A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Thursday, November 3, 2016

Pushpe’s Lanka

Art by Koralegadara Pushpakumara. Barbed Wire (xiii) 2012 Screen Print, Acylic on Canvas 110×67.5 cm.

Excavation (school uniform, burnt tyre) 2004 Mixed media 210 x 54 cm.

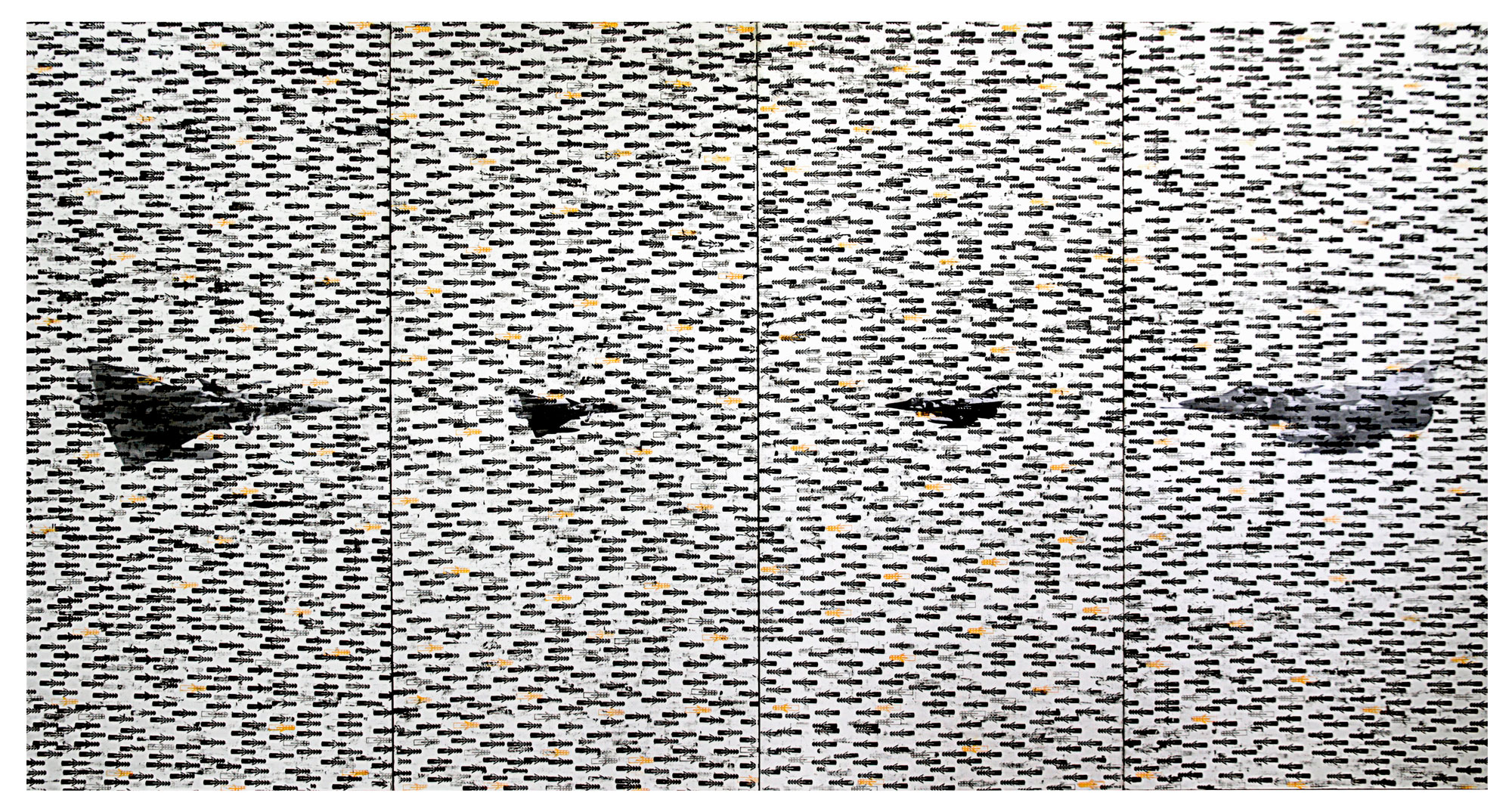

Wall Plug (16) 2013. Mixed media on canvas 190.5 x 360 cm.-Barbed Wire (xii) 2012 Screen Print, Acylic on Canvas 110×67.5 cm.

Excavation (school uniform, burnt tyre) 2004 Mixed media 210 x 54 cm.

He

can see through the threatening spikes of barbed wire. He is anguished

recalling the nightmarish experiences of violent outbreaks. But he was

hardly hopeless eyewitness. He allows his works to narrate such

experiences, and while doing so he adds aesthetic idioms to experiences

of past. Koralegadara Pushpakumara takes us on imaginary flights mixing

romance and reality. His truth claims in the artworks result into an art

of sarcasm. As fondly called by friends, Pushpe has endeavored to

conjure an image of Sri Lanka neatly blending his personal experiences

and public history. This is not the Lanka that tourist guidebooks

describe; nor do state officials discuss about it. Pushpe’s Lanka has

come to India in a show of his select works, titled Dissonant Images ongoing

at the gallery Exhibit 320 in New Delhi. Like some of his compatriots,

Pushpe’s Lanka invites art-lovers to reconfigure Sri Lanka. This is an

aesthetic imagination of Lanka at the cusp of romance and reality.

Suffice to say, it underpins the experiences of the artist who was an

active eyewitness of insurgency, political violence, and civil war in

Sri Lanka. The curious combination of symbols in his works present

experiential accounts loaded with sarcasm.

I Saw Them Die and Disappear: Eyewitness Artist

Koralegadara Pushpakumara hails from a family of carpenters with

ambitious artistic inclinations toward woodwork. The famous woodcarvings

of the Gadaladeniya and Ambekka temples in Kandy were the source of

inspiration for the growing Pushpe. He aspired to continue with his

calling and experiment with woodcarving, but could not stay away from

the political revolution, which was in the offing. As a growing child,

he had encountered caste discrimination that his friends from the lower

caste groups had experienced. With a sense of Buddhist equality at the

top of his mind, he was dismayed about the divide between Govigama(the

land-owning upper caste group among Sinhalas) and Rodi (a lower caste

group, which technically exists outside of the Sinhala caste system and

were traditionally confined to jobs of low esteem).Like many Sinhala

youth, he inched towards the transformative dream of the political left

and it’s most concerted manifestation popularly known as JVP (Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna or people’s liberation front).

Most of the youths inclined to the JVP attended their political

indoctrination lectures in desolate locations around Peradeniya and

Kandy.

Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna was formed in 1960s including

initially as a Beijing-leaning Marxist outfit. It has a history of a

twofold critical periods. One was the armed struggle against the ruling

government in 1971, and the other was the more violent uprising during

1987-1989.Making an appeal to the masses justifying the struggle, the

JVP’s leader of the time, Rohana Wijeweera asserted,

“When the government violates the rights of the people, insurrection is

for them the most sacred of rights, the imperative of duties. The only

remedy against authorized force is to oppose it by force” (Quoted by R.

Gunaratna in Sri Lanka: A Lost Revolution, published by Institution of

Fundamental Studies, 1990, p. 120).

The 1971 uprising against the Bandaranaike government attracted

attention worldwide. The crackdown of the uprising claimed the lives of

more than ten thousand youths in Sri Lanka. Wijeweera was arrested and

imprisoned in Jaffna, among other places. This bitter defeat led to the

vengeful JVP latter insurgency that lasted from1987-1989. In this spell,

armed JVP cadres attacked the Sri Lankan government, state machineries,

as well as the people who opposed the violent strategies of the JVP and

many ordinary people who were simply in the wrong place at the wrong

time. Moreover, certain units of the JVP aggressively fought against the

Indian Peace Keeping Force occupying northern and eastern Sri Lanka at

time and in general successfully mobilized an anti-India sentiment

preventing Lankan folks from consuming Indian goods. However, the result

of this uprising too included massive casualty of the innocent people,

JVP cadres, government personnel, and the life of the JVP leader,

Wijeweera too.

It was in this situation of an exceedingly decimated JVP that as an

active cadre Pushpkumara experienced a threat to his own life, and fled

to Ampara, located in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka. He recalls that

he used to have a cyanide pill in a locket hanging from his neck those

days, so as he could commit suicide if he was arrested. But he could not

escape arrest. In his own words, “in 1989, I was a final year student

at school, a 21 year old activist of the student movement attached to

the JVP that rose against the Sri Lankan government. Then the government

crack down on the JVP began. Being an active JVPer, in fear of

persecution, I fled to Ampara, where another war against the Tamils was

going on. In this border village, I was captured, detained and tortured.

Finally, miraculously, I was released for which the exact reason is

still not fully clear to me.”

He was a fugitive still performing his artistic woodwork at his

brother’s workshop in Ampara and was sought after among local

householders who thought his works provided a good and affordable

decorative frills for their living rooms. He had by this time realized

the consequences of the uprising, violent loss of lives rather than the

promised structural transformation. He witnessed the elaborate mechanism

of killing employed by both the JVP and the Sri Lankan armed forces and

police. He watched in helplessness the notorious necklace, the circle

of burning tyres to asphyxiate and simply burn rebels and suspects.

Pushpe recalls, “many thousands disappeared and were killed both in the

war and in the uprising”. He adds further, “After 15 years, being an

ex-JVPer and an active artist, I joined an institute in Colombo to do a

post graduate diploma in archeology. The assignment was about dating

dead bodies. I couldn’t escape the flashback. And my question was could

anyone find and date dead bodies of contemporary youth who had

disappeared, and the people who were massacred in the war in North. They

will be under burnt tires with engine oil mixed decaying, charred

clothes. You wouldn’t find the typical succession of insects, other

creatures and decaying patterns – you would need a different theory to

explain and date them”.

Inevitableness of Politics in Sri Lanka

He returned to Colombo and obtained a formal art education from the

Institute of Aesthetic Studies, University of Kelaniya in 1997.Pushpe

became one of the early artists in the contemporary visual art in Sri

Lanka that has been discussed as “1990s trend” by the eminent art

historian and doyen artist Jagath Weerasinghe.

Along with Jagath, Anoli Perera and others contributed to this trend,

creating a new paradigm of artistic practices under the institution

named Theertha Artists’ Collective based in Colombo. A vivid turn to the

political underpinned the visual arts at Theertha. And the political

undercurrents and appeals of these artworks subsumed the individual

self, socio-cultural traditions, and politico-public encounters of

violence. Thus, in Jagath’s analysis, “Pushpe is quite conscious of the

sociocultural underpinnings that forms the basis of his existence as a

painter”. This is very evident in some of the most famous works of

Pushpe that have been featured in various exhibitions including the one

ongoing at the gallery, Exhibit 320 in New Delhi. Pushpe articulates his

motif and objectives, saying, “the patterns and motives in my work

connects and resonates patterns and motives seen in traditional Sri

Lankan art. My attempt is to build an idea about the establishing

post-war cultural patterns”.

For example, his series titled ‘Goodwill Hardware’ and ‘Barbed Wire’

stand testimonial to Pushpe’s quest for culture in the times of civil

war and its aftermath. He fuses the sublime and the bizarre, the

innocuous and the injurious, the colorful and the banal to engender a

sense of sarcasm. Anoli Perera, another towering artist from the “1990s

trend” noted, “the glossy decorative picture frames around these

canvases depicts the violence which has been contradictorily elevated

into the level of fervor. It also talks about the violence and cruelty

that have been reinterpreted and simplified as unavoidable circumstances

by society that is in a grandiose fervor. Pushpe’s work becomes

important particularly in the post-war situation where already, the

society has started to forget the recent violent past, and artists have

begun to move away from political and interventionist themes”.

In the artistic quest for culture, Pushpe combines the traditional and

the contemporary. The motif of knots borrowed from the woodcarvings in

the Ambekka Devalaya (shrine) in Kandy surfaces in his work, ‘Barbed

Wire.’ The knotty barbs in a frame of normal unsettle the usual grammar

of viewership and art-appreciation. Besides, Pushpe scatters fine dots

in most of his works to symbolize his lineage to the vocation of

woodcarving by professional traditional carpenters in Sri Lanka. And he

does not shy away from adopting mundane symbols of violence either. His

work titled ‘Excavation’ puts burnt tyres in the center of the canvas to

deliver a comment on the consequences of extreme political violence. He

expresses a sense of disarming sarcasm in his series titled, ‘Goodwill

Hardware’ in which plastic-covered barbed wire appear in intriguing

patterns. And, to top it all, he toys with another symbolism in his work

titled, ‘Wall Plug’with strokes of his brush creating a colorful pond

with the famous Lankan

flower Niyangala (Gloriosa Superba/ Glory Lily/Poison Flame).

The beautiful flowers have poisonous roots, which Pushpe had seen being

consumed by the distressed in the Lankan countryside to commit suicide.

Most of the other works by Pushpe persist with the juxtapositions of

opposites, mixing of the innocent and the violent. One could perhaps end

up hearing the sardonic snigger of the artist while browsing through

Pushpe’s works.

In Nutshell4

Through systematic research on the artworks of“1990s trend”, Sasanka

Perera presented an anthropological interpretation for this genre of

work in his book, Violence and Burden of Memory: Remembrance and Erasure in Sinhala Consciousness.

He suggested that the artists representing this trend employ their

personal and public memory to offer a distinct sense of recent political

and social history in contemporary Sri Lanka. Pushpe is squarely in the

midst of this trend and the politics it represents. Among many other

artists following this trend, Pushpe creates his own idea of Sri Lanka

that collapses history and biography, disturbing the fixed notions of

history, politics and art.

The author teaches sociology at the Department of Sociology, South Asian University, New Delhi and has research interests in art and performance in Sri Lanka, India and Bangladesh.