A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Tuesday, February 1, 2022

Urea Phobia and Organic Disaster: Catastrophic Economic Outlook

1 February 2022

Fertilizers can make or break a farm. Farming systems and practices have evolved from farmers’ experience and technological advancement over a long period of time. Any sudden changes by government regulations can result in serious adverse social and economic impacts. Sri Lanka has more than 2000 years of agricultural history.

Hence, farmers possess a significant amount of traditional knowledge for growing crops successfully. The Green Revolution in the 1950’s made significant changes to agriculture globally by introducing new technologies such as crop breeding and agro-chemicals to enhance food production to meet the ever-increasing demand. The mass scale urea production and usage were a result of that effort.

According to science, one major limiting factor for crop growth is nitrogen. The green leaves (chlorophyll) are made up of nitrogen.Since the 1950s, humans have doubled global nitrogen availability for crops by applying nitrogen fertilizers.

What is urea

Urea is a common type of nitrogenous chemical fertilizer used globally. Urea is made from natural ingredients of nitrogen from air (air is composed of almost 80% nitrogen), hydrogen (derived from natural gas) and carbon dioxide (www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/haber-bosch-process). The chemical formula for urea is CH4 N2O. Urea does not contain any heavy metals or human toxicants. Urea can be mixed with straw and fed to cows with no ill-effects. Urea comes in small dry granules and is usually packed in bags. Its transportation, storage, and applications are very easy and simple compared to liquid forms of fertilizers. Hence, urea is recognized as the “king” of fertilizers.

Global context

The world’s leading agricultural countries, such as Israel and the Netherlands, use a massive amount of urea. Switzerland was identified as the largest supplier of Urea to Israel, comprising 43% of total imports. Russia came in second with a 14% share of Israel’s total imports. It was followed by the US, with a 12% share. Countries with the highest volumes of urea production in 2020 were China (26 million tonnes), India (25 million tonnes) and Russia (9.6 million tonnes), with a combined share of 42% of global production. Levels of chemicals fertilizer used in a scale of kg per hectare are listed online by county statistics database Index Mundi

(www.indexmundi.com/facts/indicators). According to this source, Singapore uses the highest amount of chemical fertilizer in the world, whereas Sri Lanka falls at 68th.

Interestingly, no major agriculture producing countries have identified urea as a food toxicant and has imposed sanctions over its usage.

Fate of urea in soil

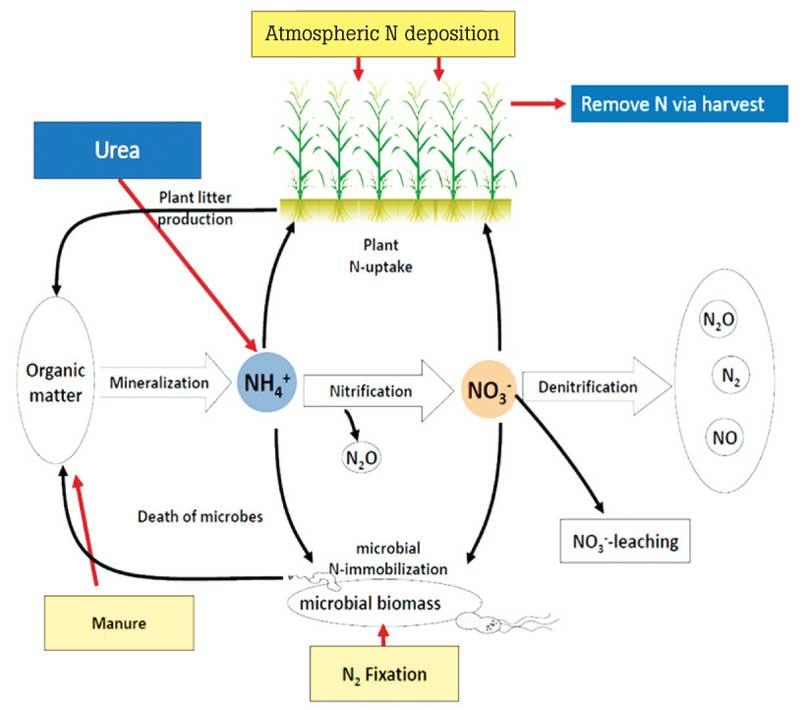

When urea is applied to soil, chemical reactions such as “hydrolysis” occur with water and the chemical changes into ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3-). Ammonium and nitrate are forms of nitrogen that crop can consume. All forms of nitrogen fertilizer (chemical or organic) need to be transformed into ammonium or nitrate in the soil so that crops can absorb them via their root system as part of the crops food. The crop is indifferent to the type of fertilizer applied to soil.

Fate of nitrogen

(N) in soil

Ammonium generally sticks to soil particles and does not readily move out of the soil. However, nitrate dissolves in water and so is easily washed down, potentially polluting groundwater, and river water. This is a major environmental concern world wide as this can lead to excessive weed growth (eutrophication) and harm fish and other living creatures in the waterways. High nitrate levels in groundwater can also cause problems in newborn babies (blue baby syndrome which is not reported in Sri Lanka). The World Health Organization’s recommended maximum limit for nitrate in drinking water is a relatively high, with a concentration of 50 mg/Litre (50g in 1000 litres of water). Nitrate levels in Sri Lankan groundwater water, however, is not a major environmental concern at the moment. Apart from possible nitrogen pollution in waterways, there are no other major bad environmental issues with using urea as a fertilizer.

Currently, Europe, USA, New Zealand and Australia have serious issues with nitrogen pollution in waterways, but a fertilizer ban has never been implemented due to the importance of urea being a reliable, cost effective, chemical fertilizer.

Sri Lanka’s Chemical Fertilizer ban

Amidst this backdrop, Sri Lanka’s ban on the chemical fertilizer imports lacks logic and scientific explanation. The claims that urea usage in agriculture has led to food poisoning and related health issues lacks adequate substance and proof. According to research conducted thus far, Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is not related to nitrogen fertilizers. The evidence-based information suggests that the drinking water from shallow wells is the major contributor to CKD. Therefore, providing alternative drinking water sources must be considered. The blame on chemical fertilizers uses such as urea appears to be incorrect based on the assumption that it is related to kidney disease.

Sri Lanka has very limited land area available for agriculture;the average farm size is in fact less than one acre. Therefore, intensive agriculture is practiced (2 or 3 crops per year) in order for farmers to make a reasonable living. This intensive agriculture continuously removes the nitrogen in soil in a rapid way.The replacement of this depleted nitrogen is vital to maintain productive crops. The most efficient, convenient, and effective way of replacing this nitrogen is to add chemical fertilizers such as urea.In such context, changes to regulations on the use of urea needs careful consideration and planning. Challenges in fully organic agriculture policy.

There is no doubt that organic agriculture is a great concept, but it needs specific management plans and a reasonable time-frame for system change to be effective. Farmers should be given options and crop types;specific cropping systems and markets should be established for organic products. The consumption of organic product is considered a luxury reserved for wealthy demographics. When a large portion of a population is likely to become malnourished from the much lower crop yields of organic farming, it does not seem a logical agriculture option.

Agricultural research worldwide clearly indicates that yields from organic crops are considerably lower than chemically fertilized crops such as those grown using urea. Mathematical modelling and computer-based simulation techniques are commonly used to understand the impact of fertilizer use on crop yield. A simulation scenario conducted using historical climate data with no chemical fertilizers, clearly indicated long-term yield reductions as shown in the following graphic (blue bars-crop yield, green line – crop nitrogen stress index).

The adverse impacts are likely to take a few years to show up as the native soil fertility runs down with continual export of nitrogen in the harvested component of the crop (grain, fruit, or leaf). In the absence of adding fertilizers, all the crops (e.g., rice, tea, vegetable, fruits, minor export crops etc.) will have significantly less production over time. Sri Lanka simply cannot afford for this to happen.

There is no guarantee that organic fertilizer can be risk free. Generally, organic fertilizer is made from animal wastes or green residues. Many countries such as China use the remaining solid component of the sewage treatment process (bio-solids) as an organic fertilizer. But modern sewage often contains toxins such as heavy metals and fluorine substances that concentrate in the bio-solids. While this can be used in non-food crops such as forests, its usage for food crops should be carefully monitored and managed. Australia is considering halting bio-solid applications to land due to harmful chemicals.

Finally, it is not as cost-effective as it claims to be. Decomposed organic material, often called a soil enhancer rather than fertilizer has less than 2% nitrogen. Based on nitrogen content, around 25 bags of organic materials are required to replace one bag of Urea. The handling, storage, transport, and application of those organics will have a massive labour demand, and it is far too costly for typical subsistence farmers. Furthermore, the area needed to produce the organic matter will easily exceed the area used for food production. Applying excessive organic matter into soil has a detrimental effect on crop growth.

Considering all of the above challenges, imposing fully organic agriculture practice is not affordable for Sri Lanka.

The Way Forward

Thus, it is important to take these concerns into consideration prior to making swift and sudden policy changes. A shift in agriculture policy requires specific management plans and a reasonable time-frame for system change to be effective. Using science and technology in understanding the problem and finding a solution is important. Appropriate technical and scientific advice for changing agricultural policies must be sought and taken from suitably qualified persons and institutions. Sri Lanka’s finest organizations such as the Department of Agriculture and research institutes for rice, tea, rubber, and coconut must be coordinated for advice before any major policy change involving the use of fertilizer is made.

Most importantly, farmers should be given options and crop types; specific cropping systems and markets should be established for organic products. The consumption of organic product is considered a luxury reserved for wealthy demographics. When a large portion of a population is likely to become malnourished from the much lower crop yields of organic farming, it does not seem a logical agriculture option.

In the light of the on-going COVID-19 pandemic reducing tourism, agriculture is the only remaining economic lifeline for Sri Lanka to sustain its national Gross Domestic Production (GDP). Banning fertilizer imports at this point will be detrimental to the nation’s GDP and food security. Such thoughtless policies also have the risk of repeating the failures of 1970s during when then political administration of the time imposed impractical agriculture policies that led to government change in 1977.

Urea phobia is purely hypothetical. There is no scientific basis to support any adverse human health impacts from using urea to grow crops. In a context where more than 90% of world population consumes food grown with chemical fertilizer without ill effect, we should not make speculations on the usage of chemical nitrogen fertilizer. Given how Sri Lanka’s life expectancy has improved over the years, on what basis can we blame the use of urea on the reduced quality of life? While there is no argument on the benefits and importance of organic farming, such policies should only implement while complementing with the mass agriculture. If not, the agricultural productivity clock back to the first half of the 20th century, during when the South Asian region experienced widespread malnutrition.

The writer is a Principal Scientist at the Queensland Department of Environment and Science based in Australia, can be reached on sunil.tennakoon@gmail.com or on mobile ++61405320080.