A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Wednesday, September 9, 2020

As Russia faces an economic downturn, migrant workers are paying a brutal price

Over the past month, migrant workers in Russia have faced retaliatory round-ups, harassment and brutal treatment at the hands of police. This campaign follows official comments on "rising migrant crime" due to the COVID-inspired economic downturn.

|

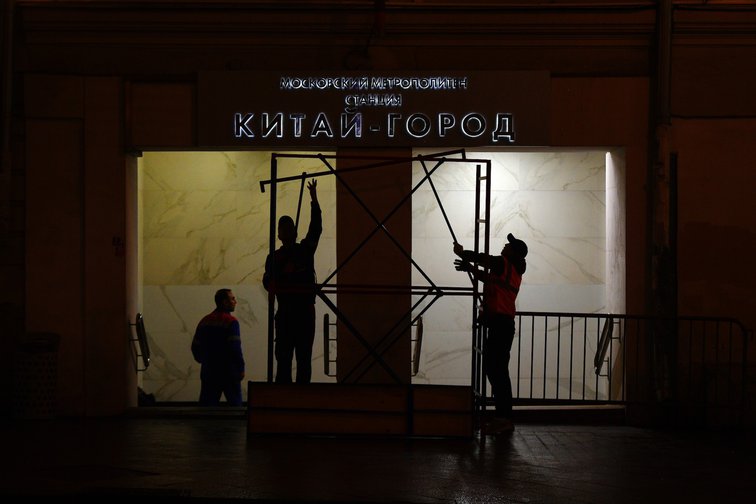

(c) Kommersant Photo Agency/SIPA USA/PA Images. All rights reserved

Damelya Aitkhozhina-9 September 2020

In Russia, diverting public frustration over domestic economic and political problems to a designated “enemy” is nothing new. In the past decade, politicians and state-friendly media have variously highlighted a revolving carousel of groups - migrants, LGBT people and critics branded as a “fifth column” - as scapegoats to shield the government from criticism over economic hardships or problems in domestic or foreign policy.

In the wake of Russia’s Covid-19 economic downturn, we’re witnessing a new spin of the carousel. This time the target is, once again, migrant workers. The sectors of Russia’s economy that employ the largest numbers of migrant workers, such as construction and hospitality, were also hit by lockdowns. Many employers had to lay people off.

New research shows that the pandemic’s economic dimension hit a majority of people in Russia hard, but that migrant workers have been hit the hardest. In April and May this year, researchers at the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration conducted a self-selecting online survey of 2,074 people - migrants born in and/or nationals of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, and locals born in Russia. The study found that 75% of surveyed migrants had been either laid off or forced into unpaid leave, and over 50% had lost all sources of income and were barely surviving. One of the key conclusions of the research was that despite fears and expectations to the contrary, criminality among migrants has not increased. Instead, researchers found, migrant communities had developed solidarity and mutual support as a collective survival strategy.

But in early August, those research findings were used to send the opposite message. Dmitry Medvedev, Russia’s former prime minister and now deputy chair of the Security Council, quoted the study’s data on migrant unemployment, speculating that it would lead to an increase in crime, even though the research found otherwise. He proposed making it harder for migrants to get work permits, referring to systems in Gulf states that Human Rights Watch has found to be extremely abusive.

It is not clear what data he was referencing to back up his claim, since the available Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs data actually show a 3.8% decrease in crimes committed by foreigners, including a 2.2% decrease by Commonwealth of Independent States nationals, in the first six months of 2020 compared with the same period last year. The ministry itself in May and June issued statements that dispel any myth about rising criminality among migrants.

Medvedev’s comments came in the midst of a series of raids, round-ups and detentions of migrants near the Tioply Stan market in Moscow. It started on 1 August, when police detained a Tajik migrant worker. There are different versions of how he came to be detained and placed in a police car, but a group of apparently Tajik migrant workers dragged him out, put him in another car, and sped off with him.

Over the next 10 days, police rounded up and detained hundreds more migrants in and around that market, most apparently from Tajikistan, seemingly in retaliation. Those detained made allegations of police brutality and extortion.

One man told me he was detained twice near the Tioply market in the space of three days. On the afternoon of 4 August, police detained him and four other Tajiks near the entrance to the Tioply Stan metro station. Police took them to the police station, checked their IDs, migration documents, and phones, and released them around 11 p.m. He was reluctant to return to the market, but as it has affordable prices and he had heard that raids had ended, he returned on 6 August. He found police surrounding market entrances and detaining people without explanation, himself included.

One man said he saw police beating people and, in several cases, smashing detainees’ heads into the side of a police bus. Later police dragged an unconscious man onto the bus where he was held and refused to call an ambulance

The man said he saw police beating people and, in several cases, smashing detainees’ heads into the side of a police bus. Later police dragged an unconscious man onto the bus where he was held and refused to call an ambulance. Among the roughly 40 people on the bus were a few Russian nationals who were ethnic Tajiks and were detained despite showing their Russian passports.

He saw two other police buses holding detainees, estimating that over 100 people were detained. They were taken to a police station. They waited in the yard in the heat without water or food for hours, while police called them in one by one, to take their details, photos, and fingerprints. He said that when he and others asked why they were detained, police scoffed and mentioned the earlier incident at the market.

Despite repeated requests, the police did not provide an interpreter and refused to contact the Tajik embassy. Some people managed to phone the embassy on their own, and diplomats called the police station. He said the diplomats told him the police repeatedly denied that the people who had contacted the embassy were in their custody. Of the dozens detained, he estimated that only five or six people were charged with migration irregularities. The rest were released without explanation several hours later.

A university student from Tajikistan who was also detained on the evening of 4 August, said that police approached him at a bus stop near the market as he was on his way to see his mother in a town about 95 kilometers away. He said that all of his migration documents were in order, but police insisted that he pay a fine, threatening to have him deported.

Frightened, he paid the fine, but was not issued a charge sheet for the supposed offense. Police also fingerprinted and photographed him and held him for about six hours, without food or water. They released him around midnight, too late to catch the bus, so he had to sleep on the street that night.

He also interpreted for two Tajik teenagers, both under 18, whom police also fined even though, as far as he could see, their documents were in order.

Valentina Chupik, a human rights lawyer who runs a hotline for migrants, told me that in early August she received calls daily about the detentions at Tioply Stan, primarily from Tajiks. She estimates that hundreds were detained that week. She received numerous reports about police brutality. Most detainees spent hours in detention, but many were released without charges.

The raids and detentions culminated on 11 August, when, according to media reports, the Russian Federal Security Service conducted a joint special operation with police and National Guard at Tioply Stan, detaining hundreds. Chupik said police questioned some of the migrants who had contacted her about how they got her number and forced them to write a statement that they had no complaints about police conduct.

Complaints about migrants in the city have topped a recent public opinion survey in Moscow, with 30% of the 508 respondents referring to migrants as a problem. The Analytical Center Levada, the independent polling agency that conducted the survey, noted that the results were a sign of growing discontent over deteriorating living standards, with people diverting their dissatisfaction with the situation to migrants. Levada drew a parallel to 2013, when the Russian economy was hard hit and anti-migrant attitudes increased.

After a fight involving police at one Moscow market in 2013, Russian authorities raided markets across the country, detaining thousands of migrants. A number of openly far-right vigilante groups sprang up, organising “raids” on migrants, some violent, and often operating with complete impunity. The police response was woefully delayed, and police even considered giving these groups a role in patrolling the markets.

As policymakers try to displace public anxiety about Russia’s economy with stoked fear of migrants, migrants pay the price. They are easy targets. They are portrayed as the “dangerous other” and lack effective protections. Advocating on their own behalf can easily result in more trouble, which none can afford. It is safer for them to be silent. So, it is important for others to speak out and stand up for them, forcefully challenging the malevolent propaganda spewed about migrants, and demanding respect for their rights and the rule of law.