A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Wednesday, May 1, 2019

A symbol of slavery — and survival

Angela’s arrival in Jamestown in 1619 marked the beginning of a subjugation that left millions in chains. The sun sets on the James River in April, seen from Historic Jamestown in Williamsburg, Va. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

The sun sets on the James River in April, seen from Historic Jamestown in Williamsburg, Va. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

By DeNeen L. Brown-

APRIL 29, 2019

By the time Angela was brought to Jamestown’s muddy shores in 1619, she had survived war and capture in West Africa, a forced march of more than 100 miles to the sea, a miserable Portuguese slave ship packed with 350 other Africans and an attack by pirates during the journey to the Americas.

“All of that,” marveled historian James Horn, president of the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, “before she is put aboard the Treasurer,” one of two British privateers that delivered the first Africans to the English colony of Virginia.

Now, as the country marks the 400th anniversary of the arrival of those first slaves, historians are trying to find out as much as possible about Angela, the first African woman documented in Virginia.

They see her as a seminal figure in American history — a symbol of 246 years of brutal subjugation that left millions of men, women and children enslaved at the start of the Civil War

She is listed in the 1624 and 1625 census as living in the household of Capt. William Pierce, first as “Angelo a Negar” and then as “Angela Negro woman in by Treasurer.” By then, she had survived two other harrowing events: a Powhatan Indian attack in 1622 that left 347 colonists dead and the famine that followed.

Yet little is known about her beyond those facts.

[The Dawn of American Slavery: Jamestown 400 special report]

“It is presumed she was youngish — maybe in her early 20s,” said Cassandra Newby-Alexander, a history professor at Norfolk State University and co-author of “Black America Series: Portsmouth, Virginia.” “Angela was her Anglicized name. We don’t know what her original name was.”

“If they find the remains, we can know how old she was when she arrived,” Newby-Alexander said.

“Did she have children? What did she die of? We will know more about this person, and we can reclaim her humanity.”

The Angela Site where excavation work is taking place at Historic Jamestown. (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

The transatlantic slave trade was already more than a century old and thriving when the first Africans reached Virginia.

“The trade is full-blown in 1619,” said Daryl Michael Scott, a Howard University history professor. The Portuguese controlled much of the market, transporting “huge numbers of Africans taken from what becomes Portuguese Angola.”

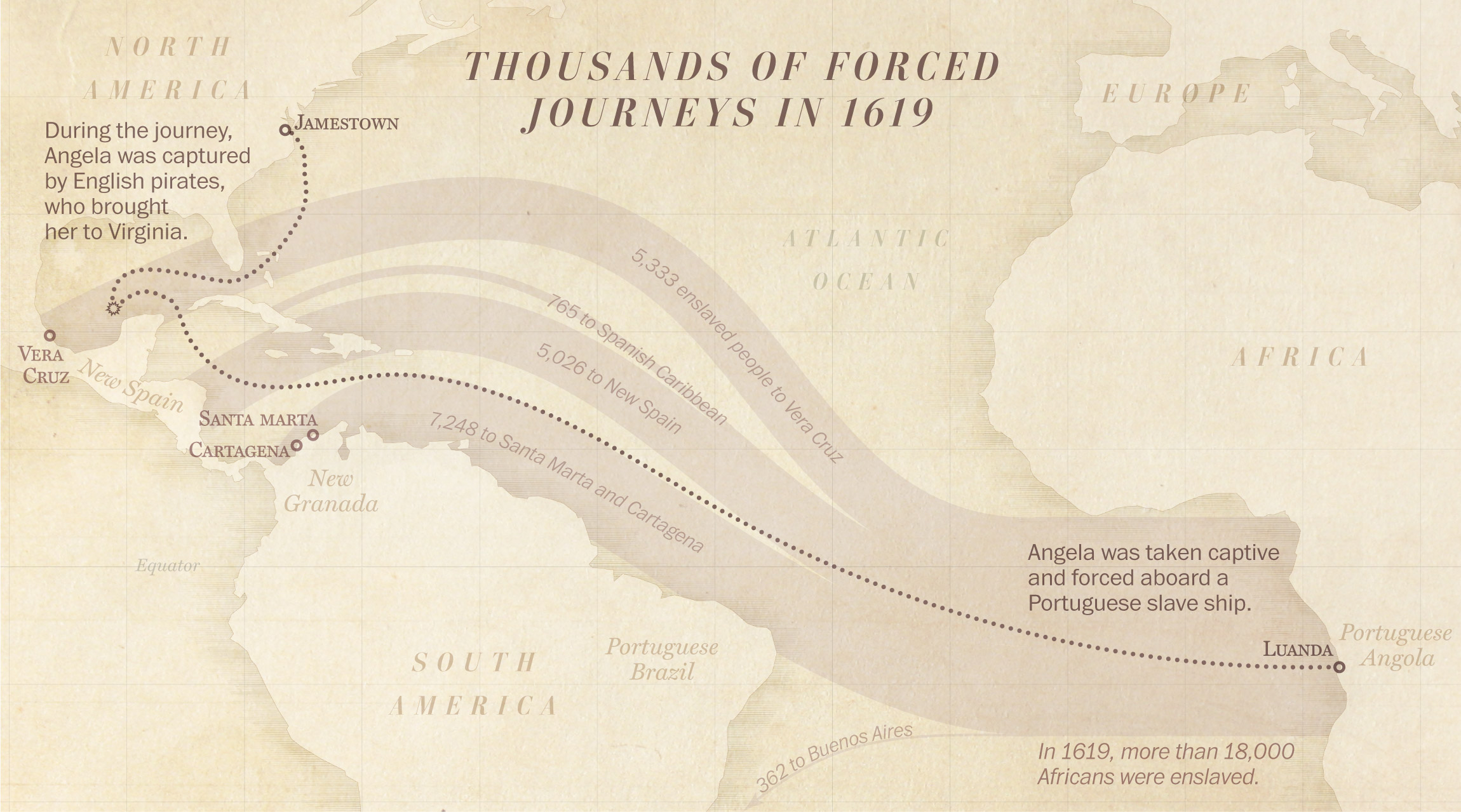

Between 5,000 and 8,000 people from Kongo, Ndongo and other parts of West Africa were being shipped each year to Portuguese and Spanish colonies in the Americas. The total number of Africans captured and transported to the Americas between 1501 and 1867 would eventually grow to more than 12.5 million.

[Scientific racism: a brief history of the phony theories that perpetuate white supremacy]

Angela was taken captive in 1619 during a war in Kongo. She was forced aboard a slave ship, the San Juan Bautista, in Luanda, then a bustling slave-trading port on the coast of West Africa, according to Jamestown Rediscovery. The ship was headed for Vera Cruz, on the coast of Mexico.

“The ship was overcrowded,” Horn said. “It suffered horrible mortality on the voyage to Vera Cruz.” More than 120 Africans aboard died en route.

In the middle of passage, the slave ship was attacked by two English pirate ships — the Treasurer and the White Lion. The pirates climbed aboard the Bautista, hoping to find a bounty of gold.

Instead, they found humans, desperate people. The pirates took 60 or so Africans, splitting them between the White Lion and the Treasurer. Historians surmise that the pirates took the young, healthiest captives. Angela was among them.

“I’ve got no evidence that she was young,” Horn said. “I base it on the general model that slavers would try to take the younger people, including children, women and males they would get the most money for. That is a chilling aspect of the slave trade. People are being treated like livestock. The capability of women to have children was in slavers’ minds. To survive a journey like that, my own sense is she was young and possibly very young. Where there is no evidence, it is fair to speculate.”

The arrival of the White Lion was reported by colonist John Rolfe, who is best known for marrying Pocahontas in 1614. He wrote: “About the latter end of August, a Dutch man of Warr of the burden of a 160 tunes arrived at Point-Comfort, the Comandors name Capt Jope, his Pilott for the West Indies one Mr Marmaduke an Englishman. … He brought not any thing but 20. and odd Negroes, w[hich] the Governo[r] and Cape Merchant bought for victuall[s].”

The Treasurer was next to arrive. A number of historical accounts reported that the Treasurer turned around quickly after being anchored near Point Comfort, avoiding an order by the governor to detain the ship and question its captain “about his involvement in acts of piracy in the Spanish Indies,” according to Horn.

The Treasurer, these accounts reported, headed for Bermuda before returning to Virginia. But Horn says new evidence he found in December while researching archives in London show that the Treasurer arrived in Virginia four days after the White Lion with 28 to 30 Africans that had been captured on the Portuguese slave ship.

One of those two or three Africans was Angela, who wound up in the household of Pierce.

“The majority of the Angolans were acquired by wealthy and well-connected English planters including Governor Sir George Yeardley and the cape, or head, merchant, Abraham Piersey,” according to Jamestown Rediscovery. “The Africans were sold into bondage despite Virginia having no clear-cut laws sanctioning slavery.”

But that would change.

[‘The haunted houses’: Legacy of Nat Turner’s slave rebellion lingers, but reminders are disappearing]

TOP: Historic Jamestown in Williamsburg. BOTTOM LEFT: Remnants of the

slave ship Sao Jose on display in March at the National Museum of

African American History and Culture in Washington. BOTTOM RIGHT: Lee

McBee, supervising archaeologist at the Angela Site, works on a piece of

pottery in March. (Photos by Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

Angela’s arrival coincided with another milestone in American history: the meeting of the first General Assembly in Jamestown’s newly built wooden church. The assembly is billed by Jamestown Rediscovery as “the oldest continuous law-making body in the western hemisphere.”

The legislative body was made up of the governor, his four councilors and 22 burgesses elected by every free white male settler in the colony. Its work from July 30 to Aug. 4, 1619, represented the nation’s first experiment with democracy, and its 400th anniversary is being marked this year.

It is a great irony, Horn said, that American slavery and democracy were created at the same time and place.

He said that “1619 gave birth to the great paradox of our nation’s founding: slavery in the midst of freedom. It marked both the origin of the most important political development in American history, the rise of democracy, and the emergence of what would become one of the nation’s greatest challenges: the corrosive legacy of racial discrimination and inequality that has afflicted our society since its earliest years.”

The conditions endured by settlers and enslaved people alike were awful.

The colony, which had been established in 1607, stretched from Point Comfort to what is now Richmond. There were plantations scattered for about 100 miles along the banks of the James River. Jamestown itself probably had a population of about 100.

The colonists had, at one point, nearly been wiped out. In 1609, they were under siege by the Powhatan and facing starvation that led to cannibalism. Capt. John Smith described that horror in a 1624 letter:

“October 1609 — March 1610, there remained not past sixtie men, women and children, most miserable and poore creatures; and those were preserved for the most part, by roots, herbes, acornes, walnuts, berries, now and then a little fish: they that had startch in these extremities, made no small use of it; yea even the very skinnes of our horses.

"Nay, so great was our famine, that a Salvage we slew and buried, the poorer sort tooke him up againe and eat him; and so did divers one another boyled and stewed with roots and herbs: And one amongst the rest did kill his wife, powdered [i.e., salted] her, and had eaten part of her before it was knowne; for which hee was executed, as hee well deserved: now whether shee was better roasted, boyled or carbonado’d [i.e., grilled], I know now; but of such a dish as powdered wife I never heard of.”

[Anthony and Mary Johnson were pioneers on the Eastern Shore whose surprising story tells much about race in Virginia history]

Angela lived through what is called the “Second Starving Time.” “Many people died during the Second Starving Time,” Horn said. “There isn’t enough corn to support” the large numbers of arriving settlers. “You have a period where food prices, particularly for Indian corn, are astronomical. A lot of poor servants and white indentured servants perished or died of disease. It is a grim period.”

Angela probably survived because she lived on the plantation of Pierce, one of the wealthiest men in the colony. “We know some Africans died during that period,” Horn said. “We know there were 32 Africans living in the colony in 1620. We know only 23 Africans were living in the colony in 1625.”

But by 1626, Angela disappears from the census records. Her fate is unknown.

The 1624-1625 Jamestown census lists an “Angelo a Negar.” (Matt McClain/The Washington Post)

Jamestown Rediscovery recently released an illustration depicting

Angela, circa 1625, standing on the banks of the James River as ships

are anchored in the background.“We wanted to provide a setting for Angela that reflected what was going on in Jamestown at the time,” Horn said. “She would have been living in Jamestown six years around 1625, which is a good date for the drawing. She certainly would have been dressed in English clothing. The dockside, it is quite possible she would have spent time down there, which was a few yards from the Pierce house.”

Horn said the artist wanted to give Angela a sense of dignity and autonomy. She is not dressed in rags.

“Her clothing would not have been fancy,” Horn said, “but everyday working clothing. Essentially, she is dressed in the clothing of a working young woman for the Pierce family.”

The illustration allows viewers to fill in the gaps in history, paying due to the colony’s first documented African woman.

“I see her not so much as a kind of Eve figure for Africans,” Horn said. “There were other Africans in the colony in Virginia. I see the significance of Angela being able to put a name to her and identify her in a place.”

And to remind Americans 400 years later what she managed to survive.

Graphics by Lauren Tierney and Armand Emamdjomeh. Map and chart data sourced from Slave Voyages.