A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Thursday, September 10, 2020

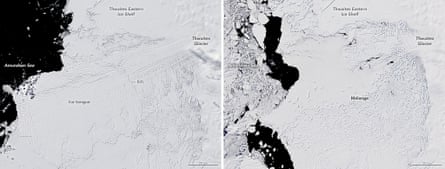

Huge cavities threaten glacier larger than Great Britain

Water seeping into fissures in Thwaites glacier in Antarctica, accelerating rise of sea levels

|

Jonathan Watts Global environment editor @jonathanwatts-Wed 9 Sep 2020

British scientists have mapped cavities half the size of the Grand Canyon that are allowing warm ocean water to erode the vast Thwaites glacier in the Antarctic, accelerating the rise of sea levels across the world.

Like decay in a tooth, the channels of warm water are melting the ice from below, threatening the stability of a glacier that is larger than Great Britain.

Using an aircraft, ship and robot submarine, the British Antarctic Survey and a US team traced the seabed terrain and the bottom of the ice shelf to measure the gaps that have opened between previously grounded sections of the glacier.

They measured two old cavities that were roughly six miles (10km) across and 800 metres deep, which allow warm water to seep under the ice. These have formed over at least 10,000 years. In addition, they mapped several new, thinner fissures that have branched off from these main trunks amid the warmer temperatures of the past 30 years.

The results were published this week in the Cryosphere journal. The good news is the new channels are not yet as large as had previously been assumed, which suggests the collapse of Thwaites may not come as soon as feared. The bad news is scientists believe the cavities are widening but they do not know how fast.

“Before we did these studies, the assumption was that all the channels are the same, but the new ones are much thinner and more dynamic. They will get bigger over time,” said one of the lead authors, Tom Jordan, an aerogeophysicist at the British Antarctic Survey.

“Understanding that process and how these cavities evolve will be key to understanding how Thwaites and western Antarctica will change in the future.”

|

That is one of the most important questions in the world today. The paper notes that Thwaites glacier covers 74,000 sq miles (192,000 sq km), and is particularly susceptible to climate change.

Over the past 30 years, ice loss from Thwaites and its neighbouring glaciers has increased more than fivefold, accounting for more than 4% of global sea-level rise. If the glacier collapses completely, it would add another 25in (65cm). Many scientists believe this process is already under way but the speed of collapse remains unknown.

The new study is part of an attempt to assess those risks by the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration.

“We are only halfway through the process so these are interim statistics,” Jordan said. “Intuitively, it would seem that the new thin cavities will let in less warm water so the collapse of the glacier would be slower than previously believed, but that needs to be confirmed. This data should be included in future models.”

There have been some discussions about geoengineering to block the flow of warm water, but Jordan said this would be expensive in such a remote region. Instead, he called for a reduction in emissions as the most cost-effective way of easing climate impacts.

“Theoretically, we could build a dam to stop the hot water coming in. But these channels are ridiculously large. We can intervene more cheaply by reducing carbon dioxide,” he said.