A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Sunday, June 12, 2022

Explained: Renewed Israel-Lebanon maritime border dispute

Tensions are rising between Israel and Lebanon over their maritime border after arrival of Israeli-contracted exploration vessel in disputed area

A tug pulls an Energean floating production storage and offloading ship along Egypt's Suez Canal, on 3 June 2022 (AFP)

By Dario Sabaghi- 11 June 2022

The arrival of the Israeli-contracted Energean Power vessel on the maritime border between Israel and Lebanon on 5 June has brought a long-running maritime dispute between the two countries to the surface, precipitating new tensions in the region.

Following the arrival of the Energean’s floating production, storage and offloading (FPSO) unit to the disputed waters to develop the Karish gas field for Israel, Lebanese President Michel Aoun and Prime Minister Najib Mikati warned Tel Aviv against Energean launching operations to develop Karish, located in a disputed area, while Hezbollah threatened the use of force to protect Lebanon's natural wealth, prompting fears of a violent escalation.

Lebanese officials said US senior energy adviser and mediator Amos Hochstein will visit Beirut early next week to relaunch indirect maritime border negotiations, which had stalled over Lebanon’s claim that the map used by the United Nations in the talks needed modifying.

As tensions rise once more around the demarcation of maritime borders between Israel and Lebanon, Middle East Eye explains all you need to know about the dispute.

Timeline

The maritime dispute between Israel and Lebanon dates back to 2007, when a bilateral agreement between Lebanon and Cyprus over the delimitation of their maritime borders left open the possibility of amending a maritime zone between Israel and Lebanon.

Although Cyprus ratified the agreement in 2009, Lebanon did not.

In 2010, Israel signed an exclusive economic zone agreement with Cyprus, taking the coordinates subject to the amendment within the Cyprus-Lebanon agreement as its northern boundary, outlined in its agreement with Nicosia.

'Bringing Line 23 to negotiations would mean ceding part of the Karish field to Israelis and reducing the areas… that belong to Lebanon'

- Marc Ayoub, energy researcher

As a result, Israel's claimed northern maritime border overlapped Lebanon's southern one, creating a dispute between the two countries, with Lebanon denouncing the agreement as an attack on its sovereign rights over that zone.

Israel, however, deposited its coordinates to the United Nations in July 2011.

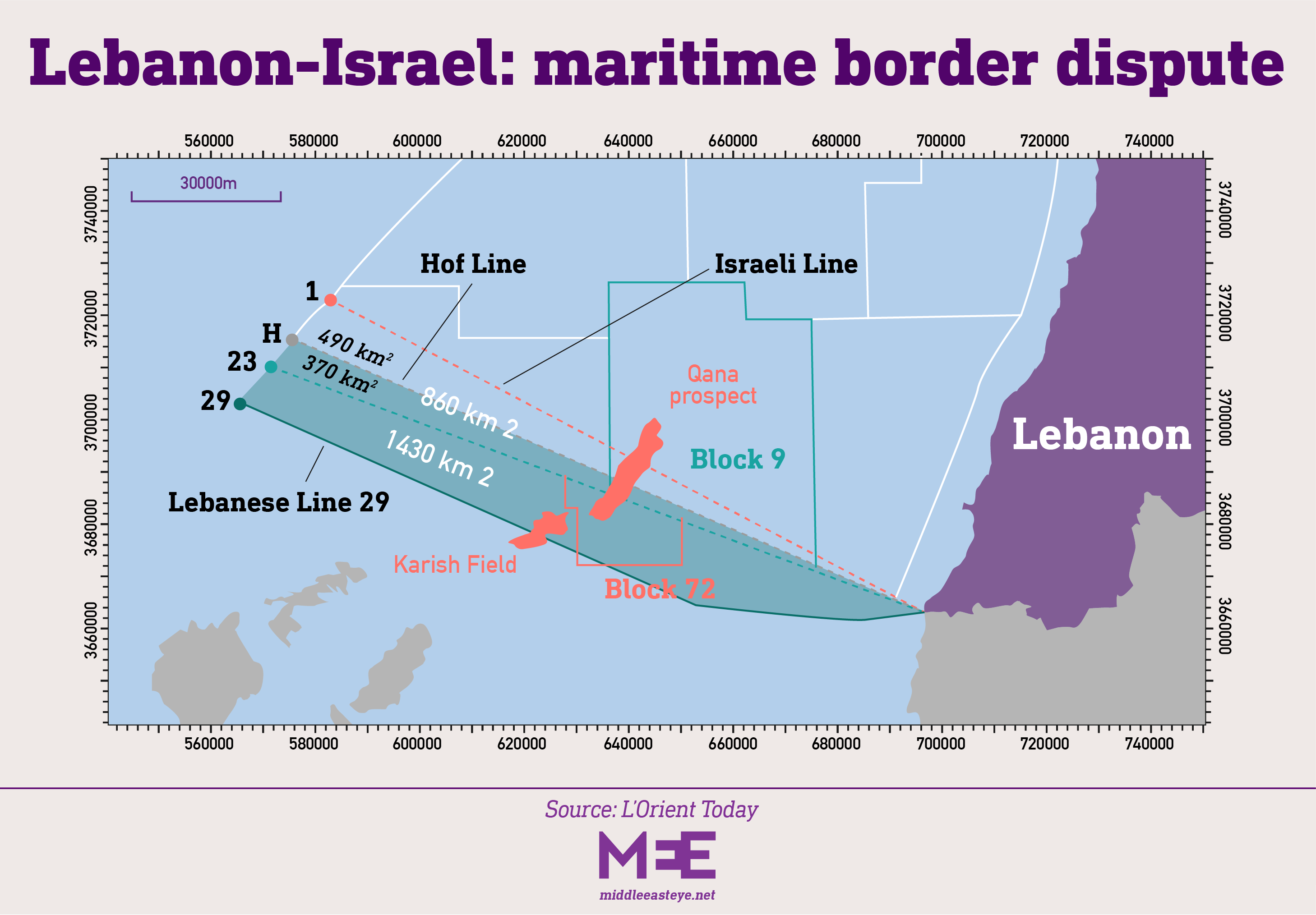

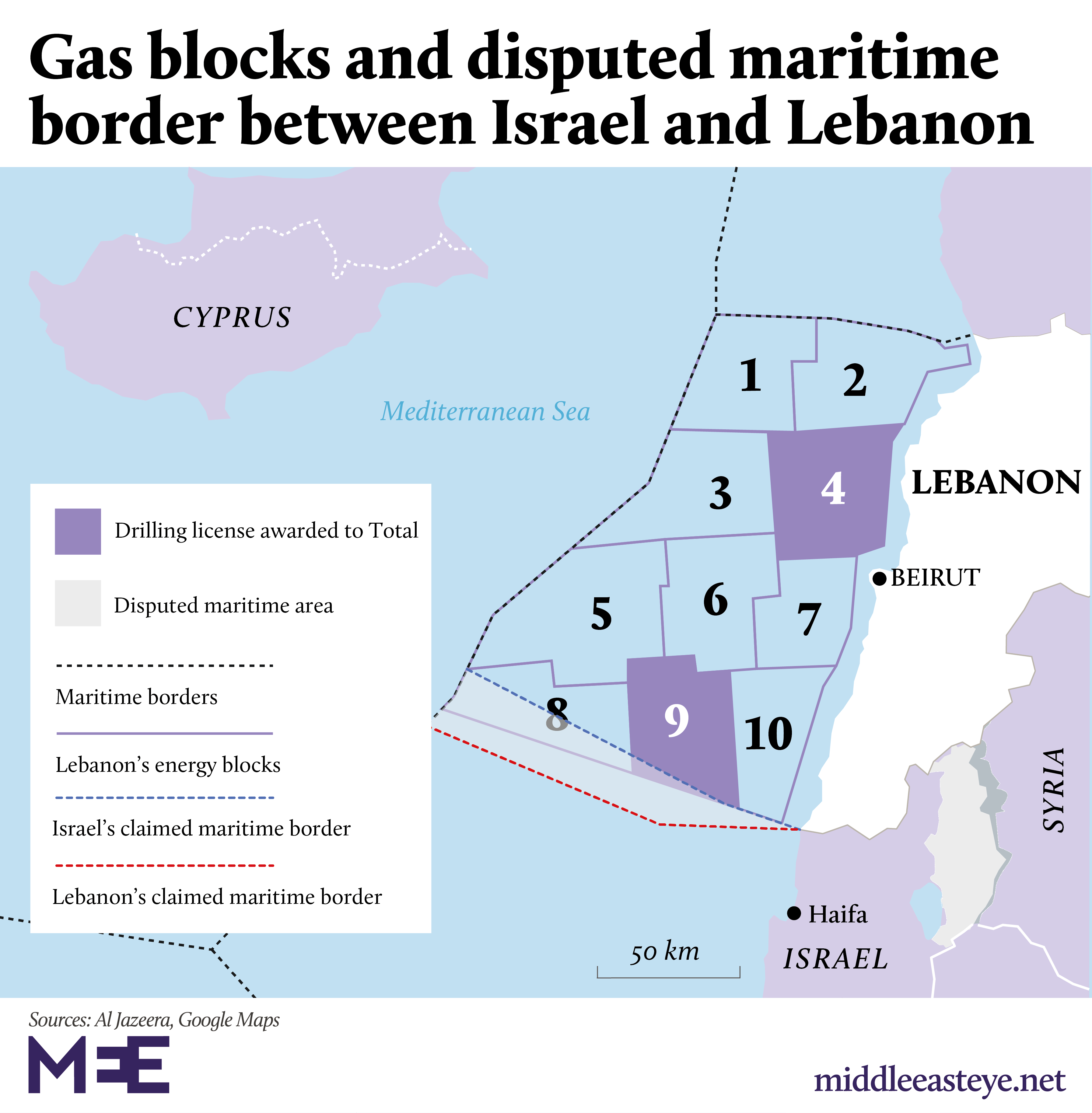

The dispute over the 860 square kilometres gathered momentum in late 2017, when Lebanon signed a gas exploration and production agreement with a consortium comprising the French company Total, the Italian Eni and the Russian Novatek for gas blocks 4 and 9.

Exploration of Block 4 was declared unviable commercially, but seismic surveys showed promising results for Block 9, although only drilling could confirm the presence of commercially viable gas resources.

However, even though committed to its exploration deal with Lebanon, Total stressed that it would not start operations on Block 9 until the Israeli-Lebanese maritime dispute was resolved.

The Karish field

Israel's announcement in June 2020 of its third offshore bidding round for oil and natural gas exploration of Block 72, located within the disputed area between Line 1 and 23, led to the start of US-brokered indirect talks, which eventually stalled.

Today, the Israelis claim the right to operate on the Karish field because Lebanon's maritime boundary is set on Line 23, which does not intersect with the gas reservoir.

However, Roudi Baroudi, an energy industry expert and chief executive of Energy and Environment Holding, told Middle East Eye that both Lebanese and Israeli calculations of the demarcation of their maritime borders were inaccurate. Baroudi said both Lebanon and Israel calculated the coordinates starting from offshore, whereas they should have drawn their delimitation lines from the Land Terminus Point (LTP), defined as a straight line perpendicular to the general direction of the coast near the land border terminus.

"Lebanon drew its Line 23 starting from the sea, around 60 metres from the coast. Israel drew from 30 metres from its coast. These calculations are technically wrong. The current technology has demonstrated that what Israel is claiming is not right.”

But Frederic Hof, the US diplomat in charge of mediations between Israel and Lebanon from 2010 to 2012, told MEE that both Israeli and Lebanese delimitation lines were valid.

"Over 10 years ago, my team from the US Department of State and I spent a lot of time on how those calculations were made,” he said. “We were convinced that each party did a systematic job. They used different criteria for reference points, but both lines were valid.”

In 2011, Hof proposed to then-Prime Minister Mikati the attribution of 55 percent of the disputed area to Lebanon and 45 percent to Israel. However, both Israeli and Lebanese officials refused the proposal of the so-called "Hof Line”.

"My feeling is that if Mikati succeeded in accepting the compromised line that we proposed, Lebanon today would be reaping tens of billions of dollars in revenue from gas," he said.

Line 29

According to studies conducted by the Lebanese army and endorsed by the UK Hydrographic Office, Lebanon could claim a further 1,430 square kilometres. The new delimitation, Line 29, would break into the Karish field.

However, Lebanon has yet to amend Decree No. 6433, an official document issued to the United Nations in 2011 that indicates the coordinates of Line 23 as the country's southern maritime border.

Why the Lebanese state has not yet amended the decree is a million-dollar question for Diana Kaissy, energy governance expert and advisory board member of the Lebanese Oil and Gas Initiative (LOGI).

She told MEE that when parliament speaker Nabih Berri announced the indirect talks in June 2020, Lebanese officials decided to continue negotiations using the unamended decree, even though Lebanese negotiators had informed the Lebanese president about the Lebanese army's study that suggested adopting Line 29 for the country's southern boundary.

"What is really sad about this situation is that we are still using the decree that reports Line 23. We, the Lebanese, are to blame because we haven't modified it and adopted Line 29,” Kaissy said. “We still don't agree on what our maritime borders are.”

Energy researcher Marc Ayoub said that the government led by Hassan Diab was due to amend the decree in the summer of 2020. However, when Diab resigned following the Beirut port blast on 4 August that year, Aoun refused to sign a decree issued by a caretaker government.

Additionally, the president said that Lebanon was in the middle of negotiations with the United States and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for an economic recovery package, and for a US-brokered electricity deal with Egypt and Jordan.

"President Aoun initially supported the proposal of Line 29. But after the formation of the Mikati government in September 2021, he changed his mind, and in an interview with local newspaper Al-Akhbar he said the right southern maritime boundary of Lebanon is Line 23," Ayoub told MEE.

The US role

Hochstein’s visit to Beirut in February 2022 and his proposal, which suggests starting Lebanon's negotiations from Line 23 instead of Line 29, might have led Lebanese officials to refrain from amending the decree, for fear of losing Washington’s support in other negotiations.

'International companies need to have a sense of political certainty and calm to make major investments in gas exploration'

- Frederic Hof, US diplomat

At the same time, however, the Lebanese government has yet to give Hochstein an answer regarding his proposal.

The US role in the mediation between Israel and Lebanon highlights the importance of the maritime dispute, not only for the two parties involved but also for the region.

In fact, the US interest is to resolve the dispute to avoid an escalation in the region.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is already draining energy from US foreign policy, which is currently focused on China.

Hof told MEE that the United States is trying to provide good offices to avoid conflict.

"It is a potentially dangerous situation. This could only work diplomatically. What is really needed for Lebanon's political leaders is to establish a clear position for the Lebanese state. This doesn't exist right now, and the dispute contributes to the uncertainty and instability.”

Golden opportunity for Lebanon

According to Kaissy, if Lebanon quickly resolves the maritime dispute with Israel, starts gas exploration and exploitation activities in its exclusive zone, and finds commercial reservoirs, it still has time to develop a pipeline.

This could be a golden opportunity for a country severely hit by a rampant economic crisis since 2019, given that the European Union will massively invest in renewable energy, with gas being classified as a green investment, following the Green Deal and its detachment from Russian gas.

For Baroudi, Lebanese gas can boost the Lebanese economy and provide people with basic social benefits, including healthcare, education and electricity.

However, Ayoub thinks that the only way to go back to the negotiations with Israel is to amend the decree.

"It is our waters. We cannot go back to the negotiations while being weak,” he said.

“Bringing Line 23 to negotiations would mean ceding part of the Karish field to Israelis, sharing the Qana gas field with Israel and reducing the areas of blocks 8 and 9 that belong to Lebanon.”

Israel’s gas exploration industry

Unlike Lebanon, Israel has been involved in the gas exploration industry for decades. After relying on imports for years, Israel began producing natural gas from its offshore gas fields in 2004.

Following the conflict in Ukraine, Israel is renewing offshore natural gas exploration. The Ukraine war has triggered Europe's need for a quick replacement of its previous supply from Russia.

Therefore, the European demand has led Israel to prepare a new round of tenders for gas exploration off its Mediterranean coast to export gas to Europe, even though Israeli Energy Minister Karine Elharrar recently announced that explorations for new gas fields would be put on hold to focus on meeting renewable energy targets.

Israel aims to double its natural gas production to 40 billion cubic metres by expanding existing projects and bringing new ones online, such as the Karish gas field, to meet European demands.

In such a context, Israel wants to secure the Karish gas field and resolving the maritime dispute could be advantageous for Tel Aviv.

For Hof, it would be impracticable for Lebanon to start negotiations claiming to start from Line 29, but as long as the negotiations focus on the disputed area between Line 1 and Line 23, both parties can find a solution.

"The current US proposal would be treating the entire disputed area as one single unified entity. If both sides agree, one single company can exploit, and the company could provide revenue to both sides on a 50-50 basis,” he said. “Another option would be to divide the area into two exclusive economic zones according to the resolution of negotiations.”

Asked whether the maritime dispute could escalate, Hof told MEE that this scenario is not in the interests of either Israel or Lebanon.

"International companies are already nervous about this situation, and they need to have a sense of political certainty and calm to make major investments in gas exploration and exploitation," he said.