A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Friday, May 31, 2019

How we traced ‘mystery emissions’ of CFCs back to eastern China

May 22, 2019 1.23pm EDT

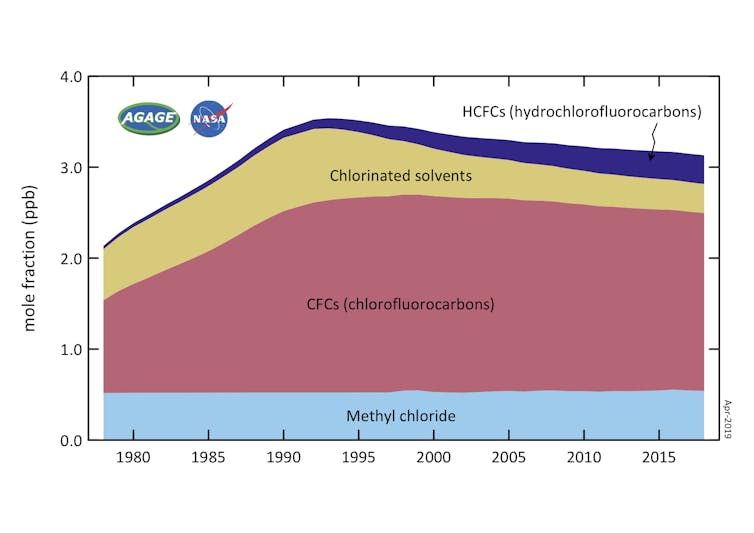

Since being universally ratified in the 1980s, the Montreal Protocol –

the treaty charged with healing the ozone layer – has been wildly

successful in causing large reductions in emissions of ozone depleting

substances. Along the way, it has also averted a sizeable amount of

global warming, as those same substances are also potent greenhouse

gases. No wonder the ozone process is often held up as a model of how

the international community could work together to tackle climate change.

However, new research we have published with colleagues in Natureshows

that global emissions of the second most abundant ozone-depleting gas,

CFC-11, have increased globally since 2013, primarily because of

increases in emissions from eastern China. Our results strongly suggest a

violation of the Montreal Protocol.

A global ban on the production of CFCs has been in force since 2010, due

to their central role in depleting the stratospheric ozone layer, which

protects us from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Since global

restrictions on CFC production and use began to bite, atmospheric

scientists had become used to seeing steady or accelerating year-on-year

declines in their concentration.

But bucking the long-term trend, a strange signal began to emerge in 2013: the rate of decline of the second most abundant CFC was slowing.

Before it was banned, the gas, CFC-11, was used primarily to make

insulating foams. This meant that any remaining emissions should be due

to leakage from “banks” of old foams in buildings and refrigerators,

which should gradually decline with time.

But in that study published last year, measurements from remote monitoring stations suggested

that someone was producing and using CFC-11 again, leading to thousands

of tonnes of new emissions to the atmosphere each year. Hints in the

data available at the time suggested that eastern Asia accounted for

some unknown fraction of the global increase, but it was not clear where

exactly these emissions came from.

Growing ‘plumes’ over Korea and Japan

Scientists, including ourselves, immediately began to look for clues

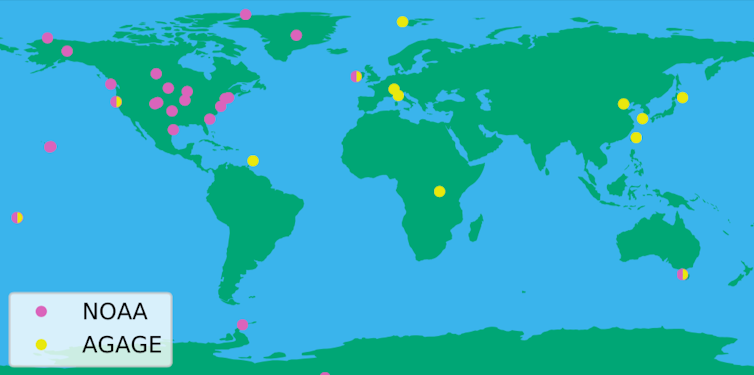

from other measurements around the world. Most monitoring stations,

primarily in North America and Europe, were consistent with gradually

declining emissions in the nearby surrounding regions, as expected.

But all was not quite right at two stations: one on Jeju Island, South Korea, and the other on Hateruma Island, Japan.

These sites showed “spikes” in concentration when plumes of CFC-11 from

nearby industrialised regions passed by, and these spikes had got bigger

since 2013. The implication was clear: emissions had increased from

somewhere nearby.

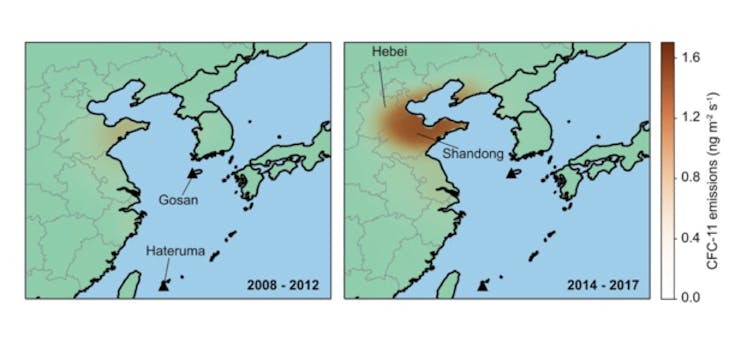

To further narrow things down, we ran computer models that could use

weather data to simulate how pollution plumes travel through the

atmosphere.

From the simulations and the measured concentrations of CFC-11, it

became apparent that a major change had occurred over eastern China.

Emissions between 2014 and 2017 were around 7,000 tonnes per year higher

than during 2008 to 2012. This represents more than a doubling of

emissions from the region, and accounts for at least 40% to 60% of the

global increase. In terms of the impact on climate, the new emissions

are roughly equivalent to the annual CO₂ emissions of London.

The most plausible explanation for such an increase is that CFC-11 was

still being produced, even after the global ban, and on-the-ground

investigations by the Environmental Investigations Agency and the New York Times seemed

to confirm continued production and use of CFC-11 even in 2018,

although they weren’t able to determine how significant it was.

While it’s not known exactly why production and use of CFC-11 apparently

restarted in China after the 2010 ban, these reports noted that it may

be that some foam producers were not willing to transition to using

second generation substitutes (HFCs and other gases, which are not

harmful to the ozone layer) as the supply of the first generation

substitutes (HCFCs) was becoming restricted for the first time in 2013.

Bigger than the ozone hole

Chinese authorities have said they will “crack-down” on

any illegal production. We hope that the new data in our study will

help. Ultimately, if China successfully eliminates the new emissions

sources, then the long-term negative impact on the ozone layer and

climate could be modest, and a megacity-sized amount of CO₂-equivalent

emissions would be avoided. But if emissions continue at their current

rate, it could undo part of the success of the Montreal Protocol.

While this story demonstrates the critical value of atmospheric

monitoring networks, it also highlights a weakness of the current

system. As pollutants quickly disperse in the atmosphere, and as there

are only so many measurement stations, we were only able to get detailed

information on emissions from certain parts of the world.

Therefore, if the major sources of CFC-11 had been a few hundred

kilometres further to the west or south in China, or in unmonitored

parts of the world, such as India, Russia, South America or most of

Africa, the puzzle would remain unsolved. Indeed, there are still parts

of the recent global emissions rise that remain unattributed to any

specific region.

When governments and policy makers are armed with this atmospheric data,

they will be in a much better position to consider effective measures.

Without it, detective work is severely hampered.