A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Friday, March 15, 2019

India, Pakistan and the changing rules of engagement: here’s what you need to know

India’s airstrikes caused some damage inside Pakistan. AMIRUDDIN MUGHAL/AAP

India’s airstrikes caused some damage inside Pakistan. AMIRUDDIN MUGHAL/AAP

More than 40 Indian security staff lost their lives in a suicide attack on

February 14, 2019 in the Pulwama region of Indian-administered Kashmir.

The Pakistan-based Islamist militant group Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM)

claimed responsibility for the attack.

Twelve days later, India launched air strikes against JeM training camps in Balakot, Pakistan. India claimed the strikes inflicted significant damage on infrastructure and killed militant commanders, while avoiding civilians.

India said the strikes were “pre-emptive”, based on intelligence that

JeM were planning more suicide attacks in Indian territory. Pakistan

denied India’s claims, both about the damage done by their airstrikes

and that Pakistan was planning further attacks.

But Pakistan retaliated with an airstrike on what it termed a

“non-military installation” in the Indian controlled region of Kashmir.

In the ensuing skirmish with the Indian Air Force, an Indian jet was

downed and a pilot captured.

These events, in the disputed territory of Kashmir, have brought

international attention to the prospect of a nuclear confrontation

between India and Pakistan. But why is the decades-long conflict heating

up again, and why now?

History of Kashmir

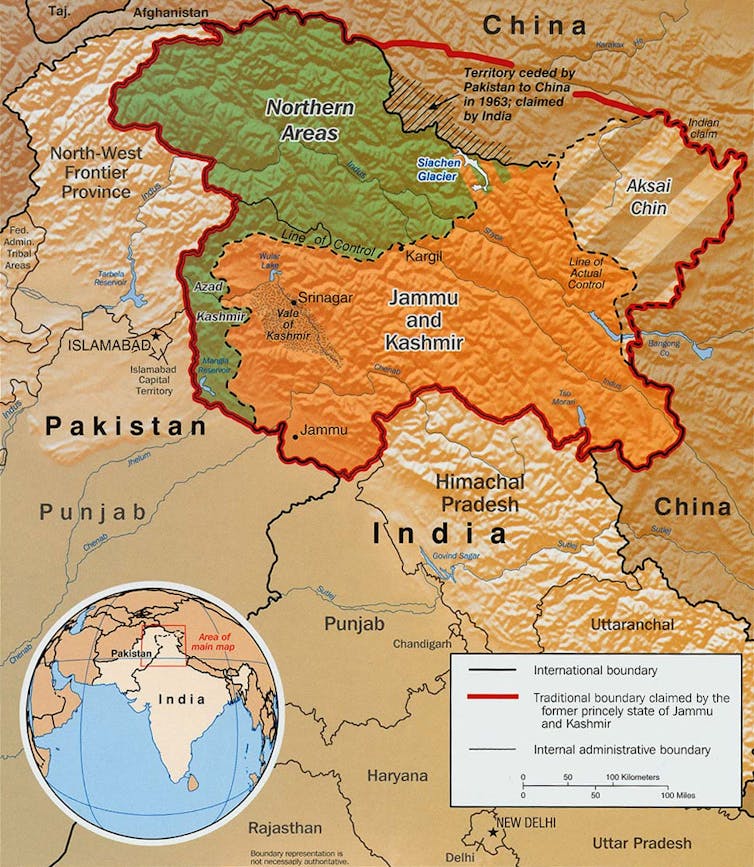

India and Pakistan have been involved in a territorial dispute over

Kashmir for decades. The roots of the conflict lie in the partition of

British India in 1947, which created the secular state of India and the

Muslim state of Pakistan.

The idea behind the partition was for Muslim-majority regions to become a

part of Pakistan. But Kashmir was complicated. Although a

Muslim-majority state, it was ruled by a Hindu king.

He decided to accede to India in October 1947. This was unacceptable to

Pakistan, which launched a war in 1948 to capture Kashmir by force.

A result of the war was a UN-mediated ceasefire line. This divided

Kashmir into Indian-administered “Jammu and Kashmir” (J&K) – which

constituted two-thirds of the territory – and Pakistan-administered

“Azad (free) Kashmir”, which was one-third of the territory.

While the 1948 ceasefire brought an end to the fighting, Kashmir’s

status remained unresolved and Pakistan continued to contest the

territorial boundaries. India granted J&K constitutional autonomy,

while the Pakistan-administered region was a self-governing entity.

View from Pakistan

Kashmir is central to Pakistan’s national identity as a Muslim state,

and therefore it represents unfinished business after the 1947

partition.

Pakistan launched another war against India in 1965, which caused

thousands of casualties on both sides. Hostilities between the two

countries ended after a diplomatic intervention by the Soviet Union and

the United States and a UN-mandated ceasefire.

The 1965 war, the 1971 Indian intervention in Pakistan’s civil war, and

the subsequent creation of Bangladesh led to more changes to the

territorial borders in Kashmir. The ceasefire line is now designated as

the Line of Control (LoC).

Since the 1990s, Pakistan has supported militant groups such as the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) to attack Indian security forces and civilians.

View from India

Kashmir has also been central to India’s national narrative of unity in diversity propagated by leaders of the independence movement, Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi. Indian leaders have often projected the accommodation of a Muslim majority state in the J&K region as proof of Indian secular democracy.

India’s official position considers

the whole of undivided Kashmir as a part of India. And India has not

consistently upheld J&K’s constitutionally-guaranteed autonomy.

Political instability in the state has been compounded by interference

from the Indian government. Indian armed forces in the area have often

used force against civilians.

In the 1990s, this led to a mass uprising and insurgency among the

Kashmiri population in India. Pakistan exploited this discontent,

offering arms, training and funds to both Pakistan-based and local

Kashmiri militants.

The insurgency in Indian Kashmir eased in 2003, with a ceasefire and the

initiation of an India-Pakistan peace process that led to a relative

period of calm.

The peace process came to an end after the 2008 Mumbai terrorist

attacks, carried out by the LeT. But India’s policy of strategic

restraint and pressure on Pakistan by the United States to address

militancy prevented a worsening of hostilities.

A new government came to power in India in 2014, led by the Hindu

nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. The leadership’s approach to

Pakistan and Kashmir has been significantly different from

the previous administration, with more emphasis on curbing dissent in

J&K and using pre-emptive strikes across the LoC against militant

groups in Pakistan’s territory.

Local discontent in Indian Kashmir has also led to an increase in

militancy since 2014 with more Pakistani support and a combination of

rising local recruitment and an influx of foreign militants.

What does this mean?

The rules of engagement between India and Pakistan are changing. India’s

“pre-emptive” air strikes in February were a significant shift away

from the previous policy of strategic restraint. This is the first time

since the dispute emerged that India has targeted militants inside

Pakistani territory.

Pakistan chose to escalate tensions further, a move that had previously

been prevented by the US. Pakistani Prime Minister, Imran Khan, has

reiterated his desire for dialogue with India. But ceasefire violations

across the LoC and the international border have continued unabatedsince February 14k, with both sides reporting civilian casualties.

Diplomatic pressure from the UN and the rest of the international

community has forced the Pakistani government to ban some militant

groups. Yet, it continues to deny that JeM is active in Pakistan.

Meanwhile, tensions with Pakistan are playing well into Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s promotion of

being a “strong leader”, capable of protecting the country from its

enemies. This is all part of the strategy leading up to the coming

elections.

Read more: Kashmir: India and Pakistan's escalating conflict will benefit Narendra Modi ahead of elections

The escalatory responses by both governments have shown the actions of

the two countries are becoming more difficult to control, particularly

with the United States’ lack of involvement in defusing tensions as it

disengages from the region.