A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Monday, February 28, 2022

Inflation Talk Belies Deeper Question: Why Was Everything So Cheap Before?

A shopper places items in a cart at a home improvement store in Bethesda, Maryland, on February 17, 2022.

BY JP Sottile, -February 26, 2022

Inflation has reached a 40-year high, propelled by the pandemic’s labor and supply chain disruptions, billions in stimulus money and corporate profiteering. In response, politicians and the Federal Reserve are scrambling to figure out how to staunch the rapid rise in consumer prices. And while many obsess on assigning blame, few, if any, are asking the more trenchant question: “Why was everything so damn cheap in the first place?”

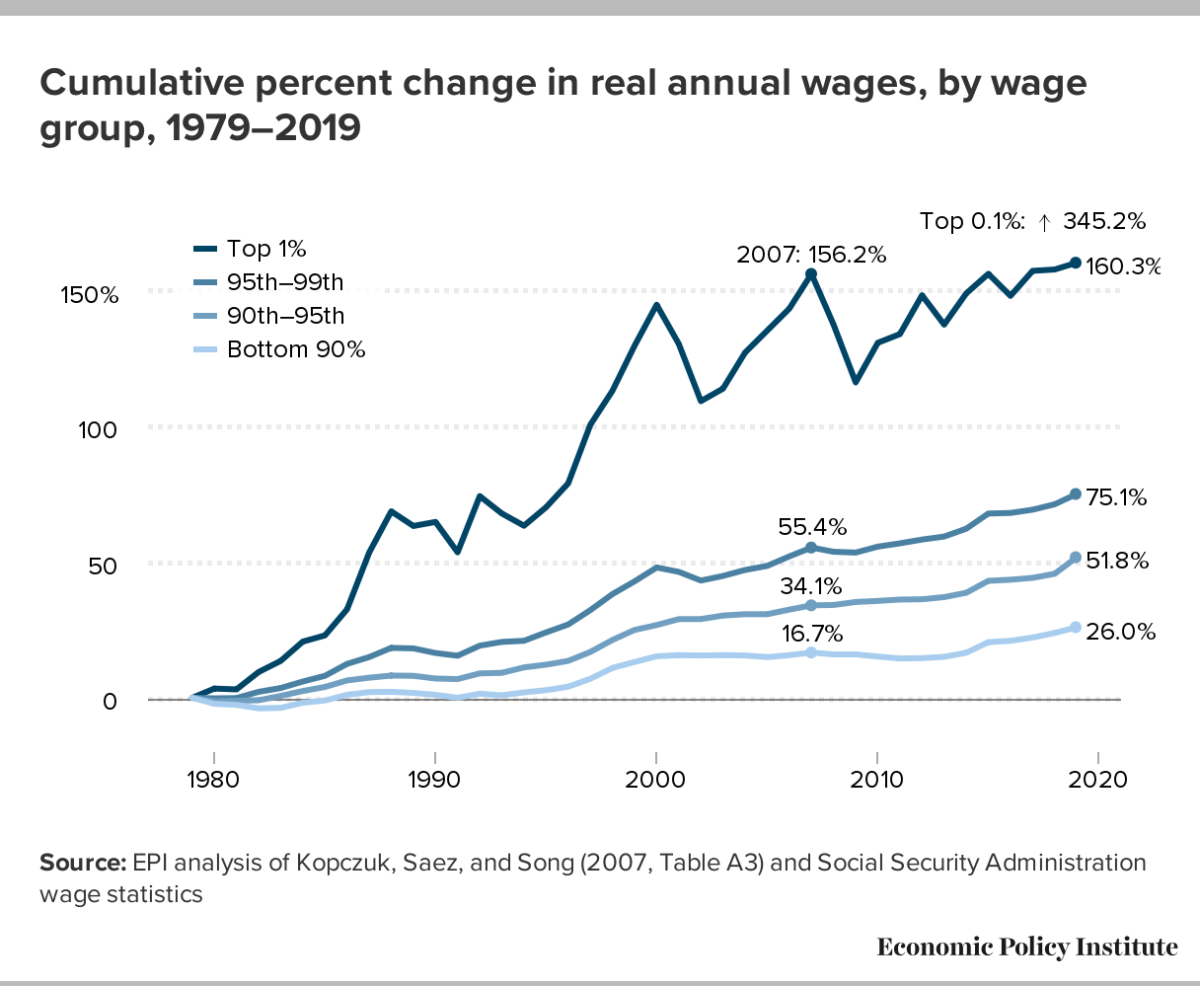

Why have televisions and smartphones and clothing and meat remained so inexpensive for as long as they have? How did corporations profit so obscenely off these ever-cheaper products? And how was it even possible for consumers to gobble up goods from a virtually bottomless pit of plenty when wealth has systematically accumulated in fewer and fewer hands since the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980?

Devotees of Milton Friedman will argue that the pit of plenty is an organic outgrowth of an increasingly unfettered and, therefore, increasingly “free” market. The truth is far more complicated. Although the neoliberal project since 1980 has ostensibly been about “free trade” and “free markets,” the U.S. taxpayer has, however unwittingly, directly and indirectly subsidized this consumption-driven system of resource extraction and labor exploitation through a vast infrastructure of defense spending, and through generous handouts to the energy and agricultural industries.

At the same time, presidents and policy makers chummed the world’s waters for corporate executives who fed like sharks in far-flung pools of low-cost labor and resources. They exploited lax and non-existent regulatory environments as they offshored jobs and pollution to build the profitable supply chains consumers now bemoan as broken.

Predictably, the mainstream media fixated on these broken supply chains when the bottomless pit of plenty suddenly and shockingly dried up. Empty shelves make for click-bait articles, and understandably so. Yet, few, if any, questioned a globe-spanning system that affords U.S. consumers the unprecedented opportunity to live a disposable lifestyle based on cheap oil, cheap labor and cheap food. This, in turn, depends on quantity over quality. Profit margins depend upon driving down costs and avoiding nettlesome labor and environmental standards. And it all depends upon offsetting stagnant wages, growing inequality and massive consumer debt with the unsustainable promise of more and more for less and less at ever-faster speeds.

As such, the empty shelves say more about the tenuous nature of the U.S.’s voracious “Empire of Consumption” than they do about the market’s verdict on stimulus checks. The pandemic — with its sudden disruptions to overseas suppliers and its brutal impact on low-wage laborers (many of whom were categorized as “essential workers” and forced to expose themselves to a risk of illness) — has, in effect, pulled back the curtain and exposed the imperial wizard pulling on supply chains that allow less than 5 percent of the world’s population to consume 25 percent of its resources.

Fistfight at the Golden Corral

On a recent Friday night in Bensalem, Pennsylvania, diners grazing on the buffet at their local Golden Corral began wielding furniture like weapons, all because of an “alleged steak shortage.” At least, that’s what many news outlets trumpeted with their click-bait headlines. However, a spokesperson for the company assured The Washington Post that the restaurant in question “never ran out of meat,” which is incredibly on-brand. In fact, endless meat is not just the essence of Golden Corral’s brand, but also the essence of the Empire of Consumption. Both are inexorably rooted in the illusion of endless plenty at bargain prices. And those bargain prices, like the growth of fast food over the last 30 years, have been built upon the backs of cheap immigrant labor.

Not coincidentally, that deep pool of cheap labor was filled by one of the great neoliberal achievements of the last 40 years — the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The “agreement formerly known as NAFTA” was nominally altered in 2020, but the damage was done. In 2017, the Department of Agriculture found that Mexico lost 900,000 farm jobs in the decade after then-President Bill Clinton (who essentially completed the Reagan Revolution’s neoliberal project) finally got NAFTA enacted in 1993.

A main cause of that not-so-great displacement was a flood of heavily subsidized U.S.-grown corn. It decimated small and subsistence corn farmers in Mexico. As Alejandro Portes of the Social Science Research Council wrote back in 2006, “The response of peasants and workers thus displaced has been clear and consistent: [T]hey have headed north in ever greater absolute numbers.”

Suddenly set adrift in a newly “globalized” market dominated by U.S. agribusiness, which also began gobbling up American family farms throughout the “farm crisis” of the 1980s, Mexican farmers fled north to work for the very “Big Ag” titans who dislodged them in the first place. These repeatedly scapegoated immigrants flocked to the burgeoning “factory farms” that filled American bellies with brutally raised industrialized meat. The factory farming model depends upon concentrated animal feeding operations, or “CAFOs,” which further decimated small U.S. family farms throughout the ‘90s.

The growth and profitability of this industrialized farming model relied on absorbing family farms at home and pulling in cheap labor from abroad. Disempowered and dependent upon the whims of their employers, undocumented workers in particular have little choice but to be compliant, despite the risk of death, dismemberment and abuse. The looming threat of deportation exploits many migrant workers for a faster and faster food system that eschews anything other than profit. It’s not coincidental that cheap, meat-dependent fast food went from an occasional treat to a daily staple for millions of Americans during the NAFTA-stoked ‘90s. But fast food and buffet-line steaks weren’t the only thing on the menu.

Over the years, Golden Corral periodically advertised an “Oceans of Shrimp” promotion. And where does all that shrimp come from? Like Atlantic salmon, tilapia and shellfish, it’s drawn from around the world. In fact, as Mashed recently detailed, “Thailand accounts for the majority of shrimp imported to the United States, and its system is rife with human rights abuses,” with “20-hour workdays,” “child labor and physical abuse,” and with “a large portion of farmed Thai shrimp … handled directly or indirectly by trafficked laborers.” Ecuador and Vietnam also fill Americans’ plates with this food item that was once considered a luxury but now can be consumed in abundance.

Even the “All-American” beef we’re eating might not be as American as we think. The folks at Farm Aid, which arose out of the aforementioned farm crisis of the ‘80s, recently pointed out that meat marked “Product of the USA” may “have been raised and processed in Brazil or New Zealand.” As CBS News explained, “imported beef products can be labeled ‘Product of the USA’ as long as it’s been minimally processed or repackaged in a U.S. Department of Agriculture-inspected facility.” Farm Aid advocates the end of this sleight of hand in favor of more truth in advertising. In the meantime, the Amazon rainforest is being cleared to raise more cows.

From Fast Food to Faster Fashion

If you are not familiar with the term “fast fashion,” you’re probably familiar with its purveyors. It often carries designer labels and is sold through major retailers like GAP, Urban Outfitters, H&M and Forever 21. Investopedia defines it as “clothing designs that move quickly from the catwalk to stores to take advantage of trends,” thus allowing “mainstream consumers to purchase the hot new look or the next big thing at an affordable price.” Fast fashion relies on “cheaper, speedier manufacturing and shipping methods,” which is why it is often made in sweatshops in places such as Bangladesh, where a series of deadly fires exposed the problematic disposability of its workers. Bangladesh’s garment workers often toil 12 hours per day, and sometimes 72 hours straight, according to The World Counts, for $92 per month. And it’s all done to feed the fast fashion fancies of U.S. shoppers.

International customs and brokerage firm AFC International tracks the fashion supply chains that link U.S. consumers, and profit-hungry corporations, to the world. Clothing tops the list of products imported to the U.S., with footwear, furniture, appliances and cars following in that order. Of course, China, thanks in part to its brutalized Uyghur workforce, is the leading source of imported clothing, accounting for “36.49 percent of U.S. apparel imports” and “84.95 percent” of imported footwear. Thanks to Nike, Vietnam is the runner-up in both imported footwear “with 6.46 percent of the U.S. import market,” and apparel with “10.4 percent of total U.S. imports.”

Not all these countries allow their workers to be as disposable as those in Bangladesh. But the clothing they produce is no less disposable. That disposability is more of a feature than a bug. Rapid turnover translates into more buying and more profits. The race to keep up also means less long-term planning and tons of excess inventory. Sadly, 59,000 tons of the unwanted byproduct is dumped annually in a Chilean desert. And that’s just one of the dumping grounds for excess clothing. Ghana, too, is a final destination for the fashion that comes in and out of the U.S. market with alarming speed.

It’s a model also reflected by the landfilling churn of “fast furniture.” Design Excellence describes it as “furniture that is made quickly and meant to last for a short period of time [and] is meant to be on trend and break quickly so that you can toss it and purchase the next trendy piece of furniture.” And we are tossing it by the ton. According to Environmental Protection Agency statistics, the annual amount of discarded “furniture and furnishings” has nearly doubled since 1990, when 6.8 million tons went to the landfill. Since 2015, over 12 million tons has been discarded each year.

Prime Movers

“There’s more to Prime. A truckload more.” That’s the tagline you’ll see emblazoned on the back of many Amazon trucks. But is “a truckload more” what we actually need? Apparently not, because the pandemic-stoked surge in online purchases has generated a surge in returns.

CNBC reported that “retail returns jumped to an average of 16.6% in 2021 versus 10.6% a year ago,” with a staggering $761 billion in merchandise sent back to stores and warehouses. As the conversion rate optimization company Invesp notes, “at least 30% of all packages ordered online are returned as compared to 8.89% in brick and mortar stores.” That matches the data reported by The Atlantic in a piece detailing the terminus of many of those returns, which is yet again the landfill. If you add the massive amount of oil and gas it takes to ship these items, which are often petroleum-based plastic products, the environmental and climate impacts of this back-and-forth is staggering.

The one thing all of these supply chains have in common is oil. It’s omnipresent, from the oil it takes to extract and ship more oil and other resources, to the oil it takes to make the plastics and petrochemicals that become a plethora of plastic products, to the oil it takes to run the factory farms and the manufacturing plants that pump out the goods that, thanks to oil-based shipping, eventually make it to our homes and businesses. It’s even making it into our bodies through petroleum-based microplastics.

Oil is the cornerstone of post-WWII foreign and defense policy, and U.S. taxpayers essentially subsidize the unabated flow of oil by funding a globe-spanning empire. Much like the old adage about “all roads leading to Rome,” the U.S.-built Empire of Consumption depends on all supply chains leading to home. With the rise of online shopping, that’s now quite literally true for most Americans. With the click of a button, a vast, oil-slicked supply chain delivers products directly to our doorsteps.

That is, before a shocking amount of those “easy as one-click” orders end up in landfills, right next to the 108 billion pounds of food the U.S. discards every year. This ever-faster churn is how the Empire of Consumption fills the bottomless pit of plenty. It’s also how neoliberal economics relies upon cheap labor and plasticized disposability to perpetuate the illusion of never-ending growth.

That illusion, which depends upon a cocktail of cheaper and cheaper products and more and more debt to give Americans the false sense of an increasing standard of living, was broken by the pandemic’s disruption.

That disruption is a Don’t Look Up-style warning about the unsustainability of a global system that acts like a conveyor belt feeding a heretofore bottomless pit of consumer desires… desires that are, in turn, crucial to justifying the continuation of an insatiable empire that denudes the planet, alters the climate and exploits labor around the world.