A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Friday, February 1, 2019

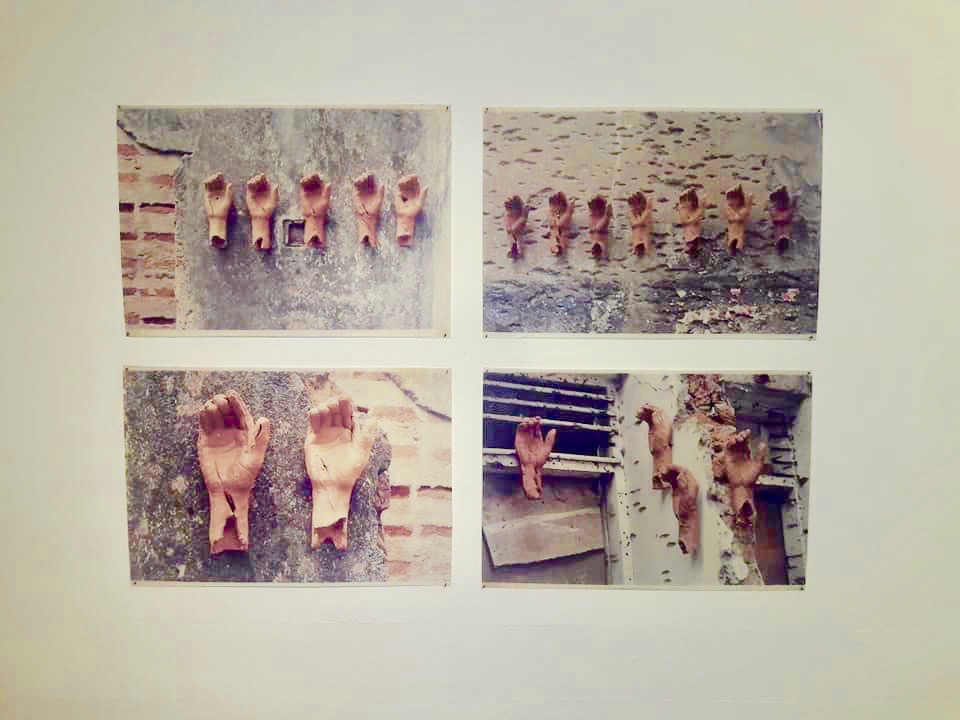

The Days We Screamed

01/31/2019

Yes, we screamed. Mostly out of fear. At times, in joy when the opposing

side faced more loss than us. Lives were taken for granted, numbers of

the fallen mattered much more than lives saved, on both sides. There

were arguments, hate speech even among friends. This emotion was

reflected in the art scene as well. The exhibition “The days we Screamed” brings together paintings and artworks by then young artists who gave artistic expression to the period we lived through.

Initially artists like ACGS Amarasekara who followed the Victorian style

mainly concentrated on landscape and portraits. This trend underwent a

drastic change with the emergence of the “43 group” who introduced

Parisian modernity into Sri Lankan art. However, the art remained

figurative and representational in nature. The subject matter dealt by

the members of the ’43 group was similar to that of their predecessors –

landscapes, portraits and village scenery.

This situation underwent a change with the emergence of H.A. Karunaratne

as an influential artist with his skills acquired from New York. This

effect was witnessed in the 1960’s as the non-figurative tradition of

painting established itself as a way of expressing “spirituality” in Sri

Lankan modern art. This trend had great appeal among the people who

were conditioned by the Buddhist philosophy. Though Karunaratne’s art

practice had great relevance to Sri Lankan context in terms of its

spiritual inclination, it failed to reflect the increasing anxiety and

stresses that was gradually engulfing the Sri Lankan social life.

In the early 1970’s Sri Lankan political landscape started changing with

violence becoming an integral part of society and politics. The first

JVP insurrection of the early 1970s followed by post-election violence

in 1977 and the racial riots of the late 70’s foretold the violence that

was to be unleashed over this island nation in the years to come.

Though in the field of theatre these gradual changes were assimilated,

visual artists remained seemingly immune to all the violence that was

creeping into social life in Sri Lanka.

The early 1980s saw the worsening of ethnic divides and the start of

armed conflict between the JVP, the LTTE and the state. Even in this

political turmoil, the art of the 1980s did not reflect the changing

socio-political environment. However, a younger generation of students

who were witnessing all these changes came to the forefront in the early

90’s. Jagath Weerasinghe’s 1992 exhibition “Anxiety” marked a turning

point in the visual art scene in Sri Lanka.

With this, a young generation of artists who were independent, flexible

and energetic started using ancient and contemporary idioms with social

consciousness. Their art showed the possibility of making art with

multiple layers of cultural and social meaning. In their hands art

assumed new dimensions, beyond being a medium of pure entertainment and

enjoyment.

This period also introduced new forms of expression in visual arts which

were hitherto unknown to the gallery-going public of Sri Lanka.

Installation art and performance art became powerful medium for these

artists to express their ideas.

Artists who were at the forefront of this change included Jagath

Weerasinghe, Chandraguptha Thenuwara, Kingsley Gunatilake, Anoli Perera,

Muhammad Cader, Godwin Constantine, Pradeep Chandrasiri, Pushpakumara

Koralagedara, Bandu Manammperi and T Shanaathanan. There were younger

artists who followed the same lines later.

Jagath Weerasinghe’s paintings centred mainly around distorted male

figures expressing anguish and despair of the period. His exhibition

“Yantragala” used traditional motifs to express contemporary issues. His

innovative approach in art inspired many young artists and art

students.

Thenuwara’s art practice consisted of socially and politically

integrated subject matters. His art works reflect political conflict,

disasters, and the social and economic hardship our people have gone

through and are still going through. Thenuwara’s life experiences along

with his training in Moscow moulded him into a socially engaged art

activist. His camouflage painting and barrel installations have become

unique symbols of Sri Lankan ethnic war.

One of the notable female artists from this period is Anoli Perera.

Though Sri Lanka has a long history of producing many leading female

artists Anoli stands out in fusing ancient and modern idioms to express

the double burden (domestic and political) experienced by Sri Lankan

women.

Kingsley Gunatilake has used his exuberant palate to produce

Greenbergian-type canvases. However, his strength lies in his powerful

installation work. Kingsley can be regarded as a unique artist who used

the maximum expressive potential of installation art in Sri Lanka.

The art scene of the 1990s also saw the emergence of performance art.

The author’s first performance “Broken Palmyrah” was in 1994. This trend

was followed by Bandu Mannamperi and other younger artists later.

Editor’s Note: “The

Days We Screamed” is an exhibition which brings together art work by

this generation of artists. This exhibition is at the Theertha “Red Dot

Gallery” in Borella, and will be open to the public from the 26th of January to the 1st of February.