A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Saturday, November 30, 2019

How your big brain makes you human

by Suzana HerculanoHouzel, -November 27, 2019

Here’s something new to consider being thankful for at the dinner table:

the long evolutionary journey that gave you your big brain and your

long life.

Courtesy of our primate ancestors that invented cooking over a million years ago, you are a member of the one species able to afford so many cortical neurons in its brain. With them come the extended childhood and the pushing century-long lifespan that together make human beings unique.

All these bequests of your bigger brain cortex mean you can gather four

generations around a meal to exchange banter and gossip, turn information into knowledge and even practice the art of what-not-to-say-when.

You may even want to be thankful for another achievement of our neuron-crammed human cortices: all the technology that

allows people spread over the globe to come together in person, on

screens, or through words whispered directly into your ears long

distance.

I know I am thankful. But then, I’m the one proposing that we humans revise the way we tell the story of how our species came to be.

Brains made of cells, but how many?

Back when I had just received my freshly minted Ph.D. in neuroscience

and started working in science communication, I found out that 6 in 10

college-educated people believed they only used 10% of their brains. I’m glad to say that they’re wrong: We use all of it, just in different ways at different times.

The myth seemed to be supported by statements in serious textbooks and scientific articles that “the human brain is made of 100 billion neurons and

10 times as many supporting glial cells.” I wondered if those numbers

were facts or guesses. Did anyone actually know that those were the numbers of cells in the human brain?

No, they didn’t.

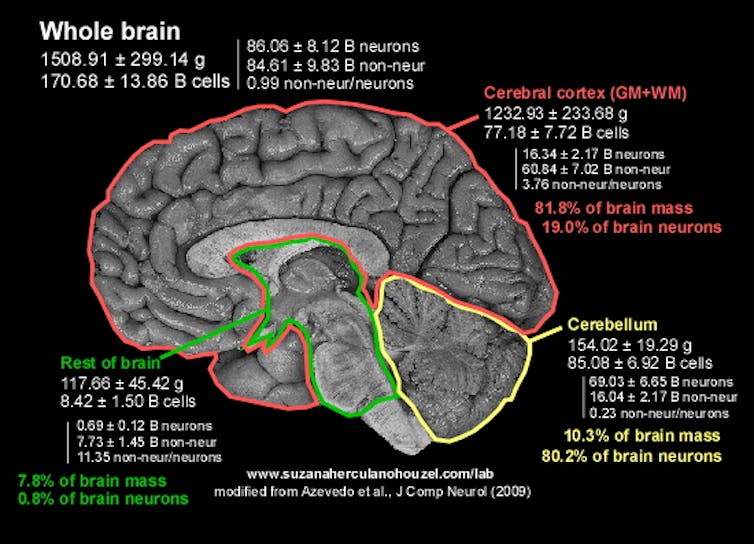

Neuroscientists did have a rough idea. Some estimates suggested 10 to 20

billion neurons for the human cerebral cortex, others some 60 to 80

billion in another region called the cerebellum. With the rest of the

brain known to be fairly sparse in comparison, the number of neurons in

the whole human brain was definitely closer to 100 billion than to just

10 billion (far too little) or 1 trillion (way too many).

But there we were, neuroscientists armed with fancy tools to modify

genes and light up parts of the brain, still in the dark about what

different brains were made of and how the human brain compared to

others.

Suzana Herculano-Houzel, CC BY-ND

Counting up neurons in brain soup

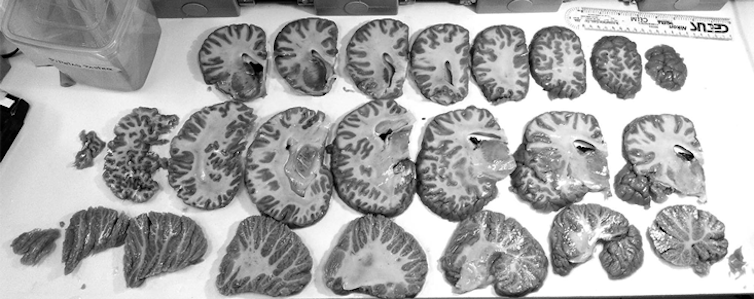

So I devised a way to easily and rapidly count how many cells a brain is made of. I spent 15 years collecting brains and then turning them into soup that I examined under the microscope. That’s how I got the hard numbers.

Drawings by Lorena Kaz, CC BY-ND

As it turned out, there are many ways to put brains together: Primates like us have more neurons in the cerebral cortex than

most other mammals, no matter the size of the brain. A brain can be

large but made of relatively few neurons if those neurons are huge, like

in an elephant; primate neurons are small, and bird neurons are even

tinier, so even the smallest bird brains can hide lots of neurons. But never as many as the largest primate brain: ours.

When comparing brains, we care about numbers of neurons in the cortex

because it’s the area of the brain that lets us go beyond the simple

detection and response to stimuli, allowing us to learn from the past

and make plans for the future.

Because neurons are the Lego pieces that build brains and process information, the more cortical neurons a species has,

the more flexible and complex that species’ cognition can be,

regardless of size. And not just that: I recently found that the more

cortical neurons, the longer the species takes to develop into adulthood,

just like it takes longer to assemble a truckload of Legos into a

mansion than a handful into a little house. And for as yet unknown

reasons, along with more cortical neurons comes a longer life.

Getting more cortical neurons thus seems to be a two-for-one bargain: Buy more mental capabilities, and along comes more lifetime to learn to use them.

Suzana Herculano-Houzel, CC BY-ND

Powering all those neurons

If people had kept exclusively eating raw foods, like all other primates do, they would need to spend over nine hours every single day searching, collecting, picking and eating to feed their 16 billion cortical neurons. Forget about discovering electricity or building airplanes. There would be no time for looking at the stars and wondering about what could be. Our great ape cousins, ever the raw foodies, still have at most half as many cortical neurons as we do – and they eat over eight hours per day.

But our ancestors figured out how to cheat nature to get more from less,

first with stone tools and later with fire. They invented cooking and changed human history. Eating is faster and much more efficient, not to say delicious, when food is pre-processed and transformed with fire.

With plenty of calories available in much less time, new generations

gained bigger and bigger brains. And the more cortical neurons they had,

the longer kids remained kids, the longer their parents lived, and the

more the former could learn from the latter, then from grandparents, and

even great-grandparents. Cultures soon flourished. Technology bloomed

and lived on through schooling and science, becoming ever more complex.

With so much culture to share, what makes us modern humans has become about much more than our human biology.

Being born with lots of neurons gives us the potential for a long and

slow life, one where each of our brains gets a chance to be educated by

what the generations before us have learned, and to educate the next

ones. We will remain modern humans so long as we are willing to convene

around dinner tables to celebrate our differences and to share our

hard-earned knowledge, stories of success and failure, our hopes and

dreams.

Suzana Herculano-Houzel is the author of: The Human Advantage: How Our Brains Became Remarkable MIT Press provides funding as a member of The Conversation.

MIT Press provides funding as a member of The Conversation.