A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Thursday, September 3, 2020

Are riots counterproductive, and who decides?

Street violence is often blamed for producing a political backlash, but the real picture is more complex.

|

Matteo Tiratelli-1 September 2020

When some of the recent Black Lives Matter protests against the murder of George Floyd ended in riots, the pushback was immediate and predictable: different visions of Martin Luther King’s legacy were fought over, rival interpretations of the Civil Rights Movement were deployed, and contrasting lessons were identified.

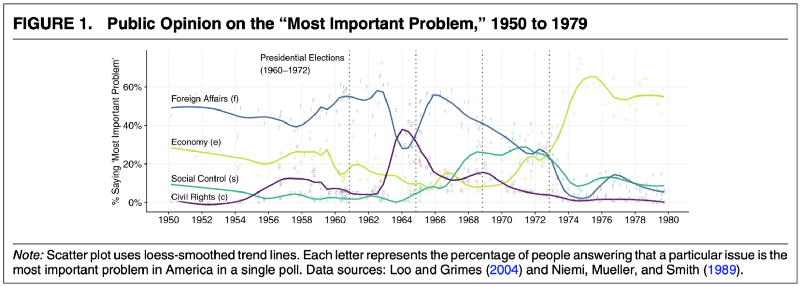

There can be no single interpretation of the turbulent 1960s, but there is much we can learn from historical work on this period. In particular, Omar Wasow’ s recent analysis of the tactics of the Civil Rights Movement makes a provocative argument that “nonviolent” protest helped to shape a national conversation which raised the profile of the civil rights agenda and led to electoral gains for the Democrats in the early 1960s.

By contrast, he argues, rioting in US cities after the assassination of Martin Luther King pushed white Americans towards the rhetoric of ‘law and order,’ causing large shifts among white voters towards the Republican Party and helping Richard Nixon to win the 1968 presidential election shortly thereafter.

This is a controversial argument, even costing political analyst David Shor his job when he recently tweeted about Wasow’s thesis and received an angry response from those who saw it as a “tone-deaf” attack on legitimate protest. At the root of this controversy are important questions about whether framing riots as a ‘tactical choice’ is appropriate, who that framing makes responsible for ongoing racial injustice, and what the fact that we’re having this debate says about people’s views of politics and priorities. As King warned in 1968:

“A riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it America has failed to hear?...it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquillity and the status quo than about justice and humanity.”

But social movements can’t afford to ignore these arguments completely. The idea that violent protests might be risky is not surprising, since in societies that pride themselves on being ‘peaceful,’ riots violate many taken-for-granted liberal values. Wasow’s rigorous, quantitative analysis gives this argument a historical foundation but it also has obvious resonances for today, at a time when President Trump is running for re-election on a ‘law and order’ platform against the background of street protests in cities like Portland and Kenosha.

However, the implications of Wasow’s arguments are not as straightforward as they might appear. One immediate issue concerns his methodology and the size of the effects he estimates. The models reported in Wasow’s paper don’t include any controls for time, which are normally included in statistical analyses to control for general trends affecting society as a whole, trends we assume would have happened anyway.

In an appendix to his paper, Wasow does report some models with a time control, and these significantly reduce the negative effect of rioting on white American opinion. Whether that affects his claim that Nixon would have lost the 1968 presidential election in the absence of riots is difficult to say without further analysis. But leaving the precise size of the effect to one side, it seems plausible to say that violent protests did alienate at least some potential allies of the Civil Rights Movement, and that this could have had significant electoral consequences.

But something else is clear from the public opinion data that Wasow collects. Even during the height of the supposedly “nonviolent” protests of the early 1960s, the civil rights agenda was only momentarily pushed to the front of the national conversation. The sudden leaps that characterise the pattern of protests over time seem to be mirrored in the temporary nature of the shifts in public opinion they can cause.

This raises serious questions about the efficacy of protests whose primary aim is to change public opinion, because they operate at a completely different timescale to the slow cycles of policy development, institution building and cultural growth that are needed for fundamental political change. If politicians know that people’s attention is likely to have wandered away after a few short months, they have little incentive to follow through with meaningful reforms.

|

| Add caption |

Source: Omar Wasow, “Agenda Seeding: How 1960s Black Protests Moved Elites, Public Opinion and Voting”, American Political Science Review, Volume 114, Issue 3.

The transitory nature of changes to public opinion shown in Figure One is backed up by a wider body of evidence. For example, Michael Biggs, Chris Barrie and Kenneth Andrews recently showed that the Civil Rights Movement had only negligible long-term effects on the attitudes of white Americans, making them no more likely to have liberal views on race or to support the Democratic Party. So if the effects of more ‘respectable’ protests can also be questioned, where does that leave riots?

One often-ignored aspect of rioting is its ability to produce new generations of leaders and organisers and to serve as an inspiration for future struggles. As Vicky Osterweil argues in her forthcoming book, In Defense of Looting, many significant political movements were born in moments of riotous insurgency – Stonewall being an obvious and important example. The methodological challenges of measuring and testing these long-term cultural effects are enormous, but that doesn’t mean they should be dismissed.

There’s also the question of whether riots should be thought of as a ‘tactic’ at all. They are obviously not ‘scheduled’ in the same way as a demonstration or a protest. Nor are they as easy to contain and control as a march or a public meeting. Rather than asking whether riots are ‘effective,’ maybe we should ask whether they are justifiable reactions. Expressions of grief or anger may do little to challenge or change the situation which provoked them, but they can still be seen as apt and important responses. I have some sympathy for the consequentialist logic of focussing on the efficacy of riots, but we should be open to other frameworks of evaluation too.

Finally, it’s worth asking whether the reported backlash against the riots of the late 1960s is likely to be repeated in 2020. On the one hand, both sets of riots came shortly before presidential elections. The stakes are therefore similarly high. But on the other hand, today’s very different media environment may alter the power of reporters to frame these events in positive or negative ways.

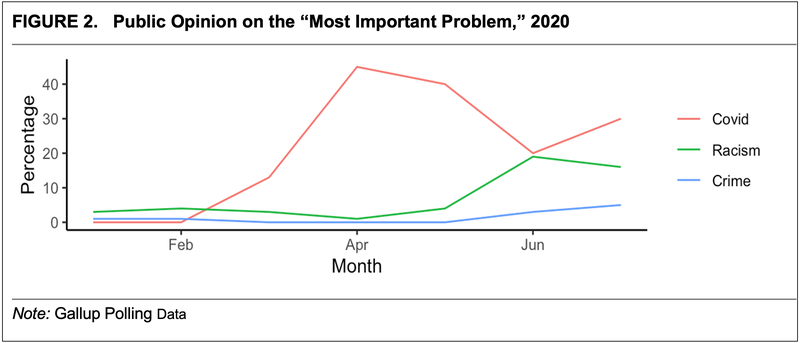

Social media, for example, has proven vital to the recent wave of protests against racism and police brutality, enabling the sharing of images and videos and serving as a vital educational and advocacy tool. So far, the impact of the protests on public opinion has been largely positive, with far more people overall citing race and racism as the most important problem facing the United States than crime and violence – though the latter has increased since May of 2020, particularly in certain demographic groups.

And while the rise in attention to racism shown in Figure Two is far smaller than the equivalent trend from the 1960s, the context of Covid-19 makes any direct comparison extremely difficult, especially when the question pollsters are asking concerns the ‘most important problem we face.’

|

| Add caption |

Source: Author’s graphic, compiled from Gallup Polling Data, 2020.

It’s also worth emphasising that the effects of any event on public opinion are only partially determined by the characteristics of the event itself. Much more significant is the political struggle to represent it in particular ways in the public imagination.

So rather than criticising riots that have already happened, our focus should be on pointing out the absurdity of a logic in which systematic murder is excused but property damage is condemned; on demonstrating the ongoing horror of racist violence; and on depicting the myriad ways in which structural oppression is reproduced. That is the fight to which we must rededicate ourselves.