A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

A Brief Colonial History Of Ceylon(SriLanka)

Sri Lanka: One Island Two Nations

(Full Story)

Search This Blog

Back to 500BC.

==========================

Thiranjala Weerasinghe sj.- One Island Two Nations

?????????????????????????????????????????????????Wednesday, August 31, 2016

SRI LANKA’S TRANSITIONAL MOMENT AND TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE – RUKI FERNANDO

(Light among the darkness: Hindu religious festival in Colombo July 2015 ©s.deshapriya)

Within the first month after winning the parliamentary elections in

August 2015, the new Government made a series of commitments related to

transitional justice. These were articulated through a speech by the

Foreign Minister at the 30th session of the UN Human Rights Council.[1] These

commitments were also reflected in the resolution on Sri Lanka that was

adopted by the Human Rights Council on 1 October 2015.[2] The

resolution came just after the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

had published a report which alleged war crimes and crimes against

humanity and other serious violations of international human rights and

humanitarian laws, by both the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE.[3]

Government’s commitments

The present Government’s commitments included setting up an Office of

Missing Persons (OMP), a Commission for Truth, Justice, and Guarantees

of Non-reoccurrence, a Judicial mechanism with Special Counsel, which

will have the participation of foreign judges, prosecutors,

investigators and defence lawyers, and an Office for Reparations. The

Government also committed to reduce the military’s role in civilian

affairs, facilitate livelihoods, repeal and reform the Prevention of

Terrorism Act (PTA), criminalise disappearances, ratify the Enforced

Disappearance Convention[4] ,

review the victim and witness protection law, and range of other

actions. Consultations to seek people’s views on transitional justice is

underway across the country, under the leadership of some civil society

activists.

The Enforced Disappearance Convention was ratified in May this year and

the draft Bill to create the OMP was passed by Parliament on 11 August.

There are positive features as well as weaknesses and ambiguities in the

Bill[5].

Due to a history of failed initiatives, the minimal ‘consultations’

that occurred during drafting process and the lack of information on

details, there appears to be very little confidence in the OMP amongst

families of the disappeared. This is likely to be the case for other

mechanisms, unless there’s a drastic change in approach from the

government.

Reactions to transitional justice within Sri Lanka

Currently, the transitional justice agenda appears to be polarising Sri

Lankan society. Opinion polls, and my own impressions, indicate that the

Tamil community, particularly in the North and the East, who bore the

brunt of the war, appears to favour strong international involvement.

But the majority Sinhalese community appears to reject international

involvement. Varying opinions have been expressed about forgetting the

past, memorialisation, prosecutions, and amnesty. There are also

different or contradictory opinions and expectations within each ethnic

community and amongst survivors of violations and families of victims.

The Government’s transitional justice commitments have been criticised

by the former President and his supporters. Even the release of a few

political prisoners, the release of small amounts of land occupied by

the military, and the establishment of the OMP to find truth about

missing persons have been framed as an international conspiracy that

endangers national security and seeks revenge from “war heroes”.

There does not appear to be an official Government policy document on

transitional justice. The Government’s commitments have only been

officially articulated in Geneva by the Foreign Minister and not in Sri

Lanka . The Foreign Minister has been the regular advocate and defender

of these commitments. Some of the meetings with local activists have

been convened by him and the Secretariat for Co-ordinating

Reconciliation Mechanisms (SCRM) is housed in the Foreign Ministry. All

these contribute to the process being seen as emanating and driven by

foreign pressure. Outreach on the Government’s transitional justice

plans appears to focus on the international community and not towards

Sri Lankan people.

The President and Prime Minister have not been championing the

Government’s official commitments. For example, the duo have publicly

stated that the commitment to have foreign judges in the judicial

mechanism will not be fulfilled. Even this has not satisfied the critics

alleging foreign conspiracy, and has disappointed some activists,

especially Tamils, as well as survivors and victims’ families.

Developments on the ground

Monuments erected to honour the Sinhalese dominated military during the

Rajapakse time continue to dominate the Tamil majority Northern

landscape. Army camps that were built over some of the cemeteries of

former LTTE cadres that were bulldozed by the Army after the war are

still there. The loved ones of those whose remains were in these

cemeteries have no place to grieve, lay flowers, light a candle, or say a

prayer. While the numbers have reduced from those under the Rajapaske

regime, intimidation and reprisals on families, attacks, and threats and

intimidation of activists and journalists continue to occur. Limited

progress on issues, such as the release of political prisoners, land

occupied by military, continuing military involvement in civilian

affairs in the North and East, reports of continuing abductions, and

arrests under the PTA have raised doubts about the Government’s

commitments.

Although a few military personnel have been convicted and some others

arrested on allegations of human rights abuses, the lack of progress in

thousands of other cases only reinforces calls for international

involvement for justice.

Towards Rights & Democratization beyond Transitional Justice framework

Unemployment, debt, and sexual and gender-based violence is widespread

in the former war ravaged areas. The new Government’s economic and

development policies are focusing on trade, investment, and mega

development projects, which privilege the rich and marginalise the poor.

Pre-war rights issues, such as landlessness, sexual and gender-based

violence and discrimination, caste, rights of workers, including those

working on tea estates, still need to be addressed.

A consultation process towards a new constitution drew a large number of

public representations, dealing with many of the issues mentioned

above. But the next steps are not clear, particularly in finding

political solutions to the grievances of the country’s ethnic

minorities.

The political leadership will have to reach out to all Sri Lankans,

especially to the Sinhalese majority, about its reform agenda, while

taking principled actions to win the confidence of numerical minorities

such as Tamils and Muslims. At the national level, the coming together

of the two major political parties and support of the two major parties

representing Tamils and Muslims, makes this a unique opportunity to push

towards radical reforms.

It will also be a challenge to go beyond a conventional transitional

justice framework and use the transitional moment to move towards

reconciliation, democratisation, and sustainable development, by

addressing civil and political rights as well as economic, social, and

cultural rights in a holistic manner, considering the yearnings of war

survivors, victims’ families, and the poor, for truth, reparations,

criminal accountability, and economic justice.

[1] Speech by Hon Mangala Samaraweera at the 30th session of the Human Rights Council, Geneva, 14 September 2015.

[2] Human

Rights Council Resolution, Promoting reconciliation, accountability,

and human rights in Sri Lanka, 14 October 2015, UN Doc. A/HRC/RES/30/1

(adopted 1 October 2015).

[3] Human

Rights Council, Report of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL),

thirtieth session, 16 September 2015, UN Doc. A/HRC/30/CRP.2.

[4] International

Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced

Disappearance, adopted 20 December 2006, UN Doc. A/61/488 (entered into

force 23 December 2010) (“Enforced Disappearance Convention”).

[5] For more on OMP, see http://thewire.in/42687/sri-lankas-disappeared-will-the-latest-missing-persons-office-bring-answers/

( First published in Inform news letter)

Govt. fast tracks the superstructure reform p

rocess

by Jehan Perera-August 29, 2016

The

constitutional reform process moving forward rapidly, though without a

high level of publicity, indicates that the government leadership has a

businesslike approach to political reform. It is reported that four of

the six subcommittees who were given different areas of constitutional

reform to deal with have handed in their reports to the steering

committee on constitutional reform headed by Prime Minister Ranil

Wickremesinghe, which is responsible for producing the draft

constitution. The subcommittees are on Fundamental Rights, Judiciary,

Law and Order, Centre Periphery Relations, Public Finance and the Nature

of the State. The government appears to be making the best use of the

opportunity that has presented itself in the form of the government of

national unity, which gives it a 2/3 majority in Parliament, capable of

getting even controversial legislation through. Some of the

constitutional reforms will be controversial, especially those

provisions that relate to the ethnic conflict. The absence of fanfare

may be because the government prefers to get those through the

parliamentary hurdle first before taking them to the people.

The

constitutional reform process moving forward rapidly, though without a

high level of publicity, indicates that the government leadership has a

businesslike approach to political reform. It is reported that four of

the six subcommittees who were given different areas of constitutional

reform to deal with have handed in their reports to the steering

committee on constitutional reform headed by Prime Minister Ranil

Wickremesinghe, which is responsible for producing the draft

constitution. The subcommittees are on Fundamental Rights, Judiciary,

Law and Order, Centre Periphery Relations, Public Finance and the Nature

of the State. The government appears to be making the best use of the

opportunity that has presented itself in the form of the government of

national unity, which gives it a 2/3 majority in Parliament, capable of

getting even controversial legislation through. Some of the

constitutional reforms will be controversial, especially those

provisions that relate to the ethnic conflict. The absence of fanfare

may be because the government prefers to get those through the

parliamentary hurdle first before taking them to the people.

The unique opportunity that has presented itself in terms of

constitutional reform is the existence of a government of national unity

that is formed by the partnership of the two major political parties,

the UNP and SLFP, which have hitherto always been on opposing sides of

the political divide. Never before have these two parties formed a

government together. One has always been in opposition to the other.

This has also meant that whenever a government led by one them tried to

come up with constitutional reforms or a political solution to the

ethnic conflict, the other party in opposition always tried to undermine

what the government was trying to do. Thus, both the 1972 and 1978

constitutions were essentially creations of one party, which those

governments bulldozed into law without the support of either the major

opposition party or the ethnic minority parties.

The inability of previous constitutional reform efforts to obtain a

bipartisan consensus, let alone a consensus that included the ethnic

minorities, was a fatal flaw that had catastrophic consequences to

inter-ethnic relations and eventually led to protracted civil war. On

this occasion, however, the government comprises both the UNP and SLFP

which has a large voter base that supports them politically. The

political support given to the government by the ethnic and religious

minorities at the last elections has also created a political obligation

on the part of the government to take their interests into account in

fashioning the constitutional reforms. Although the SLFP is for all

practical purposes divided, the official part of the SLFP is headed by

President Maithripala Sirisena, who is giving increasingly forceful

leadership to his more liberal faction of the SLFP.

NO FANFARE

However, the division in the SLFP means that a substantial number of MPs

and local level politicians are supporting the nationalist faction led

by former President Mahinda Rajapaksa. The existence of a nationalist

Sinhalese opposition to the government in the form of the Rajapaksa

faction of the SLFP appears to have pressed the government to steer

clear of engaging in mass politics regarding the legislative reforms at

this time. The government may be concerned that if the issues of

constitutional reform or the reconciliation mechanisms are canvassed too

strongly with the general population at this time, the nationalism that

exists within the country, and in all its communities in competing

ways, will lead to a rising tide of opposition from below which could

influence, or even include the members of the official SLFP. This may

explain why the government is proceeding with constitutional reform

without much fanfare or engaging in mass politics on it.

This same pattern can be seen in the case of the reconciliation process.

The government’s passage of the Office of Missing Persons Act (OMP)

through parliament was achieved at top speed that has now become a

problem as several legitimate amendments proposed by the opposition were

neither discussed nor voted upon. The government has itself admitted

that amendments proposed by the JVP, which is a party that itself caused

and suffered from disappearances in the era of its insurrection in the

late 1980s and early 1990s, were missed in the melee in parliament on

the day that the OMP bill was taken up for debate and rushed through to

ratification. The law regarding the OMP has also been criticized by

civil society groups for the reason that it has not been prepared in

consultation with victim groups and the civil society organizations that

have tried to sustain them.

In the case of both the constitutional reforms and the reconciliation

processes the government has shown it is interested in pursuing public

consultations but on a limited scale by civil society organizations

which have emerged as trusted intermediaries. The insights from this

process of consultation have been useful and are being incorporated in

the final drafts that the government is preparing for the new

constitution. But it does not take the message of what the government is

trying to do to the larger population. The government appears to be

keeping that for a later phase when it will have to actually champion

the reforms it is currently undertaking to win the hearts and minds of

the people. At the present time the general population remain more or

less as passive observers with regard to the two most important

political processes underway in the country without knowing too many of

the details as to what is happening in the country and why.

CIVIL SOCIETY

On the other hand, the political championing the reform process will

necessarily have to take place at the time a referendum on the

constitutional changes is called for by the Supreme Court. If there is

to be a political solution to the ethnic conflict, which is the long

unresolved and festering sore in the body politic, it is very likely

that it will entail a referendum as such a solution will include some

major changes to the constitution. At that point the government will

need to go all out to win the referendum. Losing a referendum on

constitutional change will have catastrophic consequences to the

government and to the polity itself on a scale that exceeds the Brexit

reversal in the UK. In the UK the prime minister felt obliged to resign

but the UK is under the same ruling party that is negotiating its exit

from the EU. However, if a referendum is lost in Sri Lanka, the

government’s mandate to govern will itself be eroded, rival nationalisms

will take the upper hand and ethnic relations will be sundered.

At the beginning of this year, the government provided civil society

with an opportunity to get involved in the constitutional reform process

by appointing a Public Representations Committee which was expected to

go round the country and gather the views of the people on the main

issues that require constitutional change. The PRC submitted its report

about three months ago in May to the Prime Minister who is chairing the

steering committee of the constitutional drafting process. The

government also gave civil society a similar opportunity to play an

intermediary role when it appointed the Consultation Task Force to

ascertain the views of the general public on the reconciliation

mechanisms it has proposed. This body has submitted an interim report on

the first of the reconciliation mechanisms, the Office of Missing

Persons, and is likely to submit the full report which includes the

other three reconciliation mechanisms soon.

In the interim period civil society organizations that focus on peace

building, human rights and good governance are seeking to influence the

drafting of the legislation relating to constitutional reform and the

reconciliation mechanisms in order to improve them. Civil society needs

to also engage in an awareness creation and education campaign with its

own networks of partners at the community and grassroots levels. Such a

course of action will ensure that a network of conscientised opinion

formers will be available in all parts of the country to give their

support to the government’s campaign when it has to face the referendum

on constitutional reform and implement the reconciliation mechanisms

that it has passed into law. The changes in the superstructure of laws

and institutions need to be accompanied by corresponding changes in the

attitudes of the general population whose thinking has been conditioned

by decades of nationalism, over centralization of power and focus on

national security-centered policies which were justified as necessary in

a time of war.

A New Truth Commission for Sri Lanka: Lessons from Other Models

August 26, 2016

Written by Akshan de Alwis, UN Correspondent

William Blackstone, perhaps the most influential jurist in Western legal thought, claimed in his 18th century magnum opus Commentaries on the Laws of Englandthat

“It is a settled and invariable principle in the laws of England, that

every right when with-held must have a remedy, and every injury its

proper redress.” Providing remedy for infringed-upon human rights has

become one of the fundamental means of realizing the massive framework

of human rights developed over the past century. From this goal of

redressing violations has arose a novel perspective of justice –

transitional justice.

William Blackstone, perhaps the most influential jurist in Western legal thought, claimed in his 18th century magnum opus Commentaries on the Laws of Englandthat

“It is a settled and invariable principle in the laws of England, that

every right when with-held must have a remedy, and every injury its

proper redress.” Providing remedy for infringed-upon human rights has

become one of the fundamental means of realizing the massive framework

of human rights developed over the past century. From this goal of

redressing violations has arose a novel perspective of justice –

transitional justice.

Transitional justice is a broad and amorphous term; it covers far too

many concepts and ideals to be fairly surmised in a single essay, let

alone a paragraph. Under the umbrella term of transitional justice range

the Nuremburg and Tokyo Trials to an annual prayer ceremony in Northern

Uganda as equally legitimate forms of post-conflict justice.

Nonetheless – from the numerous disparate definitions and

materializations of transitional justice – a basic binding thread

between the various visions can be found: the question of, as noted by

Priscilla Hayner, “how to reckon with massive past crimes and abuses?”

In the realm of traditional jurisprudence, this question is

self-evident: crimes are addressed by criminal justice. However, in the

case of many transitioning states, the criteria for a stringent criminal

justice system can rarely be met in dealing with the legacy of human

rights abuses. The rules of evidence may be impossible to meet,

witnesses may not be willing to testify in an adversarial system, and

the political situation may not allow for a truly free and independent

trial. The nascent norm of transitional justice attempts to address

these roadblocks with a litany of tools for a diverse set of demands and

circumstances. Memorialization, reparations, lustration, and

commissions of inquiry are some of the many manifestations of

transitional justice. But the dominating force in transitional justice

is that of the truth commission, which has become the international

community’s cure-all for transitioning states.

While the initial batch of truth commission experiences were middling,

by increasing the disciplinary scope of the process, a more robust and

successful model has precipitated over the last decade. Instead of

thinking of a truth commission as a salve or a temporary measure to heal

an injured body politic, the modern truth commission sees

reconciliation, truth-building, and societal reconstruction as a

constantly ongoing process. The mandate of transitional justice is never

truly over: the phantom pain of conflict can never fully be healed;

even generations later, the scars of conflict will remain.

Given these seemingly endless complexities and near-impossible mandate,

what can a truth commission hope to achieve? To answer this question

requires an understanding of the evolution of the truth commission. By

examining the width and breath of truth commissions, a holistic vision

of a truth commission can be developed that eschews easy description and

instead realizes the multidisciplinary potential of transitional

justice.

While the Nuremberg Trials are perhaps the first example of transitional

justice, they bare as much resemblance to the modern truth commission

as fish to man. Despite the claims that war crimes tribunals, truth

commissions, and commissions of inquiry are all Western constructs

designed to suppress the developing world, the first truth commissions

emerged out of the “global south.” The progenitors of the truth

commission were not a result of Western pressure, but instead of

incalculable grief in developing nations emerging from conflict. The

first official truth commission was in Bolivia, but it would take

Argentina in 1984 to pioneer the truth commission with the Nunca Más

(Never Again/No More) report. Just the name of the report itself

highlights the visceral anguish that the first truth commission

attempted to mitigate. While not necessarily truth commissions in name,

inquiries into previous war crimes were undertaken in Uganda, Zimbabwe,

Guatemala, El Salvador, Nepal, and the Philippines.

The Rettig Report, officially known as the National Commission for Truth

and Reconciliation Report in Chile, was the first of these kind of

bodies to formally adopt the language of “truth and reconciliation.” But

the climactic development point for the truth commission is most

definitely that of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission

(TRC).

Although it may have formally appealed to Western concepts of human

rights, the TRC deployed an organic model of state, culture and society.

Drawing on Plato’s views of society, the body politic is viewed through

general principles of organicism, holism, and collectivism in which it

is the purpose of the individual to maintain social harmony and the

health of the state. This perspective is exemplified in the writings of

TRC Chair, Desmond Tutu. In justifying the controversial amnesty

legislation, which enabled the commission to grant amnesty to

perpetrators, Tutu writes:

Social harmony is for us the summum bonum – the greatest good.

Anything that subverts or undermines this sought-after good is to be

avoided like the plague. Anger, resentment, lust for revenge[…] are

corrosive of this good.

The main metaphor of the organic state is society as a sick body that is

in need of healing. The TRC carried out this healing and thus promoted

national reconciliation. Metaphorically phrased, the TRC opened the

wounds of the suffering nation and cleansed them, thus healing the

national body politic. The morality of the nation-state becomes a

question of Platonic moral and political hygiene. Here, the focus is not

as much on individuals, but on the nation-state. Reconciliation between

individuals in the sense of victim–offender mediation was not attempted

in South Africa; sub-national social groups such as classes, races or

genders are not to be reconciled with one another either. Instead, the

reconciliation proposed by the TRC works at a much higher level of

abstraction. The nation-state is to be reconciled with itself.

Ultimately, the TRC is but another tool to respond to the classic

Weberian problematic of state legitimacy.

But South Africa’s truth commission served a vital tool. It was the

standard model to which each subsequent truth commission was held to,

allowing for transitioning societies to fork their own vision of

transitional justice. It became a platform for a vibrant and diverse set

of transitional justice forms, each suited for the individual situation

of each nation. The modern truth commission does what South Africa did

not: focus on the individual, vulnerable groups, and rich narratives

that refused to bend to politics.

Nowhere is this modern truth commission perspective more visible than in

Timor-Leste. Reeling from years of Indonesian occupation, the Timor

Leste developed a Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation

with the help of the United Nations. Its main work in East Timor was to

carry out Community Reconciliation Procedures (CRPs) in every district,

with the aim of reintegrating low level offenders. The framework chosen

to shape these meetings was the adat (customary law) ceremony called “biti bot”

or “unrolling of the mat.” The mat is laid out in a public space and

the occasion is dignified by the display of sacred heirloom objects. The

meeting is presided over by elders and spiritual leaders, who arrive

dressed in ceremonial attire of traditional textiles, silver

breastplates and headdresses of feathers or silver horns. They open the

proceedings by chanting ritual verses, then take their places and share

betel-nut – a gesture symbolic of good relations all over South-East

Asia. The participants arrange themselves around the four sides of the

mat, with the CRP panel on one side, facing the community members, and

the deponents and victims to the panel’s left and right respectively.

The hearing requires a full admission and apology in the presence of the

community. The victim confronts the perpetrator, is entitled to

question them closely and must eventually say what will help them feel

better. Perpetrators must then undertake redress as directed.

While the success of truth commissions cannot be quantified,

international observers from all over the world have heralded East

Timor’s quasi-legal efforts as ground-breaking. Ultimately, the truth

commission exceeded its planned goal of hearing 1000 cases. By the end,

it had received a total of 1541 statements from deponents requesting to

participate.

Thus the modern truth commission is not bound by the Western legal

legacy – the words of Blackstone and Plato no longer play into the

mandate of transitional justice. Instead, what is the centerpiece of a

truth commission is the nation itself. The truth commission incorporates

and fuses community. By internalizing the unique facets of a conflict,

the truth commission can be molded into an institutional structure that

can provide for generations. Think not of the truth commission as some

sort of probe, an inflexible tool wielded by the West to humiliate the

developing world. Instead, the truth commission is a malleable mechanism

of empowerment, aimed at integrating into a nation and providing

something – whether it be truth, reconciliation, or respect – which has

yet to be provided through normal means.

Sri Lanka’s latest efforts to set up a TRC provides ample opportunity to

learn from other models. When Maithripala Sirisena surprisingly won the

presidency in 2015, ushering in a unity government with Ranil

Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister, Sri Lanka was poised to enter a new,

forward-looking era. It seemed possible that the myopic politics of

Mahinda Rajapaksa were a thing of the past. This hope was compounded by

Sri Lanka’s sponsoring of UN Human Rights Council Resolution 30/1, which

called for a credible judicial mechanism to investigate alleged human

rights abuses during the end of the civil war.

With the tabling of Resolution 30/1, the Sri Lankan government devised a

four part plan to ensure accountability: a truth commission,

reparations and missing persons offices, and, most importantly, an

independent special court for war crimes with international oversight.

Out of these four mechanisms, the government has publicly announced

progress in the Office on Missing Persons (OMP). The government has

promised that the truth commission will be launched by the end of the

year. The OMP still needs to be approved by Parliament.

During a recent visit to Sri Lanka, I met some of the talented and

passionate stakeholders working with the government to catalyze the

transitional justice process. It was clear that one of the most

important ways to accelerate the establishment of the TRC and to win

public support for it is to transform the way in which the local

communities perceive TRC. The key then is to focus on the political

messaging: framing transitional justice in a way that transcends

partisan politics, and positions it as a solution to larger problems of

national exceptionalism.

Last year, Foreign Minister Mangala Samarawera told the press that Sri

Lanka’s TRC was to be modeled after South Africa’s 1996 TRC. One

important lesson to be learnt from South Africa’s TRC is the way in

which it cultivated positive media attention. There are few transitional

justice efforts that have so effectively captured the national

imaginational as the South African TRC. Each and every step seemed

designed to make the biggest splash: from the appointment of

high-profile members like Archbishop Desmond Tutu to the regularly

televised broadcasts of “Truth Commission Special Report” each Sunday.

The political leaders behind South Africa’s TRC understood the necessity

of public support, and made a number of decisions to ensure media and

public engagement.

While the Sri Lankan government’s effort to adopt a flexible, home-grown

model used by more recent truth commissions will help to create a sense

of national ownership of the process, communicating a clear and

powerful narrative of transitional justice to the public will increase

its national credibility and international stature.

About the Author: Akshan de Alwis is the UN Correspondent for the Diplomatic Courier.

Jaffna GA's letters cause anger among uprooted Tamils from Valikaamam North

[TamilNet, Monday, 29 August 2016, 23:31 GMT]

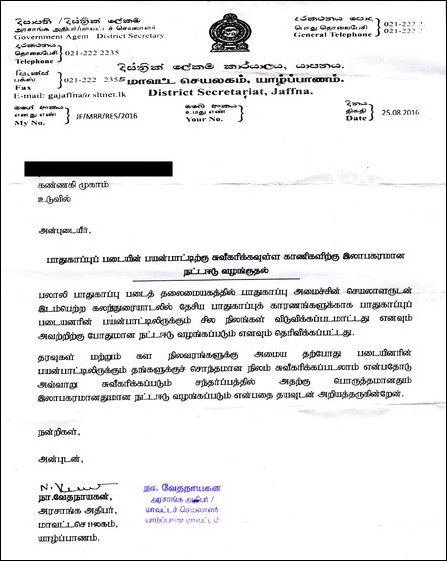

Occupying Colombo's Defence Ministry has instructed the SL Government Agent in Jaffna, Mr N. Vethanayagan to issue three different letters to the uprooted families in Valikaamam North, who are staying in the so-called welfare camps in Jaffna. A section of the people have been asked to prepare to move out of their camps and to accept alternative housing-scheme [being built by the occupying military]. Around 70 of the families staying at Sabapathipillai camp in Chunnaakam have received a second-type of letter that states that in the event their lands were to be permanently seized for military use, they would be compensated with ‘suitable’ and ‘lucrative’ alternatives. A third one asks the remaining to stay calm and wait for resettlement until the end of 2017. The letters have caused confusion and anger among the uprooted people who have been staying in the camps for more than 25 years.

The move indicates that the SL military is not prepared to release the fertile lands it has appropriated from the people of Valikaamam North, say the representatives of uprooted Tamils from Valikaamam North.

Informed sources at Jaffna District Secretariat told TamilNet that the GA was reluctant to issue such letters. But, he was instructed to do so after the insistance coming from Colombo after a ‘high-level’ decision made by the SL Defence Ministry and the SL President Maithiripala Sirisena.

Currently, 1,030 families uprooted from Valikaamam North are residing in 31 so-called welfare camps in Jaffna. Most of them are poverty-stricken.

There are more than 54,000 uprooted Tamils who reside outside these camps. They have not received any letters.

The SL Military is trying to exert pressure on the poverty stricken families residing in the camps to accept alternative solutions in order to permanently seize their villages.

Security Can Coexist With Human Rights

I felt sad to learn from the media that thousands who were displaced by

the civil war were still roughing it out in refugee camps, waiting for

their native lands to be released by the Army. According to the

newspapers thirty one welfare camps are situated in seven Divisional

Secretariats of the Jaffna District, housing 936 families, comprising

3,260 people.

The news took my memory back to 1997, when I visited the Poonthottam

Camp in Vavuniya, as the first chairman of the Resettlement and

Rehabilitation Authority of the North. It was a pitiable sight with

thousands of refugees from the Peninsula cramped in dingy enclosures.

Moved by their sad plight, I started transferring them back to Jaffna by

boat first through Trincomalee and then through Mannar as the west

coast became accessible. But some of the transferees could not be

settled in their own lands for security reasons, as neighbouring army

camps were exposed to attack by the LTTE. It is this residue that is

reported to be still suffering in makeshift digs that were then expected

to last only a few months. It is painful to reflect that toddlers that I

transported twenty years ago, have now grown up to adulthood but are

still living without a roof of their own over their heads.

To my mind this stagnation is a result of the clash of two interests.

One relates to security and the other to human rights. Understandably,

with bitter memories of the ravages caused by the LTTE insurrection, the

South gets worked up at the thought of reducing security camps in the

North, imagining from their armchairs that such a move would jeopardize

security, exposing the North to recapture by terrorist forces. In the

first place, terrorism in the North has been so much controlled on the

ground that its resurgence has become a far cry, as the Northern

Commander has declared recently. Secondly, there is enough crown lands

in the Peninsula to accommodate a perfect security regime without

compromising its legitimate objectives. On a recent trip through the

Peninsula, I noticed large stretches of abandoned land that was in use

when I was a Cadet in the Jaffna Kachcheri in 1957.

Geneva Resolution being implemented – Mangala

Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera on Monday assured that the the process implementing the Geneva Resolution was on track

Strongly denying a dispute within the ruling coalition over the process,

Minister Samaraweera stressed that President Maithripala Sirisena had

been consulted before the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) co-sponsored

the Resolution at the Sept/Oct, 2015 sessions of the UNHRC in Geneva.

The Matara District MP vowed to proceed with the process regardless of

resistance by hostile elements hell-bent on sabotaging the peace

initiative.

Foreign Minister Samaraweera Monday evening called a special session

with the media, including members of the Foreign Correspondents

Association to explain the measures taken by the government to address

accountability issues. Having explained the circumstances under which

the GoSL had reached agreement on Resolution 30/1, Minister Samaraweera

declared the agreement as Sri Lanka’s biggest achievement recently.

Minister Samaraweera revealed that at the time the issue had been taken

up at the Geneva-based United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), he

had been with President Maithripala Sirisena in New York. Foreign

Minister Samaraweera said that he had been able to obtain the

president’s advice, comfortably while Prime Minister Ranil

Wickremesinghe coordinated with Colombo-based diplomats involved in the

process.

Acknowledging the government’s failure to include a recommendation made

by the JVP relevant to the Office on Missing Persons (Establishment,

Administration and Discharge of Functions) Bill when it was presented to

parliament on Aug. 23, 2016, Minister Samaraweera said that it would be

accommodated to enable the process to go ahead.

Minister Samaraweera said that the Constitutional Council would soon

recommend to President Maithripala Sirisena seven members to the Office

of Missing Persons (OMP). In an obvious reference to recent media

reports pertaining to the appointment of Mano Tittawella as the

Secretary to the OMP, Minister Samaraweera insisted that a Secretary

hadn’t been appointed to the proposed office.

Declaring that the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe administration wouldn’t do

anything inimical to Sri Lanka’s interests, Minister Samaraweera

insisted that the Geneva Resolution co-sponsored by the GoSL wasn’t

meant to establish a hybrid court as propagated by various interested

parties. Responding to a query by the media, Minister Samarasinghe said

that foreign judges wouldn’t be included in the proposed judicial

mechanism under any circumstances though the GoSL could secure the

services of foreign experts. Minister Samaraweera said that hybrid

courts had been set up in some countries where the UN intervened.

Asked by The Island whether he could shed light on Jaffna District

Parliamentarian M.A. Sumanthiran on behalf of the Tamil National

Alliance (TNA) declaring in Washington on June 14, 2016 that Geneva

resolution 30/1 was subject to Sri Lanka agreeing to accommodate foreign

judges on a local judicial mechanism, Minister Samaraweera claimed that

he wasn’t aware of the said meeting. The Island pointed out that MP

Sumanthiran made the statement before the ‘Congressional Caucus for

Ethnic and Religious Freedom in Sri Lanka’ in the presence of Sri

Lanka’s Ambassador in Washington Prasad Kariyawasam.

Minister Samaraweera declined to indicate when the judicial mechanism would be ready or the members of the body.

Minister Samaraweera pointed out that the Paranagama Commission tasked

to inquire into accountability issues, too, received the backing for

foreign experts from several countries, including UK, Canada and

Australia. However, the GoSL was committed to ensure credible and

transparent process as requested by those affected by violence as well

as the international community.

Minister Samaraweera alleged that those who had accused the government

of betraying the war winning armed forces caused irreparable damage to

their reputation. Their relentless objections meant that they believed

the accusations directed at the military, therefore feared credible and

transparent investigations, Minister Samaraweera said.

Referring to varying figures mentioned by different parties, including

the ICRC in respect of the total number of disappearances reported

during the conflict, Minister Samaraweera said that the proposed OMP

would undertake a comprehensive inquiry in this regard. Emphasizing that

the country couldn’t further delay an inquiry, Minister Samaraweera

recalled how he teamed up with the then Opposition MP Mahinda Rajapaksa

during the second JVP inspired insurgency in the late 80s to represent

the interests of the families of the disappeared. "We set up Mothers’

Front to pursue inquiries into disappearances," Minister Samaraweera

said.

Samaraweera quoted MP Mahinda Rajapaksa as having said that he was ready

not only to take their cases to Geneva but go to Apaya (hell). Minister

Samaraweera said that now there was no requirement to go to hell as the

government had settled the issue. Inquiries could be conducted here,

Minister Samaraweera said.

The Minister alleged that the wartime Defence Secretary (Gotabhaya

Rajapaksa) had facilitated about 200 hardcore LTTE cadres to secretly

leave the country in the last week of the military offensive. The armed

forces brought the war to a successful conclusion on May 19, 2009.

In addition to the OMP and the proposed judicial mechanism, Samaraweera

also explained government efforts to finalise Draft Bill on the Truth

Commission by October and present it to parliament before the budget on

Nov. 10. "If we fail to do that, we will bring it to Parliament in

January.".

Enforced Disappearances: Curse in the Killings Field

Enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings continue unabated in Balochistan – Voice for Baloch Missing Persons (VBMP)

(August 30 , 2016, Balochistan, Sri Lanka Guardian) “The 30th of

August is marked internationally as Enforced Disappearance day but in

Balochistan, the blatant violation of human rights, extrajudicial

killings and enforced disappearances of Baloch are continuing at the

hands of the state agencies.” the statement issued by the VBMP has

noted.

(August 30 , 2016, Balochistan, Sri Lanka Guardian) “The 30th of

August is marked internationally as Enforced Disappearance day but in

Balochistan, the blatant violation of human rights, extrajudicial

killings and enforced disappearances of Baloch are continuing at the

hands of the state agencies.” the statement issued by the VBMP has

noted.

The state institutions and politicians justify their blatant human

rights violations under the pretence of Pakistani patriotism; despite

the obvious oppression and extreme deprivation imposed upon the Baloch

society by this state.

Balochistan’s home minister (Sarfraz Bugti) admitted that more than

13500 people have been arrested in Balochistan during a period of the

first half year; through National Action Plan. But state officials are

unable to provide details or whereabouts of the “arrested” people, even

the relatives of the victims are unaware of the fate of their forcibly

disappeared beloved.

The arrested people are often killed in staged encounters and are

falsely declared to be terrorists. On August 13, 2016, the dead bodies

of Gazain Baloch and Salman Qambrani were found dumped in Balochistan.

The last time they were seen alive was when they were arrested a year

earlier on July 7, 2015, at their residence situated on Qambrani Road in

Quetta. At that time, their relatives had gone to the area police

station to register First Information Report (FIR) regarding their

abducted loved ones. Although Gazain Baloch and Salman Qambrani were

picked up by state institutes along with Frontier Corps and other forces

in broad day light; before the eyes of hundreds of citizens. The police

outright refused to file the FIR. Then the aggrieved people contacted

the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP),

International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) and the Voice for Baloch

Missing Persons (VBMP) and registered details with them for assistance

in the safe recovery of the enforced disappeared Gazain Baloch and

Salman Qambrani. Sadly such examples exist abundantly in Balochistan.

The Voice for Baloch Missing Persons repeatedly received complaints by

effected families that torture is routinely used to coerce confessional

statements from the detainees. One such example is the confession

statements of Abdul Bari Nichari. The relatives of Abdul Bari Nichari

communicated that he was arrested by police on October 19, 2015, after a

quarrel with his cousins and put in lockup at a police station.

Afterwards, the involved parties resolved their conflicts and he was

released. Astonishingly, in a video aired by the provincial government,

Mr Nichari is seen confessing about a bomb blast in the local bus which

occurred on October 19, 2015. It’s absurd to think that a person who was

arrested on October 19, 2015, and in the custody of the police could

have detonated a bomb blast on a bus the same day.

This and other such incidents raise serious questions about the

transparency and authenticity of confessional statements extracted from

detained people by government officials. The organisation VBMP already

challenged the authenticity of confessional statements from detainees,

but now the evidence has validated those concerns. The organisation by

this time revealed that enforced disappeared people are charged in

fraudulent cases, and they are also being killed in fake encounters.

Most often their bodies show marks inflicted by extreme acts of torture.

Afterwards, the victims are falsely declared as terrorists. But the

state institute’s trickeries have been publicly exposed.

Regrettably, no government institute and the judiciary are intervening

in the ongoing inhuman activities in Balochistan, nor has the

international community given sufficient attentions to atrocities on

Baloch. Here in Balochistan, the media has also failed to fully portray

the real picture. Hence all these factors give the state forces full

impunity to commit human rights abuses and enforced disappearances.

The organisation Voice for Baloch Missing Persons often receives

complaints from victim families that they are being harassed by state

forces to withdraw from their struggle for safe recovery of enforced

disappeared persons. The organisation condemns the inhuman acts of

government institutes and demands for judicial rights and due legal

process for all including Baloch missing persons because the national

and international laws guarantee human rights to citizens without any

discrimination.

In the accordance of 30th August International Day for

Enforced Disappearance, the organization Voice for Baloch Missing

Persons (VBMP) once again invites attentions of political parties, human

rights organizations, the justice providing bodies and urges the

international community with United Nation to play their due role to

investigate the catastrophic human rights abuses in Balochistan and

reject Pakistan’s illegal practice of enforced disappearances.

Protest against disappearances

2016-08-30

2016-08-30

The Collective of kith and kin of those who went missing launched a protest at Liptons Circus today and demanded lasting measures to prevent incidents of disappearances. The protest was held to mark International Day of the Disappeared. Pix by Damith Wickramsinghe

The Collective of kith and kin of those who went missing launched a protest at Liptons Circus today and demanded lasting measures to prevent incidents of disappearances. The protest was held to mark International Day of the Disappeared. Pix by Damith Wickramsinghe

Searching for Answers: The Road to the OMP

Featured image courtesy VikalpaSL

RAISA WICKREMATUNGE on 08/30/2016

August 30 is the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances.

This year has seen the passage of legislation to enable the set-up of an

Office of Missing Persons (OMP). While the passage of the OMP Act is a

step forward in terms of transitional justice, it was a long and arduous

journey to get here.

There have been numerous Commissions set up in the past to investigate

into the missing, but the process has been beset with delays, and many

continue to wait for answers.

It was perhaps fitting that the Parliamentary debate leading to the OMP

Bill being passed was itself disrupted, with Foreign Minister

Samaraweera being surrounded by supporters in order to ensure that he

could finish giving his speech.

While setting up the OMP might seem like a positive step, there were

several pitfalls. Rights organisations have flagged the lack of public

consultations leading up to the Bill being presented in Parliament. As a

result there has been some mistrust on the part of the missing, who

have themselves come before many Commissions to present their story –

with little to no results.

There was also a deliberate campaign to block the passage of the Bill,

with former President Mahinda Rajapakse saying that those who supported

it would ‘betray the armed forces of the country.’ In an attempt to

counter the confusion and misinformation, Groundviews alsointerviewed several people on the consultation process, earlier in the month.

PRAGEETH EKNALIGODA ABDUCTION: MILITARY INTELLIGENCE INVOLVED – ASG

Additional Solicitor General (ASG) Sarath Jayamanne told the Supreme

Court (SC) that he had evidence to prove that Prageeth Ekneligoda was

abducted by intelligence officers of the military. Further he said that

he would take full responsibility for what he had said. Mr. Sarath

Jayamanne stated his position when providing answers to the petition

filed by the two intelligence officers now in custody in relation tot

the abduction on 29th Aug 2016.

This was reported by the Ceylon Today:

Jayamanne revealed this before Bench comprising Chief Justice Sripavan

and Justices Sisira Abrew and Upali Abeyratne, when providing answers to

the petition filed by the two intelligence officers now in custody.

The petitions had been filed by W.G. N. Upasena and Lance Corporal

Rupasena. The petitioners had alleged, in their petition, that they have

no connection with the Ekneligoda episode and they had been held in

custody without any reason for nearly a year, whereby their fundamental

rights had been violated.

When President’s Counsel Manoharan de Silva, who appeared on behalf of

the petitioners, made the submissions, the Additional Solicitor General

explained to Court thus: “The Police of Sri Lanka could not find a

single clue regarding the abduction of Ekneligoda, committed six years

ago. It is only after the change of the regime that it became possible.

“What a crime it is when it is comitted by the intelligence division,

which should instead be there to gather information to provide security

to this country. “Morali Sumedhiran had met Ekneligoda. He had an

identity card given by the LTTE. There was also a book with him with

phone numbers, which indicated that he surrendered to the forces after

the war. In that book there were phone numbers of very important persons

in this country.

“Ekneligoda owned a land at Habarana. Along with Morali, and

another individual, by the name of Nathan had gone in a three-wheeler

to that land to meet Ekneligoda. It is the petitioner who drove the

three-wheeler and on that occasion they have had discussions regarding

the politicos, when Pradeep had severely castigated the politicos. There

is recorded evidence of these, and those were recorded by the two

visitors to the land.

“After that incident, Morali had said that his brother Nathan was coming

to Colombo and had requested Ekneligoda to help him. These two

individuals who went to the Rajagiriya office of Ekneligoda, after

talking with Ekneligoda for a short while left the office along with

Ekneligoda. When they came out there was another group outside. They

blindfolded Ekneligoda and took him with them in a vehicle. He was taken

to the Girithale Army camp. There, Pradeep was shown photos of many

VIPs in the country and questioned.

“At that time Pradeep was in charge of the election campaign of Sarath

Fonseka who was a presidential candidate. Evidence has surfaced that the

cause of the abduction was a cartoon drawn by Pradeep,” the Additional

Solicitor General said.

Sarath Jayamanne along with Senior State Counsel Dileepa Peiris appeared on behalf of the Attroney General.

Sarath Jayamanne along with Senior State Counsel Dileepa Peiris appeared on behalf of the Attroney General.

Manoharan De Silva, PC, appeared on behalf of the petitioners.

Lawyers Sulakshana Senanayake, Hewamanne , Upul Kumaraperuma and senior

lawyer J.C. Weliamuna instructed by Sanjeewa Kaluarachi appeared on

behalf of Sandya Ekneligoda.

By Stanley Samarasinghe

President says no to break civil liberties of Muslims

One

security staff personnel, a head of a security force had brought in a

proposal at a crucial security staff meeting the other day to ban the

Muslim women wearing the ‘Burka”. To this proposal president Maithripala

Sirisena had not agreed.

This proposal had been brought forward with the clear intention to

prevent the ISIS Islam principles in cultivating roots for Islamic

terror. When the proposal was put forward the President had asked

whether there had been any clues identified in regard to this attempt.

However there had been only two instances of involving the “Burka” that

have been reported. One instance had been when a husband had come

disguised wearing a “Burka”while returning from the Katunayake

International airport to surprise his wife and the other instance was

when thieves had entered a bank in Kandy area to rob the bank.

The President had added that some European countries are making attempts

to ban the “Burka” but it cannot be allowed here as in such a

background like what had happened in the past era when the religious

conflicts and clashes took place, such repetition of events would take

place.

The President had emphasized that there no reports from the intelligence

services that ISIS terrorist organization is having links and is a

target in this country. Hence in these contexts there is no necessity to

raise alarms and in such a proposal to ban the “Burka” in this country.

However the President had stated that not to listen to certain

extremist persons in some organisations on this matter.

This view of the President was endorsed by the Prime Minister Ranil

Wickremasinghe and the Minister of Foreign Affairs Mangala Samaraweera.

“உதயன்“ மீதான தாக்குதலுக்கு டக்ளஸே பொறுப்பு! ஈ.பி.டி.பி .யின் உறுப்பினர் ஆதாரத்துடன் தெரிவிப்பு

உதயன் பத்திரிகை, தினமுரசு வாரமலரின் ஆசிரியர் அற்புதன் நடராஜன் மற்றும்

மகேஸ்வரி உட்பட யாழில் நடைபெற்ற முக்கிய கொலைகளுடன் ஈழ மக்கள்

ஜனநாயகட்சியின் தலைவர் டக்ளஸ் தேவானந்தா உள்ளிட்ட பல உறுப்பினர்கள்

சம்பந்தப்பட்டுள்ளதாக, ஈழ மக்கள் ஜனநாயக கட்சியின் நீண்டகால உறுப்பினர்

சு.பொன்னையா குறிப்பிட்டுள்ளார்

.

யாழ்.ஊடக அமையத்தில் இன்று (திங்கட்கிழமை) நடைபெற்ற பத்திரிகையாளர்

சந்திப்பின் போதே அவர் இவ்வாறு ஆதாரங்களுடன் குற்றச்சாட்டுக்களை

முன்வைத்தார். தொடர்ந்து குறிப்பிட்ட அவர்,

‘அரசாங்கத்துடன் இணைந்து வெள்ளைவான் கடத்தல் உள்ளிட்ட பல விடயங்களை

செய்தவர்கள் ஈழ மக்கள் ஜனநாயக கட்சியினரே. உதயன் பத்திரிகை தாக்குதலின்போது

அங்கு இருந்தேன். அந்த தாக்குதலை இராணுவத்தினரும் உடனிருந்தே செய்தார்கள்.

சாள்ஸ் என்பவேர வெள்ளை வான் கடத்தல்கள் உள்ளிட்ட பல கொலைகளுக்கு பிரதானமாக

இருந்தவர். நெடுந்தீவில் அரச உத்தியோகத்தர் நீக்கிலஸ் கொலைகள் பற்றியும்

பொலி ஸாருக்கு அறியப்படுத்தினேன். ஆனால், பொலிஸார் எந்த நடவடிக்கையும்

மேற்கொ ள்ள வில்லை.

ஊடகவியலாளர் நிமலராஜன் படுகொலை சம்பவத்துடன் தொடர்புடைய ஒரு சிலர்

யாழ்ப்பாணத்தில் தற்போதும் இருக்கின்றார்கள். சிலர் வெளிநாடுகளில்

இருக்கின்றார்கள். இந்த அரசாங்கம் கொலைச் சம்பவத்துடன் தொடர்படையவர்களை

கைதுசெய்தால், மேலும் உண்மைகளை அறிய முடியும்.

இந்த தாக்குதலின் போது காயமடைந்த ராஜன் மற்றும் திவாகரன் ஆகியோரை பலாலி

வைத்தியசாலையில் சிகிச்சைக்காக அனுமதித்தனர். அவர்கள் தற்போதும் உயிருடன்

இருக்கின்றார்கள். உதயன் பத்திரிகை மீது தாக்குதல் மேற்கொண்டவர்களும்,

தாக்குதலை தூண்டியவர்களும் யாழ்ப்பாணத்தில் தான் தற்போதும்

இருக்கின்றார்கள்.

நெல்லியடி, புங்குடுதீவு, காரைநகர், யாழ்ப்பாணம, வவுனியா உள்ளிட்ட

பகுதிகளில் நடைபெற்ற கொலைகள் மற்றும் வெள்ளைவான் கடத்தல்களுக்கு முக்கிய

காரணமானவர்கள் ஈழ மக்கள் ஜனநாயக கட்சியினர் தான்.

மகேஸ்வரி உட்பட தினமுரசு பத்திரிகையின் ஆசிரியர் அற்புதராஜா உள்ளிட்டவர்களை

தனிப்பட்ட காரணத்தின் ஊடாக கொலை செய்தார்களே தவிர, விடுதலைப் புலிகள் கொலை

செய்யவில்லை.

தாங்கள் செய்த கொலையினை விடுதலைப்புலிகள் செய்தார்கள் என விடுதலைப்புலிகள்

மீது குற்றத்தினை சாட்டினார்கள் என்றும் அவர் பல திடுக்கிடும் உண்மைகளை

ஊடகவியலளர்களுக்கு வெளிப்படுத்தினார்.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)