A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Tuesday, December 22, 2020

To avoid descent into barbarism, Russia needs real socialism

What does a post-Putin and post-neoliberal future look like in Russia?

|

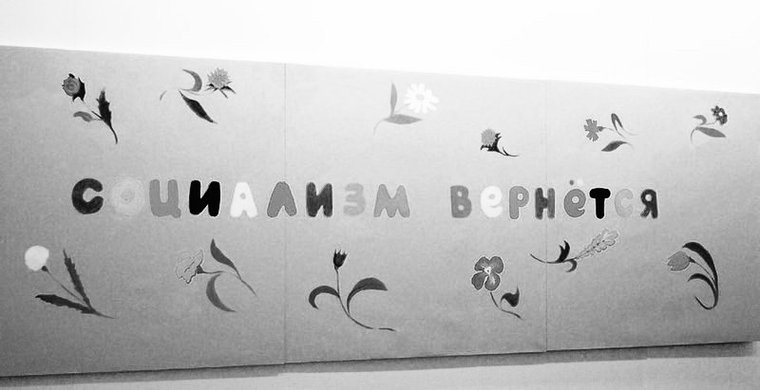

"Socialism will come back"| Flickr. Some rights reserved

Kirill Kobrin-21 December 2020

This year, Russia held a constitutional referendum - a strange, even superfluous exercise in a country fighting coronavirus - but one that has become a landmark in the country’s political and ideological history. Putin’s regime, carefully constructed over the past 20 years, has reached its apex of power and control. But having reached Putinism’s peak, it’s clear that the system has found itself at a point of no return - socially, economically and ideologically.

What comes after this? What does a post-Putin and post-neoliberal future look like in Russia? This series of three articles by writer Kirill Kobrin - published this week - will trace the outline and problems of this future. This series is neither an exercise in futurology, nor an “expert risk analysis”, but rather an attempt to hint at the possibilities of this new, coming environment.

2. Russia’s liberal intelligentsia and the post-Putin consensus

3. Sliding into isolation: Russia and the world

In 1916, Rosa Luxemburg published The Junius Pamphlet (aka The Crisis of German Social Democracy), which contains, among other things, the following passage: “Friedrich Engels once said: ‘Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads, either transition to socialism or regression into barbarism.’” Although Luxemburg attributed this striking assertion to Friedrich Engels, it was written by the German socialist Karl Kautsky. However, earlier than Kautsky, Engels had noted that without progress towards socialism, capitalism would plunge the world into real barbarism. Engels cited major conflicts as one of his examples.

Some 40 years later, universal barbarism did erupt, first from 1914 to 1918, and then from 1939 to 1945. However, before the First World War, and between it and the Second World War, and after the Second, there was also a surplus of barbarism – ranging from the real genocide orchestrated by the Belgians in colonial Congo, to systemic racial discrimination in the United States and apartheid in South Africa. You can argue with the term “barbarism”, which, in the progressive times of Engels, meant everything that had happened between antiquity and the bourgeois era (that is, the Middle Ages). Leaving aside the historical context, however, Engels, Kautsky and Luxemburg were at least partly right.

The Soviet Union itself was no laggard when it came to barbarism. I will not recite all of its crimes: suffice it to recall the Gulag and the mass deportations of whole ethnic groups. But here again there is a matter of terminology, and a much more serious one. What is “socialism”? Is Soviet socialism (or Chinese, or North Korean or Cambodian, and right down the list to the mildest species of socialism, Yugoslavian) the only socialism or even the principal form of socialism?

We know the answer: no, it is not. There is a European social democratic model: even if it is in crisis today, it is still quite effective. The coronavirus crisis of 2020 has demonstrated the welfare state’s resilience: we need only compare the situation in some Scandinavian countries and especially in Germany to the near-total disaster occurring in the US and the UK. The latter has coped with the pandemic despite its shambolic right-wing government and only thanks to the socialist system of free medical care introduced 70 years ago.

The slogan “socialism or barbarism” gave rise to the well-known eponymous European leftist group, which existed from 1948 to 1967 and was aligned with the Situationists. The slogan also had an impact on the so-called revolution of 1968. Finally, in 2001, it served as the title of a book by the Hungarian-British post-Marxist István Mészáros, in which the US was identified as the field of the decisive battle for socialism and against barbarism. As we can see, nothing like this has been observed in America in the last 20 years, rather the opposite. Below, I shall argue that something similar could happen in Russia.

The use value of Soviet socialism

Russian society’s attitude to socialism is twofold. On the one hand, the further the Soviet era recedes into the past, the stronger the nostalgia for it. Sociologists and other impartial observers have noted that such nostalgia is common among people who could not have known about the existence of Brezhnev or Chernenko, even from popular anecdotes of the 1970s and 1980s, because they were born later, grew up in post-Soviet Russia, and have experienced the Soviet period’s charms only in Soviet movies and discussions on social networks.

Two things are worth noting here. Firstly, this nostalgia for socialism is often absolutely material, that is, bourgeois in essence: it is focused on things, such as “real sausage without preservatives”, Alyonka chocolate bars, and "Soviet champagne". It is a brand sentimentalism that meshes perfectly with neoliberal consumerism.

Consumeristic nostalgia for the Soviet Union is challenged by those who point to the real experience of material life under Soviet socialism. A shortage of goods, long queues at shops, and the unavailability of everything that constitutes today’s material environment make up the reality of the “truth about socialism”. Life in the USSR was impoverished, inconvenient (especially from today’s point of view) and miserable. Ultimately, as recently noted by a former classmate of Roscosmos chief Dmitry Rogozin (who had suffered yet another bout of sweet longing for his great homeland) it was barbaric. (Just recall the fetid hell of Soviet public toilets). Socialism is barbarism, and material barbarism at that. So, despite all the troubles caused by Vladimir Putin’s authoritarian regime, the present is better. There is no turning back from capitalism to socialism – meaning, from capitalism to barbarism.

Despite all the seemingly powerful Soviet nostalgia, socialism – the idea and practice of social justice – is not on the political agenda in Russia

Hence, despite all the seemingly powerful Soviet nostalgia, socialism – the idea and practice of social justice – is not on the political agenda in Russia. None of the country’s formally registered and institutionalised political parties (the real ones, the fake ones, the fronts, the vanity parties) mention social justice in their programmes. They only mention the “wellbeing” of citizens, with no consideration of their class status, social origin or regional affiliation. In other words, Russia’s current socio-political structure – neoliberalism, in its corrupt state capitalism format – is not questioned.

This arrangement is presented as natural, as a kind of (second) nature that requires the right tweaks and improvements, nothing more. The same stance has been adopted by the most active and influential segment of the opposition, from Moscow’s professional liberals to the populist Alexey Navalny. Neoliberalism and state capitalism should be regulated and rid of corruption (especially the alleged main source of it: Putin and his entourage), but they should be left intact. This is the unspoken but actual political programme that unites the Russian opposition today. And on this point, the opposition concurs with its principal enemy, the very regime it is fighting.

The main issue on the Russian agenda, then, is inevitably neither social nor socio-economic, but political – namely, democracy. The Russian authorities are anti-democratic: something they themselves would grudgingly admit, explaining the dismantling of democratic institutions and procedures (which had barely emerged after the collapse of the USSR) either in terms of the need to mobilise against “external enemies”, or (and this is the more interesting argument) because of a general consensus in support of Putin and his system. This “consensus” is, again, presented as natural, as a matter of fact (an impression facilitated by the almost complete state control over polling organisations and opinion polls) and, most importantly, coming from the people themselves.

“The people” (narod), as a group in and of itself, is presented as something whole, organic, ontological - not divided into classes and social groups - and so “democracy” is, naturally, the “will of the people”. In turn, the opposition (the broadest spectrum of dissatisfied people) criticises the regime for destroying democracy and its procedures and institutions – in particular, elections. Democracy is conceived as a non-historical condition, as a universal system invented “in the West” that forms the basis of the so-called first world’s prosperity. Once democracy has been established (or rather “restored”) everything will be fine – socially and economically. The will of the electorate (the self-same indiscernible “people”) must be expressed through long-established procedures; the power established this way will be just. Having been shown the door, the question of social justice, of socialism as the basis of society, crawls back in through the window.

|

However attractive, this position is vulnerable, and, in present conditions, doomed to failure. Democracy in its current form is going through a profound crisis. Democratic elections have brought right-wing populists – that is, enemies of real democracy – to power in the US, Poland, Hungary and the UK. Technological progress via the internet and social media has made possible the cynical manipulation of public opinion, fatally affecting the choices made by citizens at the polls. Classical (Western) democratic institutions have revealed their direct dependence on political and economic elites, who have even stopped concealing this dependence.

Finally, the illusory link between “democracy” and economic prosperity and progress has become apparent, as illustrated by such undemocratic and simultaneously rapidly developing countries as China and Singapore, for example. In other words, democracy, which the Russian opposition has been fighting for (especially in Moscow), does not solve any real problems, improve standards of living, or ensure social justice. On the contrary, it is an effective weapon in the hands of the ruling classes. There is no “democracy or barbarism” dilemma. President Donald Trump, who earlier this year suggested that people ingest household chemicals to ward off the coronavirus, was elected by people living in the world’s main democratic power.

Democracy first!

Nevertheless, socialism and democracy (albeit veiled and transformed) are objectively two of the most important topics on the political agenda in Russia today.

Let us start with democracy. In this case, Russia’s point of no return was this past summer’s referendum on amendments to the constitution, which cancelled democracy in Russia on a purely rhetorical, propagandistic level. The indifference with which procedures for expressing the popular will were violated, the blatant use of voting to change Russia’s basic law in order to maintain the power of a handful of billionaires, and the refusal to give a coherent explanation for the need to hold a referendum in the midst of a pandemic (thus endangering the health and lives of citizens) put an end to all talk of “democratising the system”. The silver lining is that a different conversation about a different kind of democracy has already begun – on Russia’s streets.

The massive demonstrations that kicked off in July in Khabarovsk, in which tens of thousands of people protested the removal and arrest of the region’s popularly elected governor, have confused many observers. It is hardly possible to describe most of the protesters as “supporters of democracy” to which Russia’s “democratic opposition” appeals. Governor Sergey Furgal, whose arrest on murder charges sparked the protests, has been a leading member of Russia’s Liberal Democratic Party, a party that makes United Russia look like a club of well-meaning liberals. Furgal was a member of the State Duma in the nine key years in the country’s history when, aided and abetted by parliament, the Kremlin finally turned Russia into an autocracy at home and an aggressor abroad.

It seems that the business that Furgal pursued in Khabarovsk before his election cannot be objectively classified as squeaky clean (which, of course, does not automatically mean that he was involved in the crimes of which the Kremlin now accuses him). In other words, he is less than a perfect fit for the role of heroic martyr of Russian democracy. Nevertheless, the protests in Khabarovsk have been purely democratic in nature – not because of the person for whom residents stood up, but because of what he represents to them. In fact, the people of Khabarovsk are protesting the lack of democracy in their region.

|

Khabarovsk, in Russia’s Far East, is one of the few regions in the country that can still elect its own leader. Furgal’s victory was an extremely rare occurrence: a candidate who was not backed by the Kremlin won what were imagined to be rigged elections. Residents voted for Furgal, but this outcome was cruelly and unceremoniously derided without warning. That is, they are not offended because they were “not heard”. They are outraged because the powers that be simply do not want to listen to them. Since the very possibility of being heard has vanished, the theoretical possibility of declaring one’s existence has also disappeared, and this was what humiliated people in Khabarovsk the most. The same thing happened (on a smaller scale and for different reasons) in Yekaterinburg in 2019. Regardless of local differences and agendas, in both Khabarovsk and Yekaterinburg what is and was at stake is the inability to express your opinion, be heard, and show that you exist. And that is a genuine matter for democracy.