A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Monday, March 30, 2015

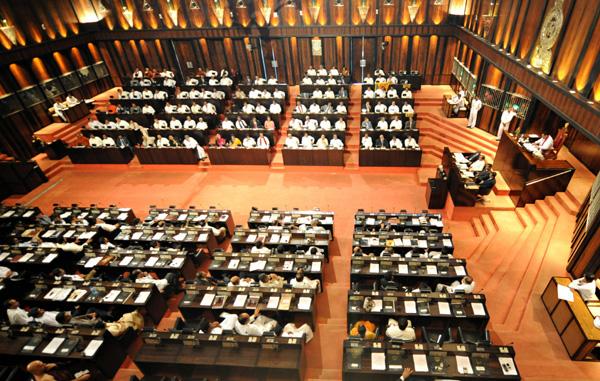

From 225 To 250; This Is Too Dangerous A Joke

By Kusal Perera -March 30, 2015

“New look at electoral reforms: 250 seats” – Sunday Times lead story on 29 March, 2015

Sri Lankan political leaders from the South live with a political

perversion in creating this region’s largest projects. This greedy trend

is now talked of asMahinda Rajapaksa’s

giant derailment in creating white elephants. Within them, the less

popular giants include a 235 acre MR National Tele Cinema Park in

Ranimithenna at a cost of over Rs.200 million, a hitherto incomplete

Hambantota Sports Zone with indoor and outdoor facilities, including a

18 hole golf link, all planned for the 2018 CW Games at a total cost yet

to be estimated, the Sooriyaweva international cricket stadium at a

cost of Rs, 700 million that since 2011 had seen only 05 international

cricket matches. But Mattala international airport, Magampura port,

Colombo Port City, Lotus Tower are the popular visits for all political

opponents of MR.

Can

these abuses be reduced to individual greed? Nay, they are also about

centralised power in Colombo and Sinhala politics. Centralising power in

the hands of Sinhala leaders has been the core ideology of Southern

politics in post independent Ceylon and now Sri Lanka. Therefore even

before an Executive Presidency took total control, there were South

Asia’s largest condensed milk factory built in Polonnaruwa to produce

“Perakum” condensed milk and an international cricket stadium in

Dambulla, now almost closed up. These don’t come merely as greedy ego

trips, but are made possible with political power centralised in

Colombo. Such would not be possible if provincial power had been

effectively devolved, leaving the Colombo power centre to deal with only

national policy, defence and external affairs. That as often happens

and given no attention, we are now coming to head with another massive

proposal for electoral reforms. Reform for an increase in the number of

MPs from 225 to 250.

Can

these abuses be reduced to individual greed? Nay, they are also about

centralised power in Colombo and Sinhala politics. Centralising power in

the hands of Sinhala leaders has been the core ideology of Southern

politics in post independent Ceylon and now Sri Lanka. Therefore even

before an Executive Presidency took total control, there were South

Asia’s largest condensed milk factory built in Polonnaruwa to produce

“Perakum” condensed milk and an international cricket stadium in

Dambulla, now almost closed up. These don’t come merely as greedy ego

trips, but are made possible with political power centralised in

Colombo. Such would not be possible if provincial power had been

effectively devolved, leaving the Colombo power centre to deal with only

national policy, defence and external affairs. That as often happens

and given no attention, we are now coming to head with another massive

proposal for electoral reforms. Reform for an increase in the number of

MPs from 225 to 250.

Electoral reforms are necessary. The present system with preference

votes for individuals within a proportionate count for political parties

has deformed the representative democratic structures of governance at

every level. Then CJ Sarath N Silva’s ruling on crossovers has further

defamed and derailed the whole representative character in an elected

parliament. All of them have to be put to right.

The trillion Yuan question therefore in present day Sri Lanka should be,

“What do we expect from electoral reforms?” Is it to accommodate tiny

political parties in parliament that just scrape through with 05% plus

votes ? Is it only to allow major political parties to form stable

governments in Colombo ? Is it to allow compromises and consensus

amongst political parties in gaining better numbers in parliament? Why

do we actually need electoral reforms for ? A simple answer would be,

reforms are needed to clear all existing deformities in all elected

bodies to strengthen people’s representation in democratic governance.

This brings us to the question, “Can people’s representative democracy

in Sri Lanka be strengthened, with electoral reforms restricted to a

single large parliament?” I have a firm “NO” to that. Yet the whole

discussion on electoral reforms is only about the parliament. A few

weeks ago, I was a passive participant in a discussion forum organised

by a few NGO experts on electoral reforms. While the organisers provided

good calculations on past elections juxtaposed on different formulas

for a mixed bag of elected representation between the First Past the

Post (FPP) and Proportional Representation (PR), the whole discussion

centred on how best to achieve consensus within the present parliament.

It was all about numbers and how the next parliamentary elections could

be held as promised in the 100 Day programme. It seemed, for all who

were there, political power is about the number of MPs who’d gather in

the Diyawanna Wild Life Sanctuary and nowhere else. Here lies the catch

and here lies the tragedy in getting back to a saner democratic

governance structure through reforms.

No electoral reform in Sri Lanka can brush aside the fact that we have

in front of us, the most depressingly prolonged national conflict since

independence. A conflict that went through unwanted and unnecessary

blood baths and one that still yearns for a decent, workable political

solution based on power sharing with Colombo. We cannot therefore ignore

the fact that we live with constitutionally devolved power to the

provinces and also smaller representative entities in local governance.

Our governance structure therefore is three tiered. It cannot be

tinkered heavily at the top.

Parliamentary electoral reforms thus have to be talked of in terms of a

parliament that will have to take note of the fact that its powers have

been devolved to the provinces. An issue we keep ignoring for the sake

of the South. Before the Indo-SL Accord in

1987, our parliament was elected by the people to govern every aspect

of their socio economic, cultural and political life, in every hamlet

anywhere. Therefore every school, every hospital in the island, was the

subject of the Colombo parliament. Provincial economic planning and

rural development was held with the Colombo government. Provincial

housing, roads and bridges in provinces had to be planned, financed,

constructed and maintained from Colombo. So were social services and

rehabilitation, animal husbandry, irrigation, agriculture and agrarian

services, public commuting within provinces, co-operatives and more.

They were all devolved to provincial councils with the adoption of the 13th Amendment.

Even with all such responsibility, 225 elected MPs for a population of

20 million were in excess, compared to other countries with similar

democratic governing structures.

The problem with this XXL representation begins with the 13th Amendment

becoming law. When Provincial Councils (PC) were to be established under

the 13th Amendment, we should have asked ourselves the question, “What

are we going to do with a parliament of 225 MPs hereafter ? Once half

the responsibility is devolved to new PCs ?” That was never asked and

answers found. We continued as usual. We do not need such a hefty

parliament any more to handle much less responsibility. With the

adoption of the 13th Amendment, we should have brought down the

parliament to the size it was, at least in 1970. That would have meant a

parliament of 151 MPs, much less cabinet and deputy ministers and a

massive saving on tax payers’ money.

Into a new political culture since 1978 that bred growing corruption and

power hunger in a free market economy, the parliament took no time to

ponder on pruning itself to suit new and less responsibility. Society

was shot into silent survival with the JVP gunning down any who

supported devolution and PCs. Therefore political leaders and MPs had

the advantage of a numbed society that could not discuss and debate the

entirety of the 13th Amendment, its impact and the new formations of

governing structures. We thus continue to live with an electoral system

that accommodates a tadpole type representative democracy. With an

oversized parliament swallowing billions of tax payers’ money spent in

maintaining it, we say the PCs a waste of public funds.

If we compare ourselves to India where responsibility of governance of

provincial life is handed over to State Governments, Haryana State is

one that tells us, we are horribly oversized. Haryana State has close to

23 million, just 02 million people more than us, the whole of Sri

Lanka. Haryana State consists of 15 districts and the 23 million people

elect only 90 members to their State Assembly. They believe, 90 State

Assembly members are adequate to take charge of all provincial

responsibilities including socio economic development. Therefore, these

23 million people of Haryana elect just 10 MPs to the parliament, to the

Lok Sabha. With local responsibilities taken care of at the State

government level, they need only 10 MPs to represent them at national

policy making, national security and on other national issues.

Compare this with our PCs and the parliament. Colombo district with only

2.3 million people elect 40 members to the Western PC and 19 to

parliament, when Haryana with 23 million elects only 90 members to State

Assembly and 10 to Lok Sabha. We are projecting large where we don’t

have to. Obviously it’s the “Asia’s largest miracle” mentality. When 23

million people in Haryana are represented in parliament by 10 elected

MPs, we have a parliament of 225 MPs. with Colombo experts, policy

makers and political party leaders discussing reforms to further

increase numbers.

Electoral reforms are necessary for the people. Electoral reforms should

answer people’s issues and needs. The way the reforms are being schemed

and manipulated at present, wholly out of reach of the people, reforms

are to serve political parties and their leaders at parliamentary level.

Mind you, political parties in Sri Lanka are as corrupt as any State

and nongovernmental institution. They are no democratic organisations

either. Their increased numbers in parliament ignoring the fact that we

are already into devolution at provincial level and the fact we are hard

pressed to find answers to the Tamil political conflict that can only

be on the basis of a workable power sharing governing model, we are into

further chaos. Therefore what is being discussed as election reforms

can be too dangerous and too expensive to live with if they find passage

through parliament.