A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Friday, December 1, 2017

Cancer drug offers tantalising hope for HIV cure

Patient given nivolumab, a new generation cancer drug, shown to have a reduced reservoir of dormant HIV cells and a boosted immune response

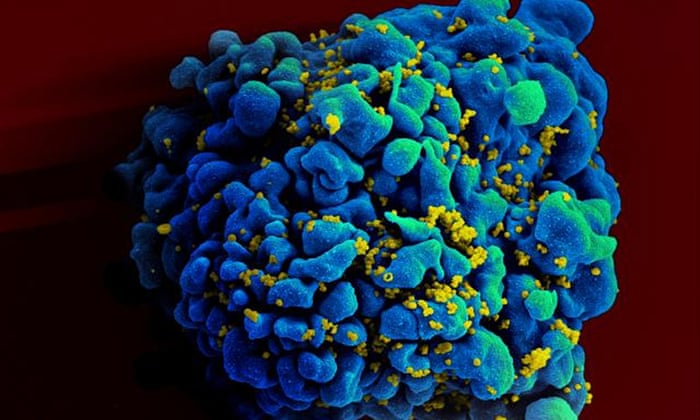

An electron microscope image showing an H9 T cell, blue, infected with HIV, yellow. Photograph: AP

Nicola Davis and agencies-Friday 1 December 2017 00.05 GMT

A new generation cancer drug has raised hopes for those living with HIV after it was found to reduce the reservoir of dormant HIV cells in the body and boost the immune response of a patient.

Doctors say the effect the cancer drug nivolumab appeared to have on the patient offers a tantalising hope that it might provide a way to eradicate the virus from patients.

“This first report of a successful depletion of the HIV reservoirs opens new therapeutic perspectives towards an HIV cure,” the authors of the study write in a letter to the journal Annals of Oncology.

The results are based on findings from a 51-year-old man who had HIV since 1995, and was being treated for lung cancer. After relapsing less than six months after surgery and first-line chemotherapy, he was given the drug nivolumab.

The man then showed a dramatic reduction in reservoirs of HIV-infected cells and increased activity from CD8 “killer” T-cells, a key immune system attack weapon.

“This is the first demonstration of this mechanism working in humans. It could have implications for HIV patients, both with and without cancer, as it can work on HIV reservoirs and tumour cells independently,” said Prof Jean-Philippe Spano, head of the medical oncology department at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital AP-HP in Paris, who led the research. “The absence of side effects in this patient is also good news, and suggests this could be an optimum treatment for HIV-infected patients with cancer.”

But, the team also urge caution, noting that in another patient with HIV where nivolumab was administered there was no drop in the reservoir of dormant cells, while they also note the need to study the toxicity of such drugs in those with HIV.

The drug appears to have the effect of “waking up” white blood cells that are infected with HIV but which are lying low in reservoirs around the body and are not producing HIV. In this state the cells are unable to be attacked by anti-retroviral therapy or the immune system, but when reactivated – and the cells start to produce HIV – they can be.

“Increasingly, researchers have been looking into the use of certain drugs that appear to re-activate the latent HIV-infected cells,” said Spano. “This could have the effect of making them visible to the immune system, which could then attack them.”

If the reservoirs are cleared of dormant infected cells, patients could potentially be cured.

The patient, the team note, has been given 31 injections of nivolumab, administered every 14 days since December 2016. While the man’s HIV levels initially increased, they then dropped and the activity of certain T-cells, including CD8 “killer” T-cells, rose.

By 120 days after treatment began the team say a dramatic and sustained drop in the levels of dormant infected cells was observed.

Experts warn it is too soon to celebrate, noting that it was not clear if the reservoirs would regrow, and that results from other cancer patients with HIV who had been given nivolumab were as yet unreported.

Prof Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said the caution was merited. “We need larger randomised trials to see if this or similar anti-cancer drugs might have a notable effect on the HIV reservoir,” he said. “Until we have such data, talks of cure are premature, but it could lead to new approaches in dealing with HIV.”

The news comes on the same day that a new study into a vaccine against HIV is launched, covering countries including South Africa, Malawi and Zimbabwe. The trial, which involves 2,600 sexually active women followed up over three years, will explore the efficacy of a placebo compared to a vaccine based on two shots and which is designed to provide protection against multiple strains of HIV.

Another boost comes from the New England Medical Journal, which bears further good news, revealing that a US-funded programme to prevent HIV is having a positive effect in Uganda’s rural Rakai District.

The approach, which included making anti-HIV drugs freely available to those with the virus as well as offering condoms, advice and voluntary male circumcision, led to a 42% drop in the rate of new HIV infections between the start of the programme in the early 2000s and 2016.