A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Tuesday, March 31, 2020

Following the coronavirus money trail

Central banks are printing money on an unprecedented scale. Unless governments act, most of this will end up in the bank accounts of the rich.

Over the past week central banks around the world have started printing

money on an enormous scale to deal with the coronavirus pandemic.

Gary Stevenson-27 March 2020

Gary Stevenson-27 March 2020

In the US, the Federal Reserve has pledged to buy a potentially unlimited amount of government debt. In Europe, the European Central Bank (ECB) has announced a new €750bn Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). And in the UK, the Bank of England has injected £200bn of fresh money into the economy via its quantitative programme.

This begs the question: where will all this money ultimately end up, and who stands to benefit from it? To answer this question, we must first understand the nature of the economic crisis we face.

The coronavirus outbreak and associated economic shutdown has led to an enormous decrease in total society-wide spending. Because one person’s expenditure is another person’s income, this has led to an enormous society-wide decrease in income.

In order to save many desperate people, governments have stepped in and offered to replace much of this income directly from government coffers. Governments will get this money by borrowing from investors through the issuance of bonds. These investors, in turn, will get this money by selling their existing government bonds back to central banks, who are a separate and independent branch of government. Central banks will literally “create” the money electronically, essentially out of thin air, meaning that there will be a large increase in the total amount of money in the system.

So there’s an interesting bit of apparent magic here. Central banks have created a lot of new money, but since that money is being used to directly replace the lost income of workers, nobody’s income has increased. In fact, in most countries the government is not subsidising lost incomes fully, only partially. So many people’s incomes have still fallen overall.

So if the central bank has created a lot of new money, and pushed it into the system, but nobody’s income has gone up, then where did all the money go? This is the magic trick.

The answer is that while nobody’s gross income or total income went up, there is one group whose net income has gone up significantly – and that is the rich.

This is because, whilst all incomes went down or stayed the same, the expenditures of different groups have changed enormously. Remember that the very first change here was a collapse in spending, and it was that fall in spending which first caused the falls in income. These spending reductions are not equal across the economy. For large numbers of people, especially the poorest, most or even all of their spending is on essentials. Outgoings such as rent or mortgage payments,

food, bills and other essentials take up a very large chunk of disposable income for most people. For these people, their spending will barely have fallen, as they will still need to buy all of these things.

So if ordinary working people have not significantly reduced their spending, then where have the huge falls in societal spending come from? The answer is from richer people, for whom almost all of their spending comes in the form of discretionary, non-essential spending.

Of course, we all have some discretionary spending. The difference is that, as we get richer, the essentials become easier to afford, and more of our spending gets spent on non-essentials or luxuries.

The richer you are, the more you spend on holidays, restaurants, theatres and bars (all the industries that are now shut down), and the less, proportionally, you spend on food, rent and bills.

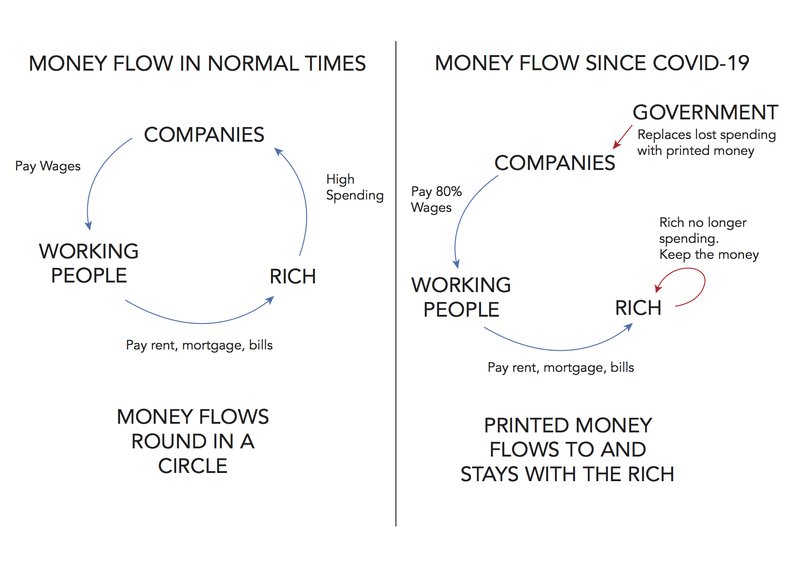

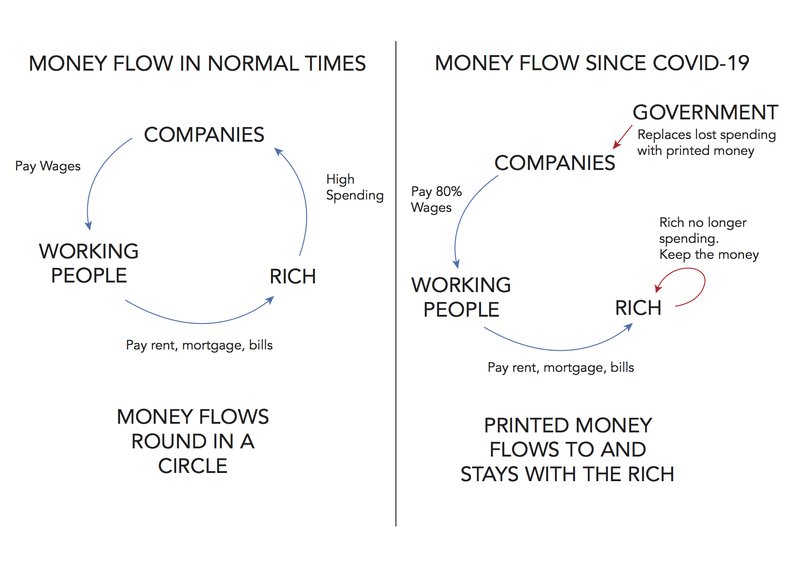

To illustrate this, let’s compare the flow of money through the economy before and after the coronavirus outbreak.

Before the outbreak, the cash flows went like this:

1. The discretionary spending of the rich generated a flow of revenue to companies, who paid wages to working people.

2 Working people then used this money to pay rents, mortgages, food and bills.

3. This money ended up with the owners of housing, the underlying lenders on loans, and the owners of corporations.

Since the outbreak began, things have changed:

1. The rich have cut back on their spending in response to the economic shutdown.

2. This has stopped the flow of wages to working people, which means they cannot pay for their essentials.

3. In order to replace this income, central banks have given money to investors who have lent it to the government (taking a cut), who in turn have given it to working people.

4. Working people are now using this money to pay rents, mortgages, food and bills.

5. As before, money ends up with the owners of housing, the underlying lenders on loans, and the owners of corporations.

Who are the winners and losers here? Working people receive their incomes from the government, although they lose out a bit as their incomes are not fully subsidised. The rich also end up with the money they would have received anyway via rents, interest and corporate incomes. Crucially, however, the spending of the rich has decreased massively. This means that the rich end up profiting as their income has stayed the same but their outgoings have fallen.

At a basic level, the government has created new money to replace the lost spending of the rich, so that working people can continue to pay their bills to the rich. The new money that has been created by central banks ends up accumulating in rich individuals’ bank accounts, as shown in the diagram below.

We should be very, very wary here. Printing money may appear almost as a "magic money tree" that can solve this crisis almost cost-free, with no one taking a big hit to their incomes. But it has very distortionary effects. That money will end up in the hands of the richest via the mechanism described above, meaning that it will directly increase inequality.

Gary Stevenson-27 March 2020

Gary Stevenson-27 March 2020In the US, the Federal Reserve has pledged to buy a potentially unlimited amount of government debt. In Europe, the European Central Bank (ECB) has announced a new €750bn Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). And in the UK, the Bank of England has injected £200bn of fresh money into the economy via its quantitative programme.

This begs the question: where will all this money ultimately end up, and who stands to benefit from it? To answer this question, we must first understand the nature of the economic crisis we face.

The coronavirus outbreak and associated economic shutdown has led to an enormous decrease in total society-wide spending. Because one person’s expenditure is another person’s income, this has led to an enormous society-wide decrease in income.

In order to save many desperate people, governments have stepped in and offered to replace much of this income directly from government coffers. Governments will get this money by borrowing from investors through the issuance of bonds. These investors, in turn, will get this money by selling their existing government bonds back to central banks, who are a separate and independent branch of government. Central banks will literally “create” the money electronically, essentially out of thin air, meaning that there will be a large increase in the total amount of money in the system.

So there’s an interesting bit of apparent magic here. Central banks have created a lot of new money, but since that money is being used to directly replace the lost income of workers, nobody’s income has increased. In fact, in most countries the government is not subsidising lost incomes fully, only partially. So many people’s incomes have still fallen overall.

So if the central bank has created a lot of new money, and pushed it into the system, but nobody’s income has gone up, then where did all the money go? This is the magic trick.

The answer is that while nobody’s gross income or total income went up, there is one group whose net income has gone up significantly – and that is the rich.

This is because, whilst all incomes went down or stayed the same, the expenditures of different groups have changed enormously. Remember that the very first change here was a collapse in spending, and it was that fall in spending which first caused the falls in income. These spending reductions are not equal across the economy. For large numbers of people, especially the poorest, most or even all of their spending is on essentials. Outgoings such as rent or mortgage payments,

food, bills and other essentials take up a very large chunk of disposable income for most people. For these people, their spending will barely have fallen, as they will still need to buy all of these things.

So if ordinary working people have not significantly reduced their spending, then where have the huge falls in societal spending come from? The answer is from richer people, for whom almost all of their spending comes in the form of discretionary, non-essential spending.

Of course, we all have some discretionary spending. The difference is that, as we get richer, the essentials become easier to afford, and more of our spending gets spent on non-essentials or luxuries.

The richer you are, the more you spend on holidays, restaurants, theatres and bars (all the industries that are now shut down), and the less, proportionally, you spend on food, rent and bills.

To illustrate this, let’s compare the flow of money through the economy before and after the coronavirus outbreak.

Before the outbreak, the cash flows went like this:

1. The discretionary spending of the rich generated a flow of revenue to companies, who paid wages to working people.

2 Working people then used this money to pay rents, mortgages, food and bills.

3. This money ended up with the owners of housing, the underlying lenders on loans, and the owners of corporations.

Since the outbreak began, things have changed:

1. The rich have cut back on their spending in response to the economic shutdown.

2. This has stopped the flow of wages to working people, which means they cannot pay for their essentials.

3. In order to replace this income, central banks have given money to investors who have lent it to the government (taking a cut), who in turn have given it to working people.

4. Working people are now using this money to pay rents, mortgages, food and bills.

5. As before, money ends up with the owners of housing, the underlying lenders on loans, and the owners of corporations.

Who are the winners and losers here? Working people receive their incomes from the government, although they lose out a bit as their incomes are not fully subsidised. The rich also end up with the money they would have received anyway via rents, interest and corporate incomes. Crucially, however, the spending of the rich has decreased massively. This means that the rich end up profiting as their income has stayed the same but their outgoings have fallen.

At a basic level, the government has created new money to replace the lost spending of the rich, so that working people can continue to pay their bills to the rich. The new money that has been created by central banks ends up accumulating in rich individuals’ bank accounts, as shown in the diagram below.

We should be very, very wary here. Printing money may appear almost as a "magic money tree" that can solve this crisis almost cost-free, with no one taking a big hit to their incomes. But it has very distortionary effects. That money will end up in the hands of the richest via the mechanism described above, meaning that it will directly increase inequality.

But that’s not all. The rich tend to use excess income to buy houses and other assets, and will likely do so at very low prices in the immediate aftermath of the crisis. This will likely push asset prices up, increasing inequality further.

Governments, meanwhile, will be left largely indebted. The likely outcome of this will be austerity and decreased consumer spending, as both individuals and governments try to balance weakened budgets. Meanwhile, house and asset prices will skyrocket as the rich put their increased net income positions to work.

A very similar dynamic to this occured after the 2008 crisis, which also saw large scale money printing by central banks to replace lost spending by the rich in the economy. This was followed by skyrocketing asset prices, while the real economy and wages stagnated. It is important we do not make these mistakes again.

The most pressing issue at the moment is to provide support for those who need it. In times of crisis, we should be asking the rich to help pay for this response. But instead we are largely billing the poor, while consigning ourselves to a future of austerity, unaffordable housing and increased inequality.

We must therefore urgently urge governments to introduce mechanisms that will ensure that the rich contribute to resolving this crisis, rather than simply profiting from it. The most effective policy would be a one-off emergency wealth tax. This would ensure that the sizable costs of this crisis are borne by those who have the capacity to pay them, as well as avoiding the huge increases in inequality seen after the 2008 crisis.

A one off, emergency crisis demands a one-off, emergency response. We can’t afford to make the poor pay for another crisis.