A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Monday, August 2, 2021

The colonial idea that built the Palestinian Authority

Israel tried for years to create a body that would control Palestinians on its behalf. It was the liberation movement's leaders that helped it succeed.

|

(L to R) Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat, U.S. President Bill Clinton, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, and Jordanian King Hussein bin Talal at the White House after signing the Oslo II Agreements, Sept. 28, 1995. (Avi Ohayon/GPO)

The horrific killing of the activist and outspoken critic Nizar Banat at the hands of Palestinian Authority security forces, and the subsequent brutal crackdown and arbitrary arrests of Palestinian protesters, activists, and journalists, have widened the debate among Palestinians about the PA’s place within Israel’s occupation regime.

What makes the latest debate particularly significant is that it has attracted a considerable segment of apolitical and depoliticized Palestinians. Illusionary slogans of “state-building” are being blatantly rejected by more and more Palestinians. On social media and in public discussions, it has become common to label the PA as “collaborators” and its security forces as the “guardian of Israeli settlements,” while ridiculing the success of the “national project” depicted by PA apologists. Perhaps most strikingly, much of the Palestinian public today openly perceives the PA as an extension of Israeli colonial rule that is incapable of advancing their struggle. And they are correct.

Established in 1994 under the Oslo Accords as an inter-elite accommodation between the Palestine Liberation Organization, Israel, and the latter’s Western partners, the PA effectively traded the Palestinian liberation struggle for a limited form of self-rule that is completely besieged by and dependent on Israel in almost every sphere.

The PA not only imposed structural constraints on Palestinians to resist Israeli policies, but actively collaborated with Israel in a way that served the latter’s myriad security, economic, and political interests. The advent of the PA further led to the demise of the PLO, which ended the leadership’s representation of the Palestinian diaspora outside the Oslo-created cantons, and ultimately subordinated and coopted the Palestinian national movement.

|

Palestinians protest the death of Palestinian human rights activist Nizar Banat who died after being arrested by Palestinian Authority security forces, in the West Bank city of Ramallah, on June 24, 2021. (Flash90)

This historical trajectory intersects perfectly with Israel’s logic of colonial governance. For over a century, the Zionist movement has pursued a doctrine of “maximum land with minimum Arabs,” seeking to neutralize the Palestinian “demographic burden” that impedes Jewish sovereignty over the land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea.

However, given its inability to reiterate a similar campaign of large-scale ethnic cleansing like in 1948 — due to both local resistance as well as regional and international pressures — Israel has instead embarked on multifaceted strategies of population management and control to keep the territorial-demographic equation in favor of the settler-colonial project. After the 1967 occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, the priority became to ensure that Israel could continue colonizing the land while excluding the Palestinians from power and concentrating them into tiny slots of territory.

A fundamental pillar of this logic was the creation of a “native” institution charged with controlling Palestinians in densely populated areas. This idea derived from many historical precedents from Africa to Southeast Asia, where colonial powers routinely invented and cultivated local authorities to sustain their rule.

These authorities were often put into the hands of traditional elites who, with the power’s patronage, served to mediate between the colonizer and colonized, enforce security and stability, and reduce the costs of colonial bureaucracy and military operations. They also developed local police or militia forces to ensure public order, protect the elite from internal opposition, and suppress any form of resistance. When national liberation movements later emerged to overthrow their rulers, these local authorities were viewed as collaborationist entities and were resisted and dismantled as such.

The autonomy formula

Israel has long tried to implement this colonial logic by encouraging a vision of “Palestinian autonomy” under its rule. In the immediate aftermath of the 1967 war, for example, Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan spearheaded the “Open Bridges” policy, a counterinsurgency strategy that encouraged local leaderships such as heads of tribes to manage their own communities’ affairs, as a way to pacify the Palestinian population.

|

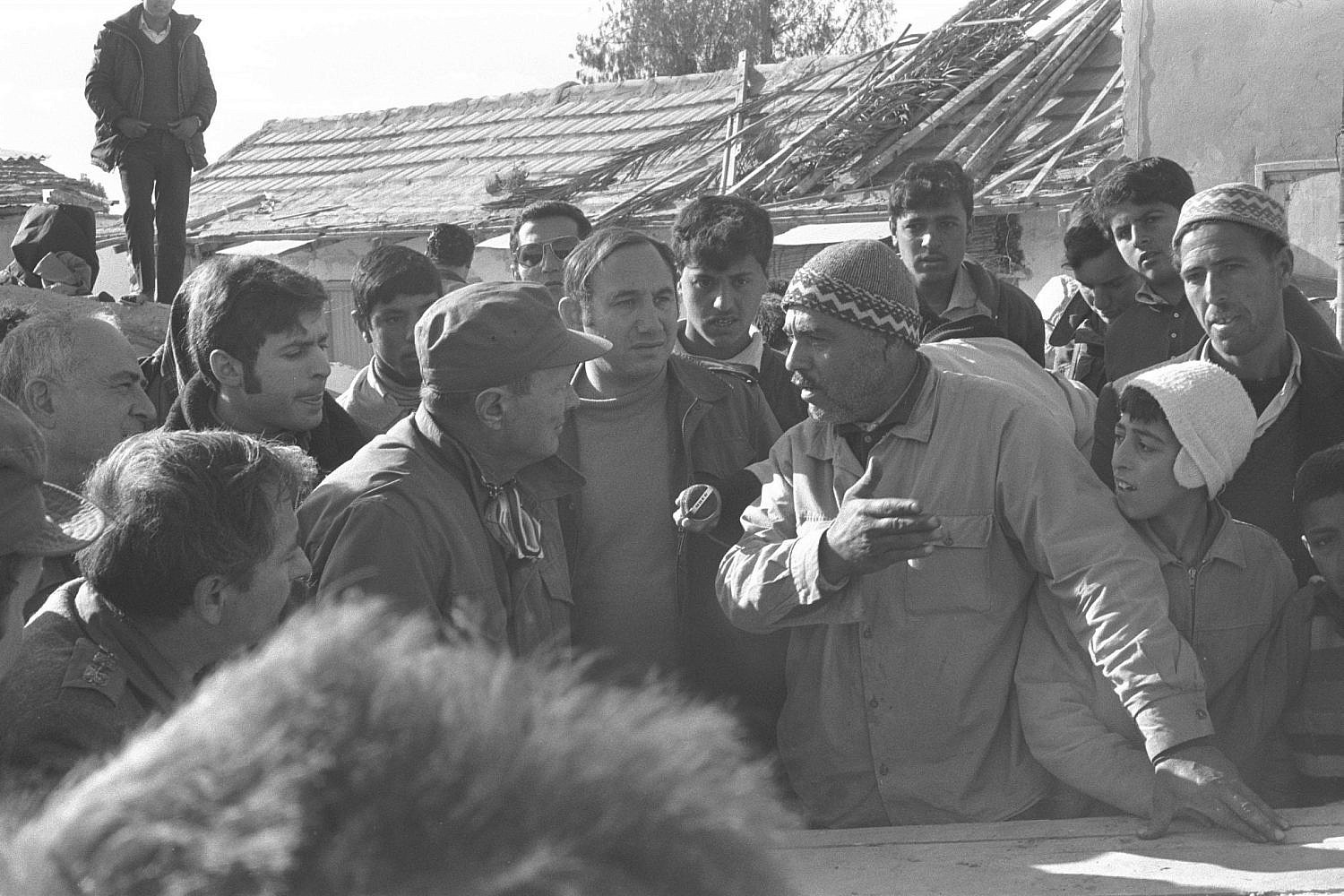

Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan (l) speaks with a Palestinian Arab resident of the Rafah refugee camp in the Gaza Strip during a visit to the camp, Dec. 28, 1972. (Nissim Gabai/GPO)

In parallel, Israel informally embraced the “Allon Plan,” proposed by then-Labor Education Minister Yigal Allon, which envisaged the “Jordanian Option” for governing the occupied territories — granting some form of autonomy in populous West Bank areas under Jordan’s auspices, while keeping the land under Israeli military control.

The most systematic model of Palestinian autonomy was presented by Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin at the 1978 Camp David talks between Israel and Egypt. Begin’s proposal was based on instituting a “self-governing administrative council,” to be administered by 11 Palestinian members, which would oversee civil affairs without holding real political power. While the Israeli military would maintain security and hold on to strategic territory, the administrative council would be able to deploy a local police force within Palestinian population centers in coordination with Israel.

To put the autonomy vision into practice, Israel formed the “Village Leagues” in 1979, a network of collaborationist tribal elders who exercised coercive policies over their own population under the direction of the Israeli military (Ariel Sharon, who served as Begin’s Defense Minister in the early 1980s, was a leading proponent of this policy). The Israeli government also hoped that the Village Leagues would undermine the PLO’s nationalist appeal in the occupied territories and splinter any attempts to mobilize the people against Israeli rule. This policy, however, was largely rejected and delegitimized by the Palestinian public, leading to its demise by the eruption of the First Intifada in 1987.

It was only with the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993 that Israel was finally able to accommodate its ambition. But while the PA is certainly a modern replica of this colonial formula, it has a peculiar feature in that it was in fact accepted by the national liberation movement itself.

|

Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres meeting with PA President Yasser Arafat in the Gaza Strip, Sept. 26, 2001 (Avi Ohayon/GPO)

The PLO’s acquiescence to this arrangement was partly driven by a self-serving agenda: the First Intifada, which had produced new forms of national and grassroots leadership inside the occupied territories, had gradually begun to marginalize the PLO leadership in exile. Threatened by this challenge, the PLO sought to reinstate its hegemonic position by capitalizing on the uprising and secretly negotiating a peace settlement with Israel, with the support of the United States.

Such a conscious encounter between a national liberation movement and a colonial power is unprecedented in the history of anti-colonial struggles. The result has been disastrous on the Palestinian national fabric, depriving it of the capacity to resist Israeli policies, while granting the state a comfortable position from which to intensify the colonization of the occupied territories.

Antithetical to liberation

Despite the façade of self-rule under the rubric of a “peace process,” the creation of the PA was essentially intended as a security project, whose doctrine is to deal with Israeli forces not as an occupier, but as a partner in a shared regime. Almost all of the PA’s institutions, including its modes of governance and its economic policies, are specifically designed to play a counterinsurgency function to pacify Palestinians — a central task of local authorities operating under colonial rule.

Security coordination is the most infamous evidence of the harmonic interaction between the PA and Israel, whereby both parties exchange information on the local population and arrest or kill Palestinians, whether political dissidents or armed militants. Although security coordination was an Israeli condition to maintain the PA’s survival, it has also become a priority for the PA to counter growing internal opposition.

|

Palestinian security forces guard a checkpoint at the entrance to the West Bank city of Hebron, Dec. 10, 2020. (Wisam Hashlamoun/Flash90)

The most prominent cases of this mutual partnership are the killings of the Palestinian activists Basel Al-Araj and Nizar Banat: whereas Al-Araj was killed by Israeli soldiers in the heart of the PA-controlled Ramallah after being released from PA prison, Banat was killed by PA forces in an Israeli-controlled area of Hebron.

A distinct feature of the PA that differentiates it from past models lies in the extensive technical and financial investment by Western donors — perhaps the most effective model of post-colonial intervention in our age. The United States and European Union helped to establish, train, and equip the security forces to focus on internal security; that is, to forcefully prevent any form of organized and effective Palestinian resistance.

To this day, the Palestinian security sector, funded by foreign governments, holds the lion’s share of the PA’s financial and human resources: it employs almost half of all PA servants and consumes around 29 to 34 percent of the budget — exceeding vital sectors such as education, health, and agriculture combined.

These international architects perfectly understood that ensuring PA compliance with Israel unavoidably requires both corruption to financially incentivize the PA elite, and authoritarian rule to protect them from public opposition. The PA elite and its cronies saw in this reality a lucrative industry: foreign aid, Israeli-granted privileges, monopolies over resources, involvement in private businesses, and embezzlement of public funds became major sources of personal enrichment. Major donors like the European Union and the United States did not act against this rampant corruption or human rights abuses so long as it was capable of maintaining security collaboration with Israel.

|

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas stands near the guard of honor outside his office in the West Bank city of Ramallah, Jan. 12, 2010. (Issam Rimawi/Flash90)

The PA’s institutional stability is further secured through the engagement of Fatah party constituents in patronage networks to ensure their loyalties and to coopt dissidents. Employment in the PA public and security sectors is highly politicized, dominated by the party members whose purpose is to extend the life of the PA despite its obedience to Israel’s oppressive conditions — even if it required them to become thugs assaulting protesters, as documented in recent demonstrations. Civil servants who voiced criticism of PA policies, meanwhile, would be immediately fired or forced into early retirement.

In this unfortunate reality, it is no wonder why many Palestinians today believe that the PA is antithetical to their liberation struggle. The PA’s capitulation and self-defeat under Oslo’s humiliating terms has had far-reaching consequences on all aspects of Palestinian life, and has inflicted countless harms on the Palestinian cause. It has introduced deep political and social divisions into the national fabric, decayed the Palestinian national movement, and weakened the international power of the Palestinian voice for freedom and dignity.

The uncritical embracement of this path is not a political miscalculation, but a systematic choice by the elites and their patrons to preserve the colonial order. As such, the PA cannot be reformed nor can it be changed; it was precisely created to function this way. Either the Palestinians take the lead and break with this path, or they risk an even worse trajectory in the not-too-distant future.