A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Saturday, April 17, 2021

The remnants of Golden Dawn are winning support in Cyprus

The neo-Nazi group might be in prison in Greece, but in Cyprus their local offshoot is getting ready for elections. How will they do?

|

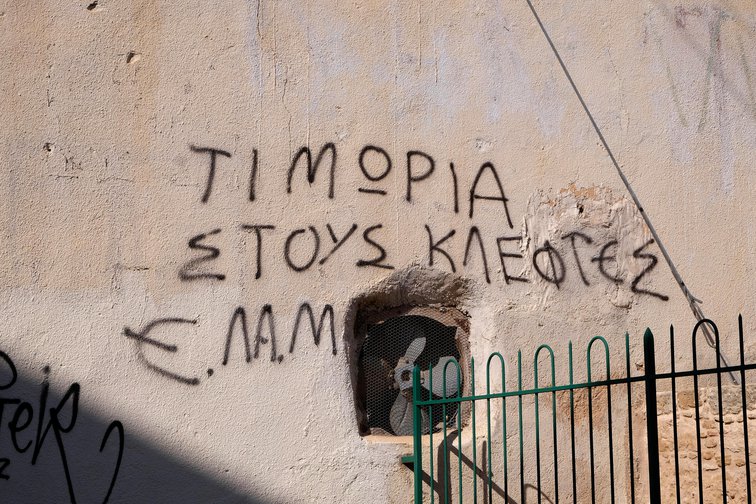

'Punishment for thieves ELAM'. ELAM is an ultra-nationalist, far-Right, anti immigration party | Hugh Olliff / Alamy Stock Photo. All rights reserved

With former MPs and members of the Greek neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn currently behind bars, it is easy to forget that the group’s offshoot in Cyprus has been growing steadily for the past ten years.

The ultra-nationalist, far-Right National Popular Front (Ethniko Laiko Metopo, ELAM) was founded in 2008 by Christos Christou, who served for many years at the side of Nicos Michaloliakos, the now imprisoned head of Golden Dawn. Now, with parliamentary elections scheduled for May, a large question mark looms over the future of the extreme Right in Cyprus. With the island mired in an ongoing pandemic, accusations of government corruption and protracted divisions between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, how will ELAM fare?

ELAM officially registered as a political party in 2011, after it had unsuccessfully attempted to be recognised as ‘Golden Dawn, Cyprus Branch’ in 2008. Initially, ELAM flew under the radar and was only known for its members’ violent street attacks against migrants and minorities.

After the controversial Eurogroup bailout deal for Cyprus’s banks in 2013 and a period of austerity measures, ELAM saw its ratings rise. From winning 0.88% of the vote in 2013, it reached 2.69% in the 2014 European Parliament elections and in 2016, with 3.71%, finally succeeded in sending two MPs to the Cyprus parliament.

The most recent presidential elections, in 2018, continued the steady increase in ELAM’s appeal. Its leader Christos Christou won 5.65% of the vote, which was the fourth highest share (though significantly below the first three contenders). Part of the reason for this success was the party’s targeted charity campaigns in a context of increasing poverty and dissatisfaction with European politics. Donations of food and clothing followed the Golden Dawn model by helping Greeks only and blaming migrants for the country’s socio-economic decline. But where does ELAM stand today, a year after the onset of the coronavirus pandemic?

ELAM has managed to dissociate itself from the neo-Nazi symbolism of Golden Dawn

In January, using the message Cyprus First and photos from a stock image library, ELAM launched a Facebook page that cheekily circumvents their ban from the site and presents a completely mainstream version of the party’s platform. ELAM lost its access to Facebook in 2019, a few months after a similar ban was imposed on Golden Dawn.

Indeed, it is remarkable how a party whose followers initially kept their membership a secret is now attracting a wide range of well-educated and connected candidates, certainly compared to previous candidates. Among them is Demetris Souglis, a well-known journalist, and Andreas Themistokleous, a former MEP who was once censured by his European Union colleagues for his homophobic rhetoric.

Furthermore, unlike their ideological siblings in Greece, ELAM has managed to dissociate itself from the neo-Nazi symbolism and especially the violent outbursts that had become the trademark of Golden Dawn. But Christou has not been shy about reminding people of ELAM’s potential for violence.

In 2019, after his speech presenting ELAM’s MEP candidates, Christou was asked why he had not completed the military service that is obligatory for men in Cyprus. He explained that it was due to health reasons, then added: “When they decide again to judge ELAM in terms of its military service, they should be very careful because we may choose to respond in a military way and implement an unorthodox political war.”

Pandemic response and anti-corruption

ELAM has used the COVID-19 pandemic to advance its xenophobic agenda. The party’s initial reaction to the imminent arrival of the virus in February 2020 was similar to that of Matteo Salvini in Italy and Viktor Orbán in Hungary, both of whom focused on closing borders and fending off “illegal” immigration as the solution to the spread of COVID.

When the Cyprus government shut the UN-controlled ‘Green Line’ checkpoints that separate Greek Cypriots in the south and Turkish Cypriots in the north – before it had even started to take serious measures at the airports – ELAM was the loudest voice pushing for these restrictions.

And when the country began to slowly open up again, in May 2020, ELAM insisted that the Green Line should remain closed – until there is a solution to the Cyprus problem.

In many ways, ELAM’s response to the pandemic is similar to that of other far-Right parties in Europe. As Jakub Wondreys and Cas Mudde argue, apart from the flamboyant examples of Bolsonaro in Brazil and Trump in the USA, most far-Right parties supported extreme lockdown measures, because these provisions served their larger goal of border control.

In October 2020, Al-Jazeera dropped ‘The Cyprus Papers’, an explosive video of investigative journalism that traces government officials’ corruption in the so-called Cyprus Investment Program. This initiative allowed foreign nationals (specifically non-EU citizens) to apply for a Cyprus passport alongside proof of their intention to invest a few million euros in real estate ventures. It was one of the measures taken by the country’s cash-strapped government after the 2013 Eurogroup decision.

Al-Jazeera’s undercover team shows lawyers, MPs and the Speaker of the Parliament playing along with a sketchy plan to sanitise a fictional applicant’s criminal past in order to get his application approved.

This gave ELAM an easy opportunity to score points. To remind everyone that they are “clean” (much as Nicos Michaloliakos talked about “the clean hands of Golden Dawn”) and that “the people” can no longer tolerate corruption and dishonesty. With the president and his ruling centre-right Democratic Rally party (Democratikos Synagermos, DISY) mired in corruption scandals over the ‘Golden Passports’ debacle and the recent handling of the pandemic, a message of decency goes a long way.

But ELAM is facing rivals in its anti-corruption campaign: an array of post-pandemic groups and political parties that cover all bases, including anti-vaxxers, “Awaken Cypriots,” those who watched their deposits evaporate in the 2013 Eurogroup banks bailout and even active QAnon followers.

Having lost the lifeline of Golden Dawn support, it is unclear how ELAM can maintain its monopoly as the alternative party, fighting for “the people” and for the type of solution to the Cyprus problem that involves a lot of magical thinking.