced in Sri Lanka in a very large scale

By Basil Fernando-August 30, 2021

Despite many attempts by the UN human rights agencies including the Working Group on Enforced Disappearances, there are hardly any cases where credible investigations or prosecutions have taken place concerning the cases which sometimes go into thousands which are being reported.

It is time for the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the UN Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Killings, and the Working Group on Enforced Disappearances to take steps to gain an understanding of this horrible practice. The approach to understand this widespread practice, should go beyond the legalistic approach of demanding investigations and prosecutions. One of the reasons for that approach is that the practice has shown that this approach has not produced any success.

If this extremely brutal form of punishment is to be brought under the scrutiny of the UN human rights mechanisms, it is necessary to understand the complex factors that have led to the adoption of this mode of punishment in Sri Lanka.

It will be surprising to find that in in Sri Lanka the death sentence on convicted criminals is usually not put into actual practice. This is quite a positive aspect.

However, the same country has no hesitation to cause enforced disappearances through its security agencies such as the Police, the military or paramilitary agencies. In most such cases, enforced disappearances mean abduction in place of arrest, torture and the extraction of information, the killing of persons in detention and also the disposal of bodies in secret. All these activities are carried out with direct or indirect approvals granted for the use of this form of punishment on some categories of persons.

In most cases, these persons who are thus subjected to enforced disappearances are pesons who for one reason or the other have come into conflict with the political establishment of the country. Sometimes, they are called terrorists. However, in enforced disappearances, the accuser, the investigator, the judge and the executioner are more or less the same persons. As the act of enforced disappearance is denied, there is no way to officially find out the reasons for these acts.

It has also been established that the actual persons who become the targets of such enforced disappearances are themselves not the real targets that are being pursued. The real target is the society in general. The need to create an ethos and an environment of fear in order to prevent any form of legitimate peaceful resistance against violations of rights and injustices is, the ultimate aim of these actions. Thus, the ultimate aims are of a political nature.

Before any real achievements could be made in order to stop these practices from the point of view of legal actions, it is much more important to gain insight into what has happened through studies into the political, social, psychological and other aspects that have provided the justification for such actions to be made possible. It requires much change in the political and moral ethos of a country before some officers working for the State could be motivated to undertake actions such as causing enforced disappearances.

If a serious attempt is made in corroboration with the experts in the fields of political science, sociology, psychology and other related branches of knowledge for in depth studies into these events, it would probably generate much more insight into these actions. Besides, it will also lead to the possibility of creating much more enlightened discussions and debates both in the relevant societies and also in the international arena. Such studies into these factors are very much missing.

Living at a time of great communication change as that is taking place at the present time, gaining greater knowledge about an issue could lead to the taking of many forms of action for the eradication of such an evil than merely relying on the legal mechanisms only.

Much more creative and innovative approaches are needed if the world is to gain a greater knowledge about what has made such large scale disappearances quite a part of the political tools of suppression in Sri Lanka, as well as elsewhere.

Many decades of the attempts to deal with such problems only by legal means only. have failed. It is necessary not to rely on the same means that have produced such negative results. By greater collaboration, the various branches of research may be able to create a discourse which could lead to positive steps being taken for the greater involvement of many stakeholders to resolve this terrible problem.

Relying only on legal means by demanding investigations and prosecutions had allowed Sri Lankan governments to adopt highly deceptive dealing with UN agencies. One of the latest attempts was the promise of investigations by the Missing Persons Office. Now, for all practical purposes, this office is itself missing. The room available for such deceptive reporting up and down has removed all seriousness out of government responses to UN demands.

A different approach is needed if justice relating to Enforced Disappearance is to become a reality.

The impact of disappearances on the body , Mind, Soul, and Society

EXTRAORDINARY ACTS OF CRUELTY can kill in physical terms, but they can also have a deadening effect on the cognitive faculties and emotional capacities in others. I have seen all that happening to individuals, groups, and entire societies.

I have known many innocent individuals who became victims of enforced disappearances, one of whom was illegally arrested by accident, and thereafter disappeared. This led to the gradual eating away of his brother’s body and mind, and eventual death. Medical doctors and psychologists could not explain his illness or cause of death. Similarly, another individual who had seen the pieces of his brother’s body, after he had been killed by rebels, also died after a slow decay, for which there was no rational explanation.

Anyone familiar with families of disappeared persons knows how often such tragedies happen, demonstrating a mind, body, and soul connection. At the same time, many others suffer various cognitive disorders from the awareness of such violence and cruelties. Deeper and deeper levels of confusion and demoralisation slowly erode cognitive functions.

The change that occurs is at the level of being itself; the layers of meanings embedded in each person’s consciousness when challenged in a fundamental way leaves a negative impact not only on individuals, but also on societies. When similar occurrences happen in societies, the negative impact enters into the human consciousness everywhere.

As a result, many types of deaths occur. Moral norms and associated beliefs that sustain life like a living stream, deaden, so that the living stream dries up. It finally reaches a point when such deaths themselves are celebrated as a triumph.

This death of moral norms occurs unconsciously, or subconsciously. Moral norms are the soil from which good intentions can rise; when the soil itself is not fertile, then the plants are affected. All kinds of deformed intentions begin to rise and spread. Nuclear bombs, projects that destroy natural resources and the climate are seen as right. Massive industries are created to do evil. This includes massive misinformation and fake news industries.

A world in which distinguishing good intentions from bad intentions is regarded as irrelevant stifles creativity and produces negativity. This negativity also gives rise to deep rebellions inside every person. The mind rebels against its destroyers; the psyche rebels against its tormentors; the soul rebels against its murderers.

Discoveries about human consciousness demonstrate not only interconnections between people, but also that our connection to the whole is the fundamental condition of our being. Parts of the body and society are being called upon to discover the unity between the parts and the whole. Suffering everywhere hastens our understanding of the unity of body, mind, soul, and society held together by an invisible thread.

The healing power of the all-embracing unity alone can cure the sick society we are living in at the moment.

It is possible to dissolve the deep conditions that have generated indifference and, at times, active and enthusiastic support for not just the murder of individuals but also large-scale massacres that amount to crimes against humanity. This indifference is so overwhelming that destruction of life from the earth itself is also considered as a matter of little importance.

Now, everything hangs on the awakening of the collective aspirations and will of humanity itself, which can only come forth from the depth of their beings. The intention to live and save can wipe out the forces of demoralisation, hopelessness, and negativity. It can bring back the vitality that will give rise to thousands of faces of creativity. The severance of body, mind, soul, and society can be replaced by the fundamental force of consciousness.

Looking for Raju

Amnesty International Poetry Competition, “Silenced Shadows,” 10 September 2015

What kind of a father are you, Asked his wife.

Where is he, our son,

Do you care at all…

How can I tell her what I know. Already so upset and depressed, How can she take any more,

What will become of her, he worried.

Events of the last few months, Like a film, rolled inside his brain; First it was, “Where is Raju,” Then, “Raju is missing.”

Then, more troubling news.

Raju was arrested;

Raju is in a detention centre; Which centre and how to find out.…

Then the journeys – one detention centre After another; strange places, Strange people, strange things.

Now, at sixty, he was entering into the unknown.

Head of a family, one that owed the obligation To explain, to console and to sustain hope,

To prevent a wife, a mother Going mad; fears of failure.

Where is Raju? No-one cares to answer. At every detention centre, the same reply, We know nothing about Raju,

Have not seen him or heard of him.

Where is the complaint,

The arrest warrant,

The interrogation record, the case file.

No answer to such questions.

Then, the powerful ministers Appear on television,

Denying any knowledge of Raju. Their hands are clean, they swear.

He is told many things by many people, Claiming that they saw the arrest

And the way he was dragged into a van.

Others speculated that Raju has been tortured.

But no-one explains why.

Perhaps, mistaken for a terrorist.

After all, he was a student, and many students are missing

He wonders, how to create a story To convince his wife that Raju is ok….

Raju has gone for a long journey, Raju will return soon.

At night, he dreamt his son was coming back, His son, embracing his mother.

And then, he sees his dead son,

Body found under a tree, with many injuries.

Days pass into months and then into years.

He is standing at the deathbed of an old woman, His wife, refusing to be reconciled,

Losing any speck of trust, muttering, Raju, Raju

They who stole his son, Have now killed his wife.

But, who are they,

Why do they do such things.…

“For truly great tragedies There are no explanations,” He wrote in his diary.

“But I must seek one.”

“This is about myself, who am I?”

A father who could not protect his child, A husband who could not console his wife,

An old man who cannot make sense of anything.…

I believed in civilisation, Human superiority over everything,

Of my link to the stars; What am I to believe now.…

I believed in rules and the law.

What is the rule, the law that allows stealing of the young,

And then making them disappear.…

I believed in the government’s accountability.

But, the president, the prime minister, Other ministers, refuse to see me And fail to answer my questions.…

Who is my neighbour after all.

Everyone avoids me Knowing I cannot be consoled.

They could say nothing of any value to me.

I will not cease to search,

I will not stop my questioning,

I will not die, but live to the end of time Seeking my son and asking questions from everyone.

When the State makes citizens disappear, A nation becomes another –

As a polluted river

Is no longer the same river.

To the task of washing the water clean,

To the painful process of a state admitting guilt, To the torturous path of people telling the truth To each other, my life is now committed.

***

Tens of thousands of such men, Such women, walk this country.

In the South, the North and the East, Everywhere, every day, asking the same questions.

On the same roads walk their tormentors Those who stole their children.

They may often meet and even exchange polite greetings,

not knowing who they are and how they are connected.

4,562 persons test positive for COVID-19; over 5,000 delayed cases added to total

- Total patient count rises to 436,081, includes 323,090 from New Year cluster

- 162,101 patients detected from Western Province during third wave

- 55,098 persons under medical or home-based care

- COVID-19 recoveries rise to 371,992

By Shailendree Wickrama Adittiya-Tuesday, 31 August 2021

Sri Lanka’s COVID-19 detections rose to 436,081 with 4,562 COVID-19 new cases yesterday and the addition of over 5,000 delayed cases to the country’s total.

The Epidemiology Unit states that a total of 5,350 COVID-19 cases detected between 24 and 27 August were yesterday added to the total COVID-19 patient count after verification.

Meanwhile, more data discrepancies were yesterday pointed out with Trincomalee Regional Director of Health Services Dr. B.G.M Costa saying close to 9,000 COVID-19 patients have been detected from Trincomalee District thus far.

“In August alone, 4,000 COVID-19 patients were detected, and 232 COVID-19 deaths have been reported during the third wave,” Dr. Costa said.

However, the Epidemiology Unit’s situation report published yesterday shows a total of 3,700 COVID-19 detections from Trincomalee and only 3,045 detections during the third wave.

Health officials state that the patients detected yesterday were from the New Year cluster. According to the Health Promotion Bureau, 13,696 PCR tests were carried out yesterday.

On Sunday, 13,446 PCR tests and 4,384 rapid antigen tests were carried out and 4,612 COVID-19 positive persons were detected. This includes 4,608 persons from the New Year cluster and four persons from the Prisons cluster.

The total patient count of the New Year cluster is 323,090 and the patient count of the Prisons cluster is 8,158.

In addition to this, the country’s local cases also include 82,785 persons from the Peliyagoda cluster and 3,059 persons from the Divulapitiya cluster.

The country’s imported cases consist of 6,835 Sri Lankans and 328 foreigners. According to the Epidemiology Unit, 97,663 patients from Colombo, 78,708 patients from Gampaha, 43,619 patients from Kalutara, 23,825 patients from Galle, and 20,830 patients from Kurunegala have tested positive for COVID-19 to date.

Third wave detections include 65,366 persons from Colombo, 60,174 persons from Gampaha, 36,561 persons from Kalutara, 21,176 persons from Galle, and 17,609 persons from Kurunegala.

Meanwhile, 10 parliamentarians tested positive for COVID-19 in August, the latest to contract the virus being Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) Kurunegala District MP Asanka Navarathne. He posted on Facebook yesterday that he had tested positive for COVID-19 and requested all persons he came into contact with in the last few days to self-quarantine.

Despite a quarantine curfew in place until 6 September, crowds can be seen on the street, with no severe restrictions enforced on travel. When questioned about this, Health Promotion Bureau Director Dr. Ranjith Batuwanthudawa agreed, saying: “If this continues, it will become difficult to control the disease.”

At present, 55,098 persons are under medical or home-based care, with 3,307 persons suspected of having COVID-19 under observation.

According to the Epidemiology Unit, 2,182 persons left hospitals yesterday, raising the country’s COVID-19 recoveries to 371,992.

UN report to HRC 48: Human rights situation in Sri Lanka has deteriorated to a point that will threaten transitional justice process

Image: The Special Rapporteur regrets the insufficient progress made regarding truth-seeking in Sri Lanka.

By Sri Lanka Brief-

In the follow-up on the visit to Sri Lanka Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence, Fabián Salvioli says that “over the past 18 months, the human rights situation in Sri Lanka has seen a marked deterioration that is not conducive to advancing the country’s transitional justice process and may in fact threaten it. The Special Rapporteur deeply regrets the insufficient implementation of the recommendations made by his predecessor and the blatant regression in the areas of accountability, memorialization and guarantees of non-recurrence and the insufficient progress made regarding truth-seeking.”

This report will be presented to the upcoming 48 session of the UNHRC for a interactive dialogue.

Sri Lanka Section of the report fellows:

IV. Follow-up on the visit to Sri Lanka

24. The former Special Rapporteur visited Sri Lanka from 10 to 23 October 2017 at the invitation of the Government. He presented his end-of-mission statement with preliminary findings and recommendations on the visit in November 2017 and presented his final report to the Human Rights Council in September 2020.16 The present report contains an assessment of the status of implementation of the recommendations made in the country visit report, which had already been formulated in the end-of-mission statement of October 2017.17 This is to ensure sufficient time has been allowed for their implementation.

25. The Special Rapporteur regrets that no submission for the present report was received from the Government of Sri Lanka. Comments to the present report were received on 9 July 2021.

26. The commitments made by the administration led by President Maithripala Sirisena to undertake constitutional reforms, strengthen oversight bodies, curb corruption and engage with the international community to provide accountability for past abuses, including through implementation of Human Rights Council resolution 30/1, took an abrupt turn with the presidential elections in November 2019. The new administration, led by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, proceeded to withdraw Sri Lanka from its international commitments regarding transitional justice, including in respect of resolution 30/1. This political shift has translated into a slowdown in the transitional justice agenda and a reversal of some of the progress made during the previous administration.18

27. Concerning accountability for past human rights violations, the Special Rapporteur regrets the lack of substantive progress in the investigation of emblematic cases, despite initial progress. Under the previous administration, the Criminal Investigation Department had made progress in investigating some violations, enabling some indictments and arrests; the High Court Trial-at-Bar held a hearing in the case of disappeared journalist Prageeth Eknaligoda; a High Court at Bar was appointed for the Weliveriya case; the Attorney General reopened investigations into the 2006 killing of Tamil students in Trincomalee; and indictments were served against suspects in the murder of 27 inmates at the Welikada Prison and against suspects in the 2013 Rathupaswela killings.

28. However, progress on several emblematic cases has stalled or encountered serious setbacks under the current administration. Investigations into military and security officers allegedly linked to serious human rights violations have in several instances been suspended. In some cases, the alleged perpetrators have been promoted despite the allegations against them. The commission of inquiry to investigate allegations of political victimization of public servants established by the current President has intervened in favour of military intelligence officers in ongoing judicial proceedings, including in the 2008 murder of journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge and the 2010 enforced disappearance of Prageeth Eknaligoda. It has also issued directives to the Attorney General to halt the prosecution of former Navy Commander Admiral Wasantha Karannagoda and former Navy Spokesman Commodore D.K.P. Dassanayake in relation to the killing of 11 youths by Navy officers, which have been rejected by the Attorney General.19 The Court of Appeal also issued an interim injunction order staying the case, following a writ submitted by Mr. Karannagoda. The case is due to be heard by that Court. The above-mentioned commission of inquiry has also interfered in other criminal trials, including by withholding documentary evidence, threatening prosecutors with legal action and running parallel and contradictory examinations of individuals already appearing before trial courts. In April 2021, the Prime Minister tabled a resolution seeking legislative approval to implement the recommendations of the commission of inquiry to institute criminal proceedings against investigators, lawyers, witnesses and others involved in some emblematic cases and to dismiss several cases currently pending in court. A special Presidential commission of inquiry composed of three sitting judges is to decide on the commission’s recommendations.

29. Efforts to ensure accountability have been further obstructed by reported reprisals against several members of the Criminal Investigation Department involved in the past in investigations into a number of high-profile killings, enforced disappearances and corruption.20 Some have been arrested and later released on bail, and another has left the country.

30. The current administration has shown that it is unwilling or unable to make progress in the effective investigation, prosecution and sanctioning of serious violations of human rights and humanitarian law, which deeply worries the Special Rapporteur. In this context, he welcomes the adoption in March 2021 of Human Rights Council resolution 46/1, by which the Council decided to strengthen the capacity of OHCHR to collect and preserve evidence for future accountability processes for gross violations of human rights or serious violations of international humanitarian law in Sri Lanka and present recommendations to the international community on how justice and accountability can be delivered. The adoption of the resolution was opposed by the delegation of Sri Lanka, which cited ongoing domestic remedies and independent processes.

31. The Special Rapporteur regrets that no truth commission has been established to date. Such a mechanism would be of considerable value in helping Sri Lanka to understand the root causes of the conflict and open a common public platform for all communities to share their lived experience.

32. During the period 2015–2019, progress was reported in the work of the Office on Missing Persons, which opened four regional offices in Batticaloa, Jaffna, Matara and Mannar covering also adjoining districts, adopted a psychosocial support strategy for families of disappeared persons in consultation with victims and other stakeholders and participated in forensics and archiving training. However, since 2020 progress has stalled and the Office has faced interference from the Government, which reportedly intends to review the law establishing and defining the mandate of the Office and which has appointed the former Chair of the commission of inquiry to investigate allegations of political victimization, Upali Abeyrathne, to head the Office. As the original set of commissioners ended their mandate in February 2021, there is considerable concern that this and other new proposed appointments will seriously undermine the independence and credibility of the institution, eroding victims’ trust in it and weakening the Office’s ability to discharge its mandate effectively.21 The Government has reported that the commissioners have been appointed following constitutional procedures.

33. The Special Rapporteur urges the Government to maintain its support for the Office on Missing Persons, including by providing it with sufficient resources and technical means, and to guarantee its independence and effective functioning.

34. The Special Rapporteur is concerned about the several instances since November 2019 in which government authorities have tried, through judicial action, to suppress memorialization efforts by families of victims and conflict-affected communities, citing security as well as COVID-19-related public health risks.22

35. The harassment, threats, surveillance and obstruction of activities of victims and human rights defenders has reportedly increased both in frequency and intensity in 2020, which the Government justifies as related to security concerns. In one reported case of reprisal, representatives of families of the disappeared in the North-East who attended Human Rights Council sessions in 2018 and 2019 were subjected to surveillance, harassment and intimidation upon their return to Sri Lanka. Families of the disappeared and witnesses to human rights violations have reportedly been harassed in similar ways.23

36. In July 2019, the Office on Missing Persons issued a protection strategy and established a dedicated unit for victim and witness protection that has developed procedures for the documentation of protection concerns and has reportedly intervened in relation to attacks against family members and other stakeholders involved in court proceedings in disappearances cases. The Government must ensure that victims, witnesses and human rights defenders are able to carry out their invaluable work in safety and without fear of reprisal. The Special Rapporteur reiterates his call for victims, witnesses and human rights defenders to be better protected as a key component of the transitional justice process in Sri Lanka.

37. With respect to guarantees of non-recurrence, on 22 October 2020 Parliament adopted the twentieth amendment to the Constitution introducing fundamental changes in the relationships and balance of power between the different branches of government. The amendment, which the Government argues was adopted following constitutional procedures, has strengthened the power of the President and the executive, effectively reversing many of the democratic gains introduced by the nineteenth amendment, adopted in 2015. It has also significantly weakened the independence of several key institutions, including the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka and the National Police Commission (whose Chairs can now be appointed and dismissed by the President), as well as the judiciary (senior judges and members of the Judicial Service Commission are now appointed by the President).24 The Government contends that institutional independence remains unchallenged despite the changes introduced by the new amendment.

38. There has also been a deepening and accelerating militarization of civilian government functions. On 29 December 2019, the Government brought 31 public entities under the oversight of the Ministry of Defence, including the police, the Secretariat for NonGovernmental Organizations, the National Media Centre and the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission. It also appointed 25 senior army officers as chief coordinating officers for maintaining COVID-19 protocols in all districts. In July 2021, the Government reported that most of the public entities that had been under the oversight of the Ministry of Defence were no longer under its purview.

39. Several special procedure mandate holders25 have strongly recommended replacing the Prevention of Terrorism Act with legislation that complies with international standards. While the previous Government had initiated alternative legislation that raised concerns from a human rights perspective26 and was later shelved, the present administration has failed to make any progress in this regard. Instead, in March 2021 the President issued a set of regulations on deradicalization and countering violent extremist religious ideology under the Prevention of Terrorism Act that allows for the arbitrary administrative detention of people for up to two years without trial. Several arbitrary arrests under the Prevention of Terrorism Act have been reported in the past year, many involving Tamils and Muslims. Furthermore, over 300 Tamil and Muslim individuals and organizations have been labelled as terrorist and included in an extraordinary issue of the official gazette. The Government has reported that it has commenced a process of reviewing some provisions of the Act and has accordingly released detainees held in extended judicial custody. The Special Rapporteur urges the Government to place an immediate moratorium on arrests under the Prevention of Terrorism Act, with a view to repealing it as a matter of priority, and undertakes prompt, effective and transparent legal review of all persons detained under the Act.

40. Sri Lanka is yet to set up a land commission to document and carry out a systematic mapping of military-occupied private and public land for effective and comprehensive restitution. The Government has reported that 89.26 per cent of State land and 92.22 per cent of private land occupied by the military has been released and that the rest will be reviewed, taking into consideration strategic military requirements. A scheme will reportedly offer compensation to holders of private land unreleased owing to national security concerns. The Special Rapporteur recalls that the mapping and restitution of land must be entrusted to an independent and impartial body.

41. Over the past 18 months, the human rights situation in Sri Lanka has seen a marked deterioration that is not conducive to advancing the country’s transitional justice process and may in fact threaten it. The Special Rapporteur deeply regrets the insufficient implementation of the recommendations made by his predecessor and the blatant regression in the areas of accountability, memorialization and guarantees of non-recurrence and the insufficient progress made regarding truth-seeking. He urges the Government to swiftly revert this trend in order to comply with its international obligations.

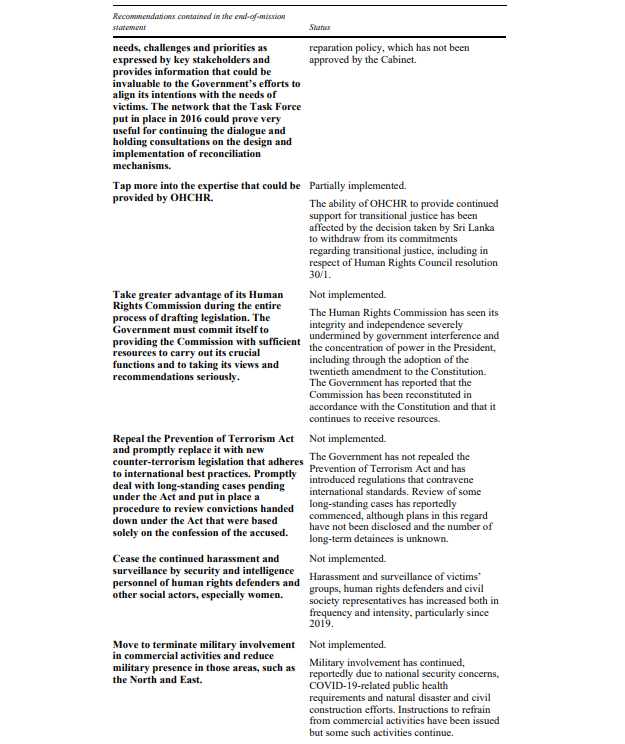

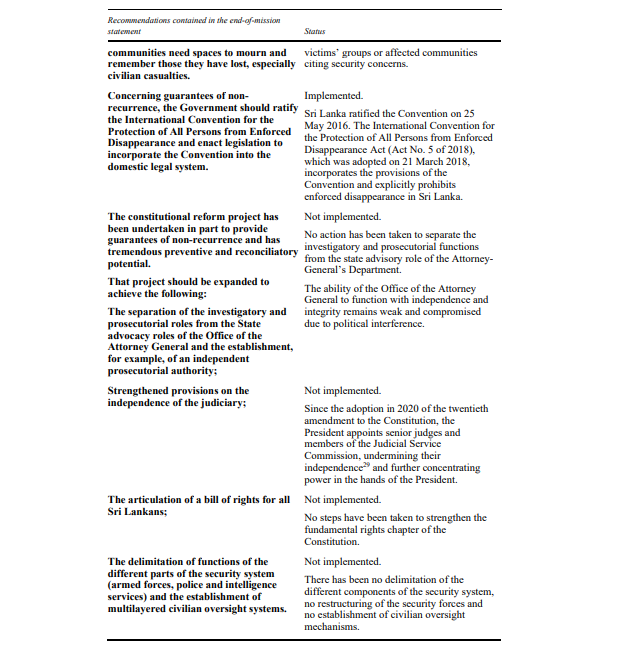

Sri Lanka: status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the visit

report, which had already been formulated in the end-of-mission statement of October 2017

V. Concluding remarks

42. The Special Rapporteur expresses concern about the insufficient progress in the implementation of the recommendations addressed to the reviewed States. He urges the States to accelerate implementation and recalls that many of the recommendations represent the development of treaty obligations assumed by States that require compliance.

( OHCHR)

Namal Rajapaksa claims Tamil refugees are welcome despite systemic torture

29 August 2021

Responding to the announcement of welfare benefits for Eelam Tamil refugees by Tamil Nadu’s chief minister M.K. Stalin, Sri Lankan minister Namal Rajapaksa claimed that the Rajapaksa administration welcomed back Tamil refugees whilst omitting ongoing accounts of torture.

Those who have returned and who require assistance have been provided with houses & livelihoods. Pres @GotabayaR & PM @PresRajapaksa will ensure all refugees who return back are safe in their homeland & can restart their lives. 2/2

— Namal Rajapaksa (@RajapaksaNamal) August 28, 2021

Earlier this year, the British Upper Tribunal ruled recognised the threat of torture Tamil asylum seekers faced upon return to Sri Lanka. The court further that e "authoritarian and paranoid" Sri Lankan government monitors the activities of the Tamils diaspora and “drew no material distinction between the violent means of the LTTE and non-violent political advocacy”.

Read more here: How a landmark British ruling may save Tamil activists from deportation to Sri Lanka

![]()

According to the International Truth and Justice Project, there have been 178 documented credible cases of torture from 2015-2018, excluding 22 individuals abroad who reported torture following the UN special investigation. Since Gotabaya Rajapaksa came to power in late 2019, at least 5 cases have been documented abroad of abduction, torture and sexual violence of Tamils. The ITJP notes, "this likely represents the tip of the iceberg".

The ITJP details that:

In one case, the independent medico-legal report corroborates recent torture and rape and maps 59 cigarette burns on the victim’s body including her upper thighs and genital area. The victim attempted suicide three times in Sri Lanka and now in the UK has to be locked in her room at night to prevent her from accessing kitchen knives or tablets to try again.

Refugee camps

பல கட்ட போராட்டங்களை முன்னெடுத்து பலனிக்காத நிலையில் திருச்சி சிறப்பு முகாமிலிருக்கும் 15க்கும் மேற்பட்ட இலங்கை தமிழர்கள் அளவுக்கு அதிகமான தூக்க மாத்திரைகளை சாப்பிட்டும், வயிற்றைக் கிழித்துக்கொண்டும் தற்கொலை முயற்சி (thread) pic.twitter.com/QR9huJMADA

— Sonia Arunkumar (@rajakumaari) August 18, 2021

Stalin’s announcement follows weeks of protest by Eelam Tamil refugees who have demanded to be released from designated camps. Earlier this month several refugees attempted suicide in a special camp in Trichy Central Jail following the rejection of their demand for the release.

Some of the detainees consumed large amounts of sleeping pills while others slit themselves in the stomach in an attempt to commit suicide.

Stalin’s programme designates 3.17 billion Indian rupees (£3.1 million) to improve the welfare of these refugees and includes renovating existing settlements, increasing the provisions of essential goods, and offering scholarships for students pursuing a degree in engineering and other skill development programmes.

Whilst a welcome development, there remains in India over 90,000 Eelam Tamil refugees. India’s Ministry of State for Home Affairs reports that there are 58,843 Eelam Tamil refugees incarcerated in 108 state-run camps across Tamil Nadu. A further 34,135 Eelam Tamil refugees are staying as “non-camp” refugees in Tamil Nadu where they are required to report to the police on a regular basis and 54 Eelam Tamil refugees are staying in a refugee camp at Malkangiri, Odisha.

Eelam Tamils have been denied citizenship under the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) which was passed in 2019 with the support of all 11 All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) members in the Rajya Sabha. Recently the central government told the Madras High Court that, “We can’t provide citizenship for Sri Lankan refugees who entered India illegally and don’t possess any documents,” and that the centre cannot make decisions on an “emotional basis.”

Commenting on conditions in the camps, K.Manikkavasagam (name changed on request), an inmate of Madapam camp near Rameswaram, Told HuffPost India:

“In the camps, we live in the shadow of fear and insecurity. We are not allowed to move around in town. There are restrictions on talking to the media. All our basic rights have been curtailed. Three or four decades in a camp means you are incapable of doing anything worthwhile in life. We are always discriminated.”

Related Articles:

Confronting the State on Disappearances

Photo courtesy of Mirak Raheem

MIRAK RAHEEM-

August 30 is marked across much of the world as the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances. For the families and the friends of the disappeared and human rights groups working on the issue in countries such as Sri Lanka, which have experienced large scale disappearances, it provides an opportunity to remind those respective societies and governments of their responsibilities to address the crime and its victims. While seeking state and public acknowledgement, it also provides a space for reflection, on how far (and how slowly) we have moved on issues of justice, truth, reparations, and to build resolve on pushing onward.

This year’s commemoration comes a month after the passing away of Manouri Muttetuwegama, who played a prominent role in the struggle for disappearances for at least three decades, both as a part of civil society and as a member of independent state mechanisms. A renowned Attorney-at-Law, Manouri served in key positions, including as chair of the All-Island Commission on Disappearances, commissioner of the Human Rights Commission and chairperson of the Consultation Task Force for Reconciliation Mechanisms, helping advance the cause of justice and human rights. To me she was a senior activist, wise counsel, fellow comrade in the struggle for human rights and a friend. In this piece, I want to focus on something that she shaped and invested herself in, and that also marked a milestone in the struggle for disappearances – the Final Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Involuntary Removal or Disappearance of Persons in the Western, Southern and Sabaragamuwa Provinces (Final Report). The lines of reasoning, the framing of issues and the turn of phrase speak of Manouri’s commitment, determination and above all empathy to this issue. Although 24 years has passed, the Final Report remains so relevant.

Milestone in the struggle for disappearances

For a country that is addicted to commissions, a Commission of Inquiry (COI) as a milestone may seem a misplaced notion. Sri Lanka has had over a dozen temporary, ad hoc mechanisms with mandates to look at the issue of disappearances (either exclusively focused on the issue or as part of wider human rights). These COIs and special committees were broadly meant to examine the problem and provide recommendations, but too often served as smoke screens. Sets of personalities of some standing were appointed to carry out inquiries and serve as proof that the state was doing something. The reports or recommendations in such cases were not always made public or acted upon in any comprehensive manner. When the appointed individuals were persons of integrity and determined to fulfil their duty to the public, however these reports could prove potent. Such a report could provide a mirror to confront the state, force a conversation on tough issues, and to precipitate a process of acknowledgement.

Assessing the impact of such commissions can be difficult because it is not merely evaluating the process and the report for its comprehensiveness, credibility, accuracy and effectiveness, but how it is received in a political environment and acted upon. In examining the impact of the Final Report, it has to be looked at alongside its two other sister commissions, together referred to as the Zonal Commissions, and the All Island Commission that immediately followed. In terms of the history of the struggle on disappearances, these four commissions, stand out as a moment when the State was forced to acknowledge the crime of disappearances and provide some redress, particularly on reparations, including the provision of compensation and death certificates for the victims. The search for the disappeared and the prosecution of perpetrators, however, was largely restricted to a handful of high-profile cases. The political will to bring about more systemic reforms and to investigate and prosecute such cases rapidly waned and Sri Lanka faced yet another cycle of disappearances in the context of the civil war. Families of the disappeared will judge these COIs harshly as they expected them to provide answers to the fate of their loved ones, and are not satisfied by recommendations, as opposed to actions.

Confronting the State

The recommendations of the Final Report provided a critical starting point for laying out the responsibilities and obligations of the State to respond to the disappearance question. At a time when transitional justice was at a nascent stage with South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission in session, the Report provided a basic framework for Sri Lanka to think through issues of justice, reparations and non-recurrence. It highlighted the importance of counselling and community approaches among its relief measures, some of which the Government instituted, such as a compensation programme. It listed out a series of preventive measures, including ending the practice of unauthorized places of detention and reforming the Emergency Regulations, which if instituted could have limited the space for the continuation of enforced disappearances in the next decades. These recommendations would be reiterated by local civil society actors and by the UN Working Group on Enforced Disappearances, and also the Office on Missing Persons. While the recommendations are ambitious, they were also rooted in ground realities. For instance, the Report recommends the establishment of a Human Identification Centre to assist in dealing with mass graves, while cautioning the State against excavating until the required expertise is built up.

The Final Report confronted the State with irrefutable evidence that Sri Lanka had experienced mass disappearances. While courts establish legal facts, COIs can provide political facts based on law. Previous COIs appointed during the tenure of Presidents R. Premadasa and D.B. Wijetunga, which were supposed to look at the issue of disappearances proved unable to overcome challenges such as limitations in mandate, lack of will and the political context. It was with the COIs established under President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga that the debate transformed, with the State being forced to confront itself. The responsibility for bringing about this moment has to lie with the families of the disappeared and the organisations working on this issue, especially the Mother’s Front with opposition politicians.

The foundation for the Final Report lay in the solid process followed by the COI to assess facts of the disappearance. For a start, the sittings provided an official forum for victims to be heard, which was especially significant given the context of denial, hostility and violence faced by those who had attempted to speak out. After calling for complaints and reaching out to a broad range of actors (sending out up to 16,800 complaint forms) 8,739 cases. The COI held inquiries through sittings in the three provinces into a majority of cases (7,761), following which the COI sifted out those who fell outside the mandate (including outside the time bar, or who had gone missing due to personal disputes), based on witness statements and official documentation. A total of 7,238 cases of involuntary disappearances were established by the COI and were listed out in Volume 2. This list not only conveys the sheer scale of the problem and acknowledges the individuals who were disappeared, but continues to be relevant in the efforts to build a centralized list of all the disappeared in Sri Lanka.

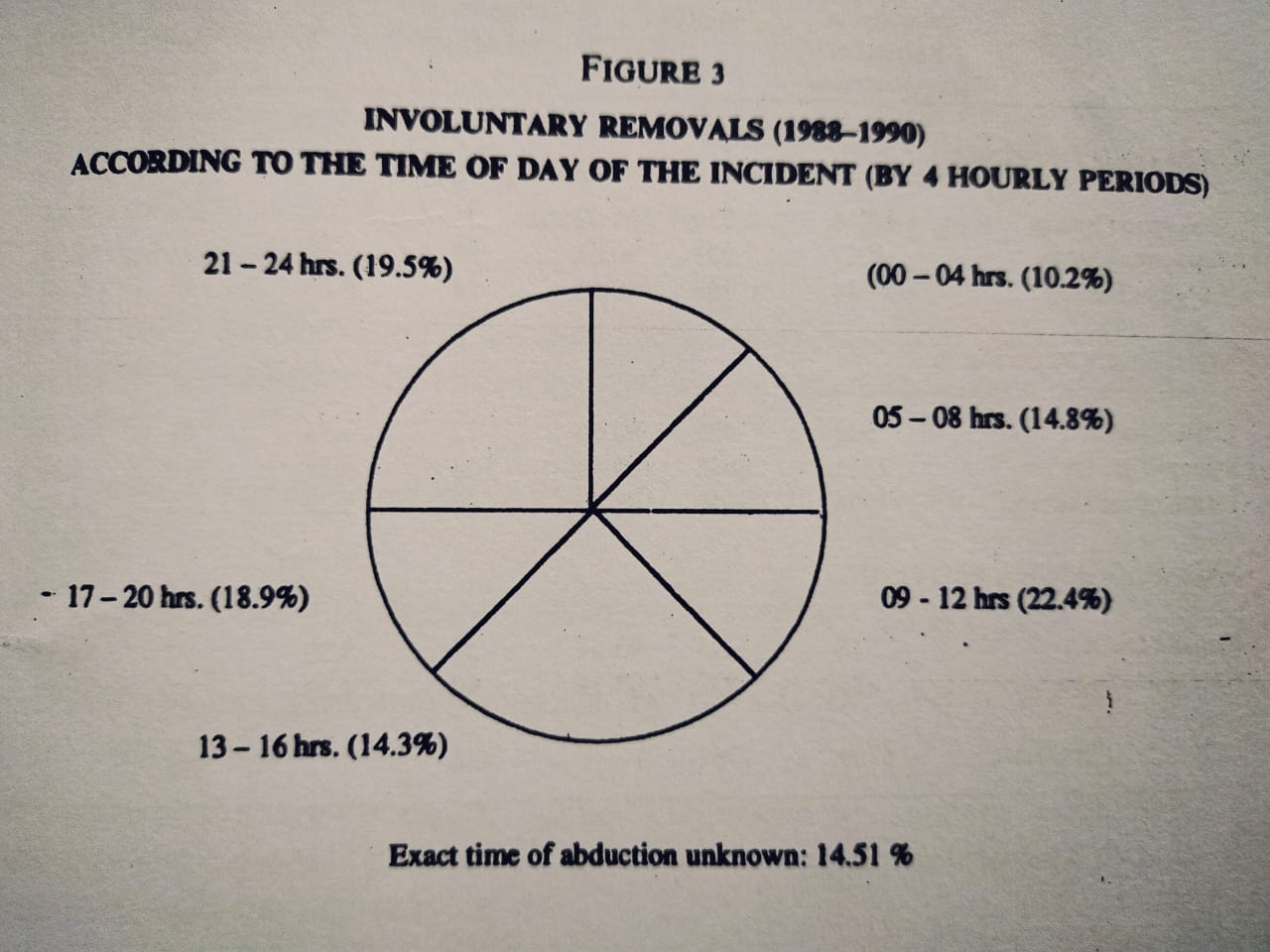

The Final Report established an official narrative of the disappearances and makes for grim reading: 68 or 0.77% were children below the age of 15; 1.12% were 98 Buddhist priests; Matara District contributed to the largest number of disappearances (27.13%) of the eight districts; the busiest time of day for disappearances was 9 am to 12 pm. Often borrowing phrases from victims and of the time, the narrative effectively conveyed the terror and helplessness that they experienced: “During the sittings of this commission, we repeatedly heard the saying, “when we went to the police station, we were chased away like dogs’” (p.XV). In talking about the overall scenario in the South as the State forces fought the JVP the position of civilians was described as “giriyata aju vechcha puwak gediya wage” (p.160) – like the arecanut caught in the nut cutter. Symbolically the Report speaks of ‘disappearances,’ as opposed to using the more ambiguous term of ‘missing,’ which acknowledged intentionality and was in keeping with development in international human rights law.

In order to make its case the Final Report provided the details of a series of individual cases to prove its assertion, simultaneously capturing some of the countless tragedies that unfolded across the country. On the threats faced by lawyers and petitioners who filed cases on disappearances, it lists out the testimonies of different families who had family members or their lawyer subjected to threats, intimidation, or even killed or disappeared. In one instance, the father had filed a Habeas Corpus Application for his son who was abducted and went to court to give evidence, but he too disappeared, forcing the surviving family members to withdraw the case for fear of their lives (p.107).

Faced with a State machinery that not only rejected its involvement in carrying out disappearances but that the disappearances even took place, the Final Report, through the testimonies and its investigations, was able to repudiate the denials. “A feature that struck us most forcefully in our inquiries was the utmost care that had been taken not only by individual perpetrators but also by the system itself to prevent those occurrences from being reflected in the official records of the country” (p.XV). For instance, state officials sought to refute the existence of secret and unofficial detention centres, such as the Sevana Army Camp where the disappeared Embilipitiya School Boys were believed to have been kept. The COI was able to locate the food register providing valuable evidence to prove the presence of detainees (p.56). The Final Report built a strong case to prove the systemic nature of disappearances and culpability of the State, using 9,744 witness testimonies, including that of abductees who were released and senior military and police personnel (pp.34-5). For instance, the Report highlighted the practice of persons surrendering to the Government Agent, who in turn would hand them over to rehabilitation camps, but that some of these surrendees disappeared in the system (p.27).

The Report dedicated a chapter to the culture of impunity that enabled disappearances, listing out key features – “the sight of scavenging dogs feeding on mutilated bodies left in piles on the road side”; tyre pyres and necklaces of burning tyres, the complaints of disappearances that if accepted would omit critical details; and “the knowledge, worst of all, shared by the whole community, that there would be no official acknowledgement, not noe [sic] perpetrator punished, even though these were not the acts of a foreign invader” (p.51).

The Report pursued a critical line on accountability, highlighting the culpability of State agents. Of the 7,239 cases of proven disappearance, 4,858 were carried out in collaboration with the state and para military groups working in collaboration, while 59 cases were by personal enemies acting in collaboration with agents of the state; only 1,543 were by perpetrators unknown (p.29). The Report went on to highlight the failure to prosecute despite a “clear chain of evidence” (p.54). Following its mandate to unearth “any credible material indicative of the person or persons responsible” for disappearances and in response it submitted a list of names of persons confidentially to the President where there was prima facie evidence (p.67). The Report also confronts the JVP with its culpability in 779 disappearances (p.29), stating that it was not simply an effort to overthrow the state but also stifle any opposition to it (p.44), punishing not just individuals but his/her family in a brutal manner (p.45-6). The Final Report thus provides an official account of a dark and tragic moment in this country’s history.

From denial to duty?

In successive decades, other COIs were established, including the Lessons Learned and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) and the Paranagama Commission, which examined the issue of disappearances and made recommendations in this regard. While they fell short of the benchmarks set by the Final Report, nonetheless they provided official documentation of disappearances, including those that took place during the last years of the war. It would be more than two and half decades after the Final Report that there would another major milestone with the establishment of the Office on Missing Persons in 2018 – a permanent and independent state mechanism with the primary responsibility of conducting the search for the many thousands of disappeared and missing. This signalled the state’s recognition of its obligations to the disappeared. This is part of a necessary shift from disappearances being an issue that is addressed at the whim of political regimes to a permanent state responsibility. The passage of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances Act in the same year marked a symbolic moment in explicitly recognizing the crime of disappearances. In pushing through both reforms, which came on the back of the UN Human Rights Council Resolution 30/1, the late Mangala Samaraweera played a significant role and was an ally in furthering the cause of disappearances over the decades, including with the Mother’s Front.

Looking at where the issue of disappearance stands today, it appears that there has been a significant advancement in law and institutionalization, yet the space and the will to carry out truth seeking, and the search and to pursue justice seem remote. In a context where denial of disappearances has regained political currency, the reports from many of these commissions, including the LLRC and Paranagama, can play an important role to thwart the shifting of goal posts to false debates and tropes, by once more reminding the State and political society that disappearances are part of the official narrative and that the State has duties and obligations to the citizens of this country, especially the victims who have been disappeared.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)