A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Monday, August 29, 2016

Defeating Labour’s manufactured anti-Semitism crisis

Asa Winstanley-26 August 2016

In June, Chakrabarti published the report of her inquiry into anti-Semitism and other forms of racism in the party.

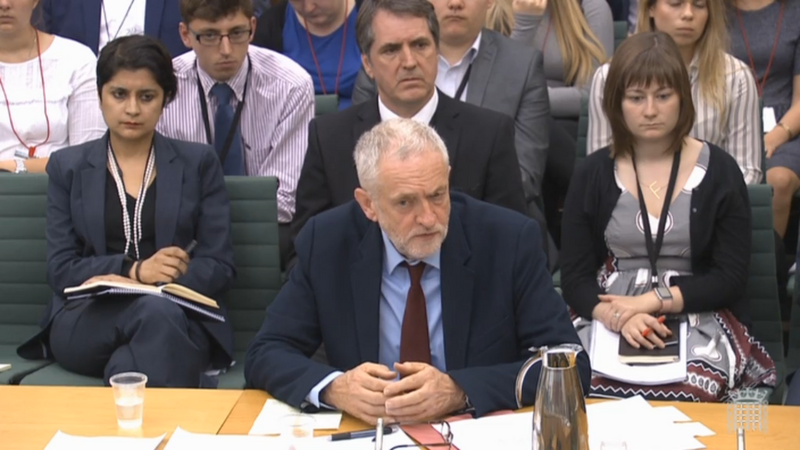

The inquiry was set up by party leader Jeremy Corbyn two

months earlier, as a way of dealing with allegations of anti-Semitism

that had dogged the party since Corbyn was elected as leader in

September 2015.

But as The Electronic Intifada’s reporting exposed at the time, the “anti-Semitism crisis” was a media fabrication.

Although there were a few cases of anti-Semitic statements by Labour

members made on social media – often years before Corbyn was even

elected leader – the vast majority of the evidence was exaggerated or

simply fabricated.

One of the main aims of this campaign of defamation was to damage Corbyn in the run-up to May’s local elections.

Chakrabarti approached the inquiry with a deep, and personal,

understanding of the reality of racism. Part of the UK’s Asian

community, her family has experienced racist violence.

She also added something that had been missing from the start of the manufactured crisis: an evaluation of the evidence.

Her report concluded that “the Labour Party is not overrun by

anti-Semitism” but that there is a “minority” of “hateful or ignorant

attitudes.” She recommended new procedural rules, rather than sweeping

changes to the party rule book.

Twenty allegations

After all was said and done, how many actual concrete allegations of anti-Semitism were made?

According to testimony provided by Corbyn during

his appearance before a parliamentary committee last month, “in total,

less than 20 [members] were suspended, all of which was part of a due

process.”

Twenty allegations of anti-Semitism. Certainly a problem, but hardly a “crisis” in a party with half a million members.

And yet, the press coverage was stark: the pro-Israel Jewish Chronicle ran a front page story in March claiming that “Labour now seems to be a party that attracts anti-Semites like flies to a cesspit.”

The liberal Guardian’s leading columnist Jonathan Freedland claimed in March that the UK’s Jewish community was “fast reaching the glum conclusion that Labour has become a cold house for Jews.”

The most significant of Chakrarbarti’s proposed rule changes was “the

insertion of a legally qualified panel into the disciplinary process”

and removal of the power of interim suspensions from party staff who act

under the orders of the party’s general secretary.

Derailing

The media attending the launch of the report, overwhelmingly hostile to Corbyn as always, attempted to derail the event. Some journalists falsely reported that a Jewish MP was abused in anti-Semitic terms, and Corbyn had compared Israel to Islamic State.

In fact Ruth Smeeth, a Labour MP and former Israel lobbyist,

had simply been accused by one campaigner of “working hand in hand”

with the right-wing media. Smeeth had taken part in June’s attempted coup against Corbyn by resigning a minor position in the shadow cabinet.

The Guardian misquoted Corbyn as saying “our Jewish friends are

no more responsible for the actions of Israel or the Netanyahu

government than our Islamic friends are responsible for Islamic State.”

He had actually said that Jews were no more responsible for Israel’s

actions “than our Muslim friends are for those of various self-styled

Islamic states or organizations.” The paper later issued a correction

after pressure on social media.

Despite all this, the Chakrabarti report largely succeeded in its aim of

defusing the anti-Semitism “crisis” and beginning the process of

healing wounds within the party.

“The Labour Party has always been a broad coalition for the good of

society,” she wrote, “we must set the gold standard for disagreeing

well.”

However, current attempts to portray the report as a “whitewash for peerages” scandal jeopardize these efforts.

A peerage is an appointment that gives a person the right to sit in the

UK Parliament’s unelected upper chamber, the House of Lords.

Change of tune

The report was widely welcomed by groups who had submitted evidence to the inquiry. Such groups includedthe Palestine Solidarity Campaign and even some groups critical of Corbyn due to his record of support for Palestinian human rights.

Jackie Walker, vice chair of the pro-Corbyn Labour group Momentum, welcomed the report’s “well

thought through and sensible recommendations” but regretted that the

inquiry had failed to attract “a significant number of submissions” from

Black and other ethnic minority groups.

Walker was suspended for several weeks in May before being reinstated after being cleared of “anti-Semitism.”

The Jewish Labour Movement responded to the report saying it was a “sensible and firm platform.” The group, whose chair Jeremy Newmark is deeply involved in anti-Palestinian campaigning, has been criticized by some Jewish members of Labour for systematically excluding them and refusing to represent their critical views on Israel.

The Board of Deputies of British Jews, a pro-Israel organization, welcomed “aspects”

of the report and said it appreciated “the careful way in which Shami

Chakrabarti has engaged with our community and that she took on board

and addressed some of our concerns with commendable speed.”

But, more than a month later, with the news about Chakrabarti’s nomination to the House of Lords, the Boardchanged its tune, and accused Labour of a “whitewash for peerages” scandal.

Chakrabarti was the only person nominated by Labour to the Lords. Corbyn has said as prime minister he would abolish the unelected body and replace it with an elected chamber.

After news of the Chakrabarti peerage came out, Channel 4 News journalist Michael Crick claimed that Corbyn had broken a “pledge” not to nominate new peers to the Lords.

However, Channel 4’s own footage indicates

that Corbyn had not made a clear pledge on this issue while campaigning

for the Labour leadership last year. Although Corbyn stated he could

“see no case” for nominating new peers, he did not explicitly rule out

making such nominations.

Report’s implications

Since the so-called “crisis” has died down for now, it is a good time to

take a look back on the Chakrabarti report and reflect on some of its

lessons. The document is nuanced and thoughtful. Above all, a clear

attempt has been made to engage with the evidence.

What it does not do is address the details of every single allegation of anti-Semitism in the Labour Party.

Instead it proposes a clear way forward, by taking the power of interim

suspension out of the hands of the National Executive Committee (NEC),

and instead moving it to the National Constitutional Committee, or NCC,

the party’s disciplinary body.

This may sound like a rather mundane change. But it is significant for two reasons.

Firstly, the NEC in practice rarely carried out interim suspensions. As

Chakrabarti notes, these were in fact usually carried out by party staff

acting under the leadership of the general secretary.

This is currently Iain McNicol, who has come in for intense criticism for what Corbyn’s backers say is an attempt force the leader out and to rig the current leadership election against him.

Chakrabarti writes that “testimony to my inquiry reveals the sheer

inadequacy of the in-house resources in an organization understandably

primarily equipped for political campaigning rather than due process.”

This leads into the second reason for the importance of this change:

Chakrabarti says that the NCC will from now on have to consult with a

new legal panel before making interim suspensions. The members of the

the panel will be lawyers appointed “for a fixed term of five years.”

Defeat for the witch hunt

In most ways, this is a defeat for the witch hunters who have been using

false and exaggerated claims about anti-Semitism to purge the party of

pro-Corbyn and Palestine solidarity members.

As reported by The Electronic Intifada,

the main culprit for these mostly politicized suspensions was McNicol’s

Compliance Unit, also known as the Constitutional Unit.

Chakrabarti’s report does not single out the unit, but it seems clear

she includes it when she refers to a “sheer inadequacy of the in-house

resources” and to the need for legal expertise.

She also writes of the importance that suspended members from now on be

“clearly informed of the allegation(s) made against them, their factual

basis and the identity of the complainant – unless there are good

reasons not to do so.”

Suspended members were often not told the reasons why

or the nature of the allegations. Chakrabarti writes that some members

“found out about their suspensions and investigations as a result of

media reporting rather than notice from the party itself.”

“Completely unfair”

This fits in with The Electronic Intifada’s reporting. Victims of the witch hunt were often targeted by anti-Palestinian groups and right-wing media who put the Labour Party under pressure to suspend them.

McNicol’s Compliance Unit would then immediately suspend the accused,

usually based on fabricated or decontextualized evidence. The unit would

then report or leak the suspension back to the hostile journalist who

had approached them for comment.

And so another headline about an “anti-Semitism crisis” would be

generated. In some cases, there is reason to believe the leaks to

right-wing media may have been the initiative of McNicol’s party staff.

Chakrabarti writes that this was “completely unfair, unacceptable and a

breach of data protection law that anyone should have found out about

being the subject to an investigation or their suspension by way of the

media and indeed that leaks, briefing or other publicity should so often

have accompanied a suspension pending investigation.”

From now on, any member suspended should be immediately informed and

“any press inquiries followed up with a standard line that all

complaints are followed up expeditiously.”

Chakrabarti’s also wrote that care should now be taken to “create an

important distinction” between genuine complainants “and a hostile

journalist or a political rival conducting a trawling exercise or

fishing expedition.”

Macpherson confusion

In another important defeat for anti-Palestinian groups, Chakrabarti

rubbished attempts to misuse an influential racism definition to

misrepresent Palestine solidarity as anti-Semitism.

She wrote of a level of “confusion (in some quarters) about the

‘Macpherson’ definition of a racist incident.” This is a reference to

the report of a 1999 inquiry into how the London Metropolitan Police

mishandled the investigation into the murder of Stephen Lawrence, a Black teenager.

Lawrence had in 1993 been murdered by a gang of white racists who were

never brought to justice – mainly because police did not take the case

seriously. William Macpherson, a retired high court judge, found in his report that London’s police force was affected by “institutional racism.”

Supporters of Israel have in recent years tried to piggyback onto

Macpherson’s widely respected report by claiming that their enemies’

groups are “institutionally anti-Semitic.”

In 2013, an employment tribunal dismissed the

Israel lobby’s costly legal action against the University and College

Union for “institutional anti-Semitism” as “devoid of any merit” and “an

impermissible attempt to achieve a political end by litigious means.”

Janet Royall, who conducted an inquiry into the now-debunked claims of rampant anti-Semitism at Oxford University Labour Club bizarrely wrote in May of her “disappointment and frustration” that she had found “no institutional anti-Semitism” at the university.

False narrative

While attacking the left, the fashionable claim of anti-Palestinian

propagandists in recent years has been essentially that, if a Jewish

person says something is anti-Semitism, therefore that thing is by definition anti-Semitism.

Chakrabarti in her report explains why such an approach is both seriously flawed and based on a “confusion” about Macpherson.

This confusion was best summed up elsewhere by the inquiry’s co-chair,

Professor David Feldman, of the Pears Institute for the study of

anti-Semitism, as highlighted by the excellent Free Speech on Israel blog.

“It is sometimes suggested,” he wrote in a report to the House of

Commons, “that when Jews perceive an utterance or action to be

anti-Semitic that this is how it should be described.”

Feldman explained that “Macpherson intended to propose that such racist

incidents require investigation. He did not mean to imply that such

incidents are necessarily racist. However, Macpherson’s report has been

misinterpreted and misapplied in precisely this way.”

Transition

Chakrabarti writes that Macpherson means an incident reported “should be

recorded as ‘racist’ when perceived that way by the victim” but that

this should “in no way determine” the outcome of the investigation.

“Investigation and due process must of course then follow,” she writes,

which may ultimately conclude there was no attack, or that such an

attack had a motive other than racism. The same principle should apply

in Labour, she concluded.

Corbyn has endorsed Chakrabarti’s recommendations, and there will now be

a period of transition while they are implemented. Meanwhile, although

the manufactured “crisis” has died down, it seems likely that the media

and the right wing of the Labour Party will continue to attempt to revive it as a stick to beat Corbyn with.

It fits into a wider false narrative about how the party under Corbyn has supposedly become an “abusive” hive of “Troyskyist” and “lunatic” activity.